Crtd 15-11-06 Lastedit

20-12-27

Bert reads Einstein

Finding Special Relativity on Utrecht University Campus

|

This blog describes why I always wanted to study Special Relativity theory

and my personal practical vicissitudes in the 2 months I did it. For how since

this adventure and understanding it I explain the theory to myself see Bert

Reads Einstein [math] and [exercise].

|

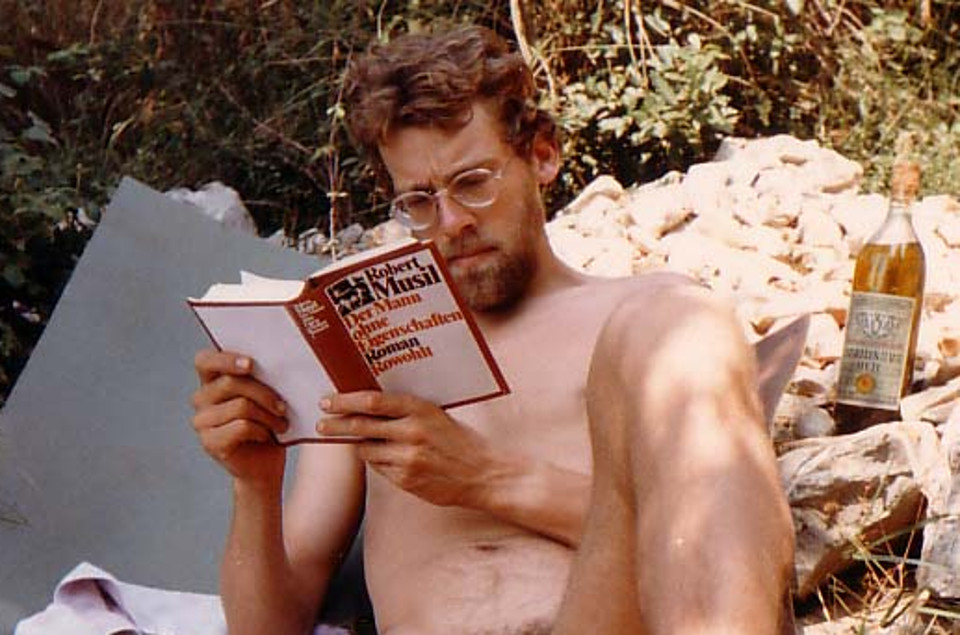

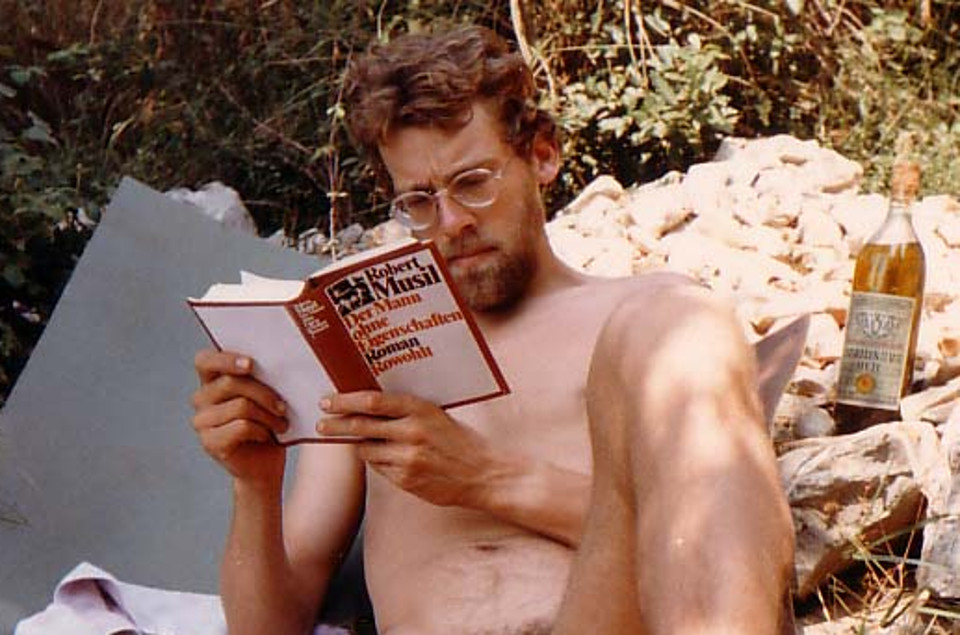

After recently finishing the part of Musil's Der Mann Ohne

Eigenschaften that I had set out to relate [see

my Musil relation], I

had promised myself to finally acquire understanding of relativity theory, probably

because Musil's protagonist Ulrich's last career disappointment had been

... mathematics! That was just a few days before the day where Musil's

book starts: for the first time a horse had had been called a "genius" in a newspaper

which had prompted Ulrich to abandon his highly promising university math post with

immediate effect. He was 32, very good at it, known in the literature for some

results. Though it is not mentioned, the profile Musil gave to Ulrich's

character leaves no doubt he studied and understood relativity theory: it was new

at the time, the entire educated public was aware of it, it

gets mentioned in Der Mann, and Ulrich was trained to read such stuff. But then came the

horse-genius. At the start of Musil's book,

Ulrich had lost his very last jealousy and

ambition and, now firmly aware of the ridiculous state of man, from small to

great, and his history, took time off to search back in Vienna for purpose,

albeit with a worryingly blank notebook.

Not me at the time I first read Der Mann (I was 31). I would need quite a bit more time

than Ulrich to loose my

social career ambitions.

In my early twenties while in my study in logic of scientific

theories, I had done some quick searches in relativity theory, for there it was often referred to in awe as the

best specimen of science, after which illustrations invariably got taken from

simpler theories like Newton's mechanics. Those were hard enough for me to

transfer to mathematical economics, where logical analysis of theory structure,

at the time, had only scarcely and crudely been exercised. I went into that.

In 1913, while Einstein was engaged in publishing his general

version of relativity theory while few yet had understood the previous, very

simple, first version, Mann-character top Austrian Imperial government

dignitary Graf Leinsdorf on a tense moment in the middle of the book shouts: "This psychoanalysis and relativity

theory or how you call all that crap, it bubbles up irresponsibly, and does not

care for the larger social consequences! ... we quickly knock something together

and before we even started to look whether it is something viable we are already

engaged with the next, or even missed the whole thing! A piggery!". Of course

these zillions of petty Freudian therapists setting out to cheat us for good

money indeed were all pigs, and I can't help

thinking of those cats and dogs of new

Microsoft Windows versions raining on us. And more.

His Serene Highness Count Leinsdorf sure had a point.

He led me again to aspire understanding relativity theory,

though a case in which the count's eruption

misses the point completely - and Musil no doubt was fully aware of that.

But I had no time: my head, in 1982, was

fully occupied with my dissertation that a year later caused, to my total surprise, a row

among the midget economics professors of Amsterdam University and then

got read by nobody, at least nobody serious - probably no reason for the world

to mourn, though it is excellent, original and could have helped the intelligent

mathematical economist to efficiently order his procedures - but I can't claim

that could have prevented a disaster, since there was none about to happen. I had gone

into it out of personal curiosity. No wonder the need for my results was not widely felt, though

in physics there was interest in this type of work, and even in the economic

academics of

the

years after quite some young talented successful career scholars joined the

fashion of what got called "economic methodology". However, they lacked the formal training to deal with my stuff, and

were not prepared to acquire it. A

career "methodologist" aspires to talk with academic economists, that's where money

and career are, not in founding a new obscure field for a new class of

insiders rarely deemed of interest by their research objects: mathematical

economists.

But I am still remembering with pleasure the making that analysis,

starting when 25

years old, with a university salary that I totally failed to consume, a 25%

teaching load and no publication pressure to threaten the quality of my work.

|

... my summer 1982

first reading (it looks I've just started!) of Musil's

Der Mann ohne

Eigenschaften (got into it through Wittgenstein's

Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus by Ulrich's contemporary Viennese Ludwig Wittgenstein

parts of whose personality strongly remind of Ulrich). Meanwhile I wrote my dissertation on dynamic logico-mathematical

analysis of economic theories (published as

Neoclassical Theory

Structure and Theory Development, Studies in Contemporary Economics, Vol. 4,

Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokyo: Springer Verlag, 1983 ...

|

The huge admiration in logic of science for

relativity theory surely

was caused by its overturning of a very admired and totally established

general

theory of physics, Newtonian mechanics, replacing it with something looking very

weird to the ordinary eye which nevertheless yields, in a simpler way, more accurate predictions

and descriptions of physical processes.

In the nineteenth century, the prediction and description problems

of Newtonian mechanics had increased with the increase in the number of ways and of

the accuracy by which one learned to measure not only body movements, but especially

electricity and light. A proliferation of imperspicuous

and unsatisfactory special laws and corrections to match theory with measurement

began to cause more and more headaches and frustrations among theoretical

physicists: physics was in danger to become an unordered toolbox of partly

irreconcilable theories!

Roughly the choices were to 1)

hope for piece by piece reduction of the chaos by harmonizing the worrying

amount of anomalies one by one, 2) to concede that our way to measure meters and seconds does

not result in the identical quantities for

every method of measuring physical processes, that is, to concede that

when meters and seconds in a system are measured from another system that

moves, they are meters and seconds of different lengths. This absurd

second option to straighten the growing mass of measurement "errors" out

(implying they were no errors after all) turned out, in the end, to win the

race.

First, as so often in such cases, the idea was proposed by a young

eccentric outsider who had tried but failed to find a

living in the academic world. After all, universities were originally

founded to maintain tradition, and even today do so, up into the wearing of those

ridiculous black guild suits of three centuries ago. Universities, the only

guilds left! We should be happy that this outsider

wrote a century ago, since nowadays it would have been hard to find people

willing to consider such a very strange and difficult solution of a puzzle. There

are so many of those fools with weird thoughts aren't there? And we have no more time nowadays to

read other people's thoughts: we have to publish!

Many influential career physicists opposed relativity theory so

vigorously that even 16 years after the start of relativity theory they managed

to have Einstein's Nobel prize ascription redrafted to exclude relativity theory

(an illustrative case of a guild-like network, as still regularly operative today, of

professors with more power and influence than brains - but already in the 17th

century Huygens (in Zedeprinten) and others complained of "gepromoveerde ezels" ("PhD donkeys"). They

still abound and did so at the time Einstein's ideas came out. But despite the extremely restrictive conditions of

the first version of relativity, these Heroic Defenders of the Traditional

Standards of the Guild lost the battle, due to overwhelming success of relativity in applying to many

cases with far less need for cumbersome special corrections to make things fit.

But, more spectacular, it yielded some

astronomical predictions totally alien to the Newton-type of thinking that got

dramatically corroborated and reached the world press. Soon,

relativity theory did

better in quite some applications than Newtonian mechanics in describing lots of processes involving

speeds in the order of the speed of light. Those are areas way off the public domain, only known to

specialist physics experimenters, and were even more so in Einstein's early

life, when mankind still predominantly relied on the power of the horse (in the first World

War 8 million horses died). In such everyday processes

relativity should be better than Newton as well, but

measurement in Einstein's days had by far not yet reached the precision required to measure the

difference, and once it finally started to do so, these differences were, usually, only of

interest to experts. But today, with cesium clocks, even time dilation during

ordinary long distance air flights shows.

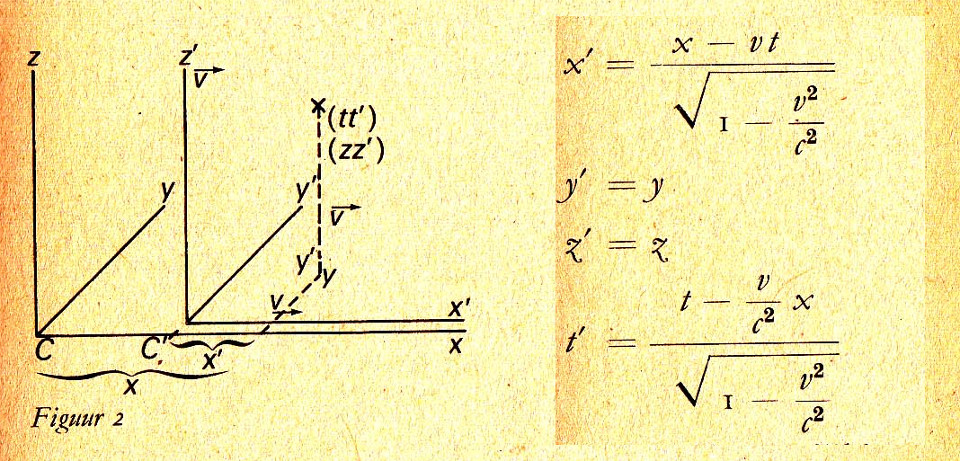

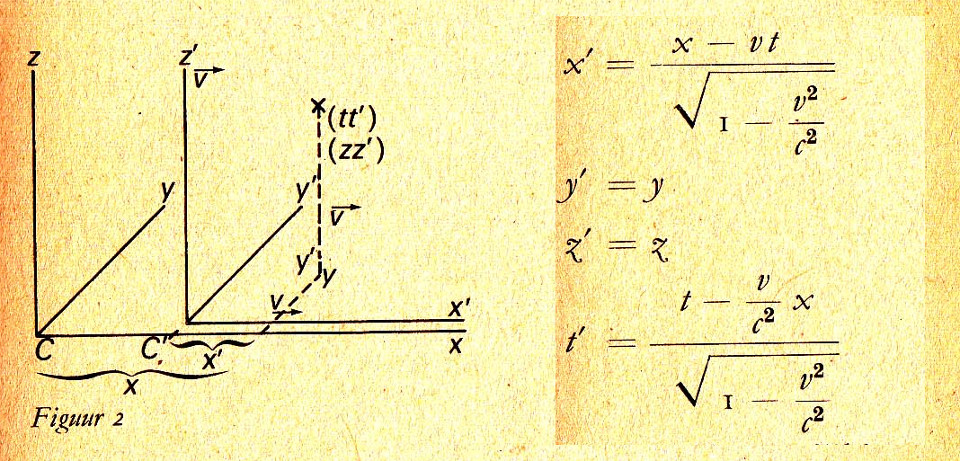

My good luck was to find an emeritus professor of physics in the

12footdinghy

racing competitions, so I could get some help collecting the literature and

solving problems. But I got no answer that enabled me to pass the graph below in a popular exposition

of relativity theory (Einstein, A.,

Uber die spezielle und die allgemeine Relativitätstheorie,

Braunschweig: Vieweg 1956). It is used to explain the fundamental Lorentz transformation.

The most simple case even. The math is easy, but I got

no clue whatsoever what he was talking about: space and time shift relative

to the objects moving around but the speed of light is assumed constant,

that is, the same if measured

from whatever object (planet, space vessel) moving with whatever speed in

whichever direction.

...

Lorentz-transformation. This was most of what Einstein needed for his first

(1905) revolution ...

... but what does it mean? ...

I did not see the light, literally: I failed to see how light was meant to move

through this graph. I might need a real teacher.

Help!

Utrecht University is a twenty minutes drive from my

Linge

river shore site. Its web site turned out to be, excuse me, a bit

of a disaster. Paddling around a

home page that was aggressively trying to divert my attention to a "virtual sleeping coach" and an

"anti-teasing program", in the end I found a course

name "mechanics", but could not find the address of the offices of the

physics staff, nor the material to be studied, the lecture rooms and times of service.

I took my car to head for the "Uithof".

At the entrance of the large university campus a signpost encouraged me to

navigate on the name of the street I wish to reach. A bit discouraging for I had

come in search of it.

"Physics"? To the university security officer engaged in writing number plates of illegally parked cars

that word

did not ring a bell, but he gave me a quarter of compass that held, in his

opinion, an above-average chance.

I managed to park. Legally. Took my foldable bike, entered a building. Its signpost featured the building's name,

that of a person, not related, as far as I know, to any academic field. It did

not list or say

what was inside. An exiting student apologized for not knowing

the whereabouts of physics: he was in informatics. The muscular Arabic receptionist's face made clear that both the term "physics" and the

word "department" needed more explanation (where in the latter case I made no

progress trying the word "faculty").

"Well you know", the muscular Arabic receptionist told me, "This is the beta

building".

"That's not so bad at all", I was delighted to reply "physics is pretty beta.

Is there any staff up here?"

"Staff ...", the man repeated with some

hesitation.

"I mean the office rooms of the people who teach here".

"Oh

yes, cross the hall and go up".

... I thought those would be two different institutes ...

Behind this door, I expected to find two

entirely different institutes, for 17th century Spinoza, though a renowned grinder of very

good lenses, simply copied his physics from Descartes (while at the time Newton recently

had become available in Holland). I simply could not believe somebody would name

a physics institute after Spinoza, of all people. In Spinoza's Cartesian view

the universe is totally filled

with a dust of very fine particles. There is no gravity. Dust particles push each other

round to

form kind of twisters, small and big. Those dust particles, Descartes held, pushed the planets round en kept pushing

us against

the earth's surface. I studied Spinoza's take of this in his Ethica

while making the now widely used Spinoza Ethica Help Web.

[my vicissitudes while making: Spinoza].

... trotting up: police arrest wing colours and hardware ...

... blue darkness, blind doors ...

... Top floor: only the Spinoza Instituut, where's Theoretical Physics

Institute? ...

Behind that door I suddenly was in a bright comfortable top floor

unit with lots of roof light. A top research institute in ... physics. Spacy

light rooms. In some, people were typing, in others two or three were

talking matrices, tensors, equilibria and filling wallboards with wide

gestures. One thing was clear: if I would be given a desk here and allowed to

ask any question arising while studying relativity, I would be done in a few

days. The other: I did not belong here. These guys and girls were too good. All

around thirty, no

Dutch people either, except for the manager who kindly named

the building

to me where they know all about bachelor teaching.

Thank you.

Would not want to have missed this short digression.

... Homing in on target, my foldable bike did not mind me to stay away long ...

The "Buys Ballot" building was surrounded by bicycles! I

told reception

staff there was a physics course I could not find. They tried, did not find, but knew the room number of Els, the planner of

physics courses. Els gave me all data of my mechanics course, and an efficient staff web

address (not linked to from the university's home page) to

find those data next time.

... reception knew Els' room, she helped me out ...

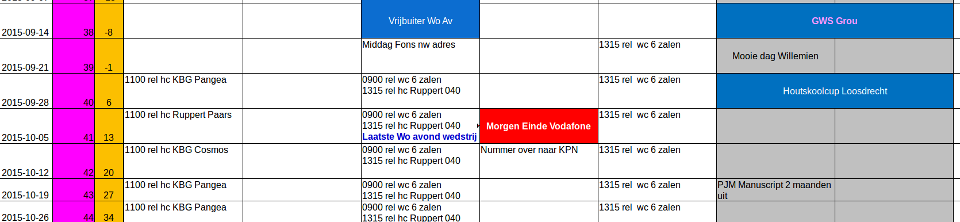

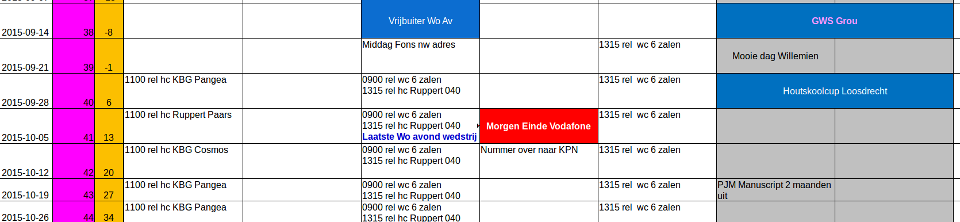

Not long after I had returned home, my schedule sported signs it had not

seen for 16 years (though blue is

12footdinghy competition sailing):

... Last

time my schedule sported this type of shit was December 1999 (but then even

worse: as a lecturer) ...

They had already started some weeks ago, but classical mechanics

(Newton, Kepler) had been done as well, most of which should be familiar to me.

So, the next Monday morning my alarm clock unchained me, I arrived

early, students told me what books and what lecture notes were used, and what is

the floor and room

number of the physics student's association that sells them.

... this is serious!

...

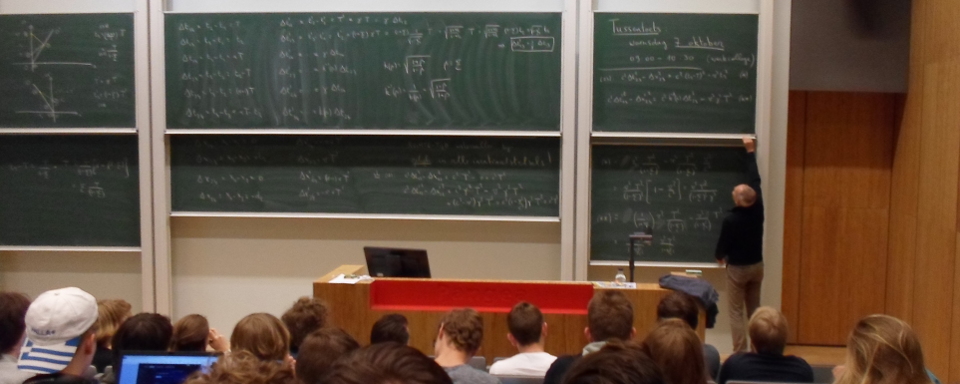

There I sat, taking chalkboard shots every one of which seemed to

require hours of work at home. Students are updated by a digital "blackboard"

(forcing me to rename the analogue one to "chalkboard", but that's a better

label anyway). For the digital "blackboard" you need a login, the end

of the university as a public institution, we are now just another commercial

shop. Well, no need. By now I should have enough. The login

protected digital blackboard made me realize why my search for my target had been a bit

erratic: I had accidentally taken an unused inroad over a campus security

officer, muscular Arab receptionist, Spinoza and Els. Thus

circumventing the

university's web welcoming page's "virtual sleeping coach" and "anti-teasing

program", I inadvertently managed to squeeze my rather

oversized body

through an unmonetized mouse hole entrance of the theatre! I saved a value of at least some sizeable boxes of excellent Cuban

cigars,

very agreeable smoking while, as I would soon start to do, covering paper with math.

150 audience or so. Astronomy and physics bachelors. Among these 17 and 18 year olds there were quite some Asians.

But a surprising lot of Arabic and

Turkish students, native speakers of what unlike Dutch are world languages

(Arabic 300x106 speakers, Turkish 200x106, until deep in

Siberia and China). These

brightest children of what the Dutch call "backward quarters" abound

all over the university's beta quarter - good idea: if you learn

something too difficult for others you can't be discriminated against. Let the

Dutch youth study "management" whatever that may be. But everybody

there perfectly understands the Dutch of Flemish teacher Professor Stefan Vandoren,

engaged in translating the English lecture notes of his predecessor De

Wit back into real Dutch. I saw De Wit's English version of the lecture notes in

some student's hands.

Ok. Dutch. Our midget German dialect on exit,

as some say? Dutch physics terms are sometimes badly chosen and

confusing: impulse is called "stoot", momentum is called "impuls", they

also use the word "moment". It means torque.

They use "dilation" and "dilatation" in a random mix. A murky mess, like Dutch

language generally, historically indeed pidginized German.

Dutch physics at first had nothing to do with it for it proceeded in Latin. The problem arose when deep in the 18th century

The Netherlands got in unbelievable decay, chickens and their shit all over the

place, Latin started to wane at Dutch universities

and nitwit physics professors on hunger wages started to copy physics from Latin into Dutch language.

That was the period in which foreigners started to say "in

The Netherlands everything happens 50 years later". But

today the Rhine wetlands are

catching up again: surely fifty years from now under the management of our

immigrated talent, we shall be top of the heap and Dutch language will be

in the league of Frisian and Lower Saxon (=Plattdutch, a pidgin German rival of

Dutch but spoken from Groningen all over Northern Germany to Riga, 76x106

speakers): abolished for all serious purposes (how's that from me, I'm half Frisian, half

Lower Saxon).

But where was I? O yes:

so, I longed for De Wit's English, but, ... not sold anymore by the

students association, only on the "blackboard". OK shit happens.

By far most

students were white and

Dutch, clearly from all strata of society: here selection had been on brains

only! What a relief hearing all these youngsters talking functions and equations in the

intermission instead of the ordinary adolescent Facebook bullshit.

The week after, also an African young man

joined and sat next to me. By way of

test, I pretended not to understand a fairly simply thing and asked him.

After a silence of a length that made my sweat break out he said:

"... yes I also found that a bit odd ..."

I: "Well, I believe it is correct, I just do not understand why"

He: "Yes, I'll have to look at that too".

Not the surprise I hoped for (I live in Africa now for 12 years

[more] and

have closely worked, often as the only white, in

groups of Africans on many different issues from

language analysis to

shipbuilding).

I asked the fat rosy white acne ridden highly +-dioptric adolescent at my

other side who swiftly produced the explanation.

I turned to my black neighbour

again: "Have you heard?"

He hadn't. Managed to wheedle a scholarship off a European philanthropist?

That's what they're damned good at ... anyway, postman soon.

Professor Vandoren is an entertaining

teacher. He is not copying

a sheet of formulas on the chalkboard but starts calculating

right in front of us.

Live calculation! As a jazz player [more] I know how you enhance your

connection to band and public by NOT putting a score

sheet in front of you, here it was the same! And more: when

you make a truly live mistake there is no disappointment. It shows how difficult

the subject is you are about to master! A mistake,

especially one that blocks the proper outcome and leads to Vandoren taking distance

from the blackboard, silence, hand at chin in frantic

scanning of the rows of symbols, sends a

shivering through the smart part of the audience. Then someone sets out to help

him. But he's wrong. "No that cannot be the error", Vandoren explains calmly "because if you look

here, these two ..." Now the crowd is at peak concentration! Another student

discovers somewhere a c2 copied to c1.

As for intensive

and successful teaching, nothing works better than the tension of an error on

the chalkboard.

Vandoren looks, corrects, looks back, laughs and says. "Sharp!".

Looks back to the board and back to the student, says again: "Very sharp".

Lesson #1 to

the freshman and -woman:

there is never need for shame.

At another calculation derailment Vandoren judged he was loosing too much time

"... I think I did not go the easiest way ... anyway you should be able to do

this at home ...", looks again to the blackboard, clearly nervous, finds the

error, quickly writes the result and says, with a shy smile: "... yes when everybody is

looking at you, it sometimes is less easy to get out ...".

Important lesson #2:

you may feel shy, but you don't give up!

How's that for a teacher! Never seen that! I myself know that

situation when lecturing, but never could smile getting in and out of

trouble on the blackboard - excuse me chalkboard. Now I have Vandoren's example, I could do it but fortunately

my savings made my sentence to academic teaching expire long ago.

Home with the 4 euro 23 cents or so Flemish teaching doc "Special

Relativity Theory" and a fairly cheap thick English physics text book bought in the physics student's association room.

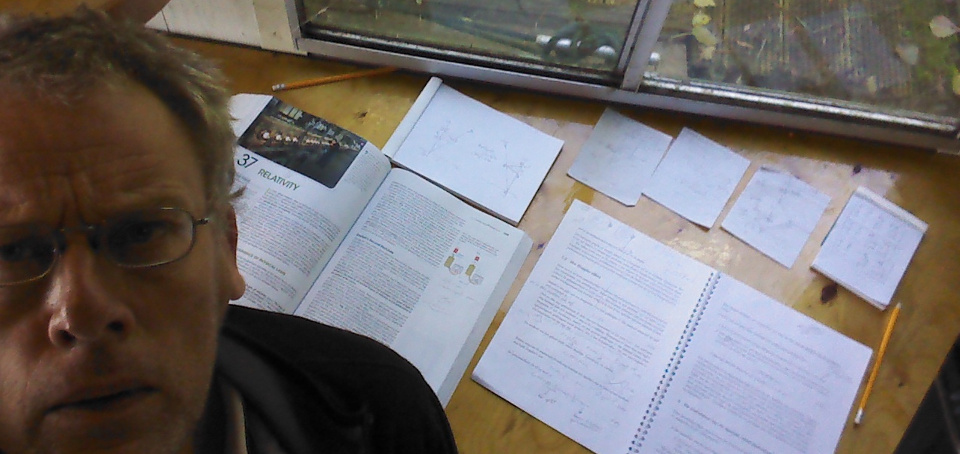

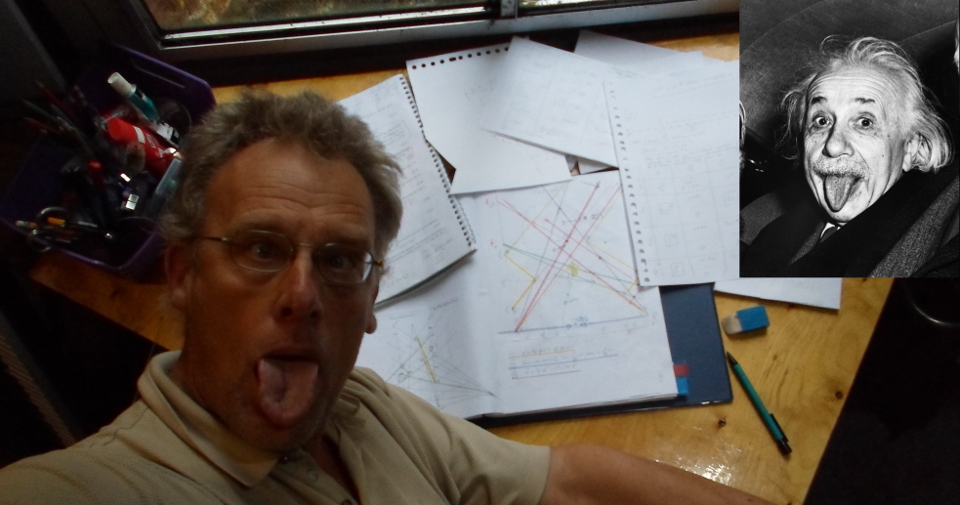

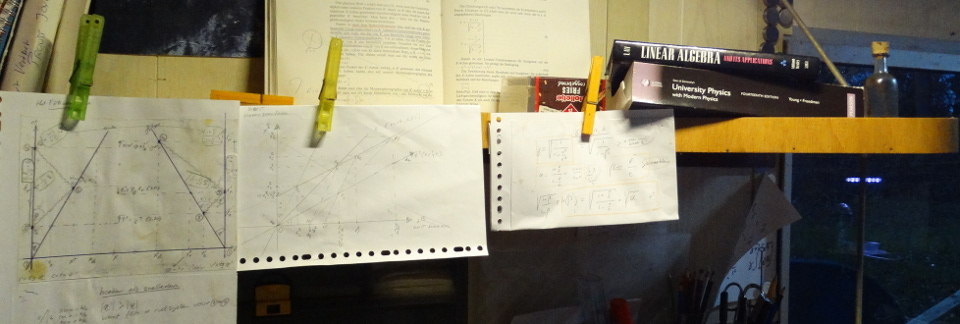

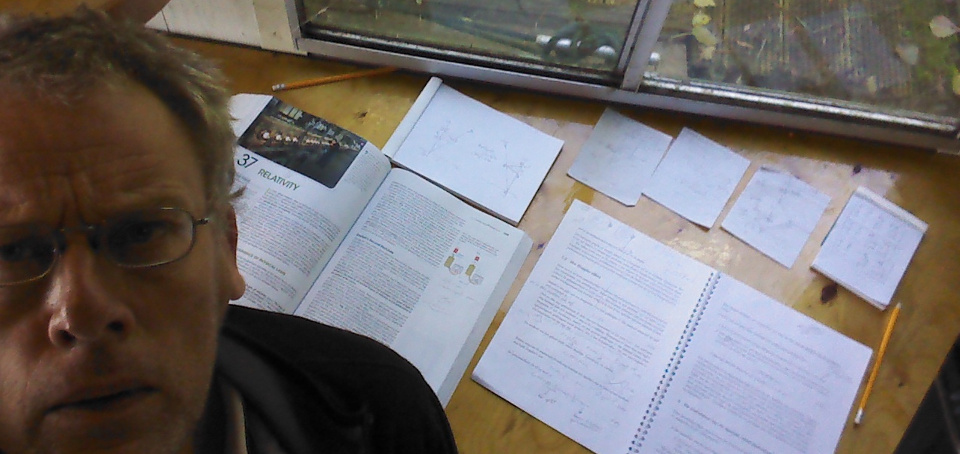

... Back to my heavenly solitary

riverside home with the teaching docs ...

... On

September 28, 2015, I starting filling my dustbin with math-covered paper ...

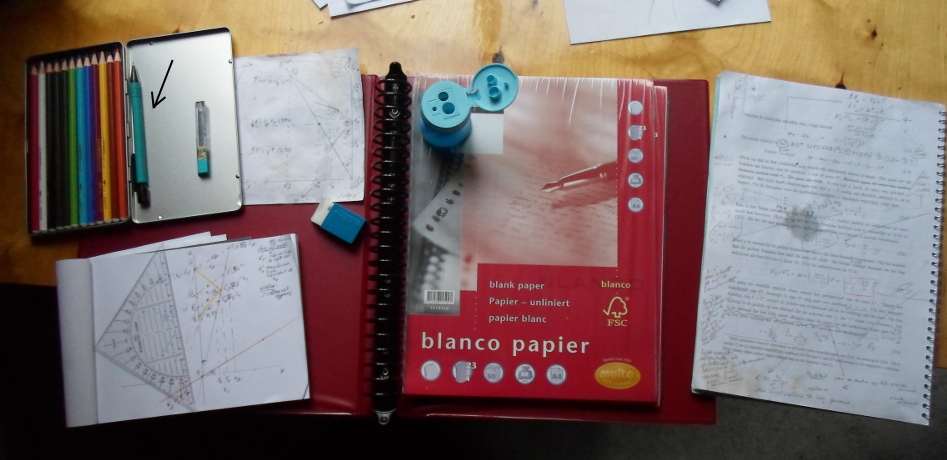

... my old habits revived: non-digital hardware use ...

Since I last used non digital studying hardware twenty years ago (I lost my

last books and paper notes in a

tornado on Lake Victoria, without much regret: after all it's all on internet now) the quality of colour

pencils has

risen, clickable ring binder handling has become even more comfortable, pencil sharpeners

have further improved, geo-triangles are thinner and more flexible and there still

is replacement filling for my beloved graphite pencil (left at arrow) I

kept on me for over 15 years living in the

Alps, Africa, and wandering with my

Kangoo microcamper from

Inverness to

Marrakech.

After some weeks of Utrecht lectures my despair, frustration and agitation all

peaked. Little did I know, immersed as I was in trying to follow the Utrecht version of the

relativity story, that what Vandoren told on the

very first lecture already implied that Einstein's pen made a small slip

where he wrote in Anhang 1, to explain that graph reproduced above : "längs der negative X-Achse sich

fortplantzenden Lichtstralen", while he clearly means "sich in negative

Richting fortplantzenden Lichtstralen" (which can be along the positive x-axis

too!). If he had

written the latter, which clearly is what he had in mind - it's just a

slip, no wonder when you have explained it a thousand times - I would never have

considered to go to those Utrecht physics lectures.

Another proof of my observation above that nothing boosts progress more than errors. Thank you Einstein! No way to sniff out that slip when

you do a first

relativity theory reading, like I did. And when the stuff to sniff it out came along in Utrecht,

I failed to notice, since I had laid

Einstein's booklet aside in utter disappointment after even checking the Dutch

translation, which had literally copied the slip ("lichtstralen

die zich langs de negatieve x-as voortplanten"). So I thought: this looks crap

but he's serious, so

I need a live teacher.

In the meantime the Utrecht exposition had

begun to firmly blur my brains on other unrelated issues ... How long would it

take before I would get the idea to turn back to Einstein's little book and see

that Vandoren in the first 10 minutes I heard

him had given the stuff needed to understand what had blocked me in Einstein's

derivation of the Lorentz

transformation en read on from there?

Clearly, since its appearance 1956, nobody can have understood the Lorentz transformation from Einstein's

little book or its Dutch translation except those who somehow understood this

"negative X-Achse"-thing was

a slip of our hero's

pen (details).

...

Brain-blurring physical reasoning ... Help! This guy is CRAZY!!! ...

In those weeks of desperate and frustrated search I noticed myself starting cooling my rage on ordering everything else

around me! Ridiculous,

but I could not stop myself.

... cooling rage on

hardware order ...

First the pencil box, then the rest of the shelf where it stands (up-left in

picture), then the

opposite shelf with its hardware boxes (up-right), then an ergonomic lighter

suspension (down left,) then my coffee making system (down middle), finally

introducing a pill box to put 7 of my one-a-day pills on Monday and

sync day-awareness with that of whether I took my pill ... all to no avail of course:

the shit was in my brains.

And

I had headaches. Literally. I NEVER have headaches.

... Finally it was Einstein (middle) who made me understand the Lorentz transformation ...

It took three weeks of filling my dustbin with papers full of graph and formula

trials. But then, on October 22, 2015, after almost a full month of

wandering through a dense forest in circles, I was desperate enough to

draw Einstein's little book from the shelf again. Only then I realized that Vandoren's

take implied this "negative Achse"-thing should be a

slip, could I read on. In Einstein. That same afternoon I understood

the Lorentz transformation.

I wrote it down too in Bert

Reads Einstein [math] and [exercise]. There,

unlike Vandoren-De Wit, I first completely prepare the Lorentz

gymnastics-floor following Einstein's exposition [math] , After that is clear, Vandoren's illustrative

examples and exercises are of great help to turn your first successful relativity

moves into a smooth vegetative routine of relative time and distance measurement.

Acquiring that is more like coming home with a

new scale for your musical instrument en start playing it. Sounds rusty at first

and will take weeks of daily exercise

to get smoother. It did: [exercise].

Meanwhile I had spent roughly the equivalent of a reasonable tuition fee on

Cuban cigars, and shall have to gear down the addiction by means of a week of

abstinentia.

Last

but not least, when proudly reporting my results to my friend Ben (left),

retired nerd, of my age, my physics, especially electronics teacher when we were

in our fourties, now living in a Turkish mountain village with lots of cats and

an amazing experimental transmitter, turned out to disagree with Einstein about

the very nature of radiation. I had good practise trying to defend Einstein. We

are still in disagreement, though I always thought I could explain everything to

everybody once I understand it myself. But no! By way of hommage to Ben, amazed

finding him unimpressed by the rather overwhelming power of Einstein's

reasoning, I published his view on a separate page:.

Last

but not least, when proudly reporting my results to my friend Ben (left),

retired nerd, of my age, my physics, especially electronics teacher when we were

in our fourties, now living in a Turkish mountain village with lots of cats and

an amazing experimental transmitter, turned out to disagree with Einstein about

the very nature of radiation. I had good practise trying to defend Einstein. We

are still in disagreement, though I always thought I could explain everything to

everybody once I understand it myself. But no! By way of hommage to Ben, amazed

finding him unimpressed by the rather overwhelming power of Einstein's

reasoning, I published his view on a separate page:.

Last

but not least, when proudly reporting my results to my friend Ben (left),

retired nerd, of my age, my physics, especially electronics teacher when we were

in our fourties, now living in a Turkish mountain village with lots of cats and

an amazing experimental transmitter, turned out to disagree with Einstein about

the very nature of radiation. I had good practise trying to defend Einstein. We

are still in disagreement, though I always thought I could explain everything to

everybody once I understand it myself. But no! By way of hommage to Ben, amazed

finding him unimpressed by the rather overwhelming power of Einstein's

reasoning, I published his view on a separate page:.

Last

but not least, when proudly reporting my results to my friend Ben (left),

retired nerd, of my age, my physics, especially electronics teacher when we were

in our fourties, now living in a Turkish mountain village with lots of cats and

an amazing experimental transmitter, turned out to disagree with Einstein about

the very nature of radiation. I had good practise trying to defend Einstein. We

are still in disagreement, though I always thought I could explain everything to

everybody once I understand it myself. But no! By way of hommage to Ben, amazed

finding him unimpressed by the rather overwhelming power of Einstein's

reasoning, I published his view on a separate page:.