Crtd 15-03-10 Lastedit

20-12-27

download pdf

Post

to order free paper booklet

Robert Musil

Der

Mann Ohne Eigenschaften

First Book, Chapter 1-74

FIRST PART

___

A KIND OF INTRODUCTION

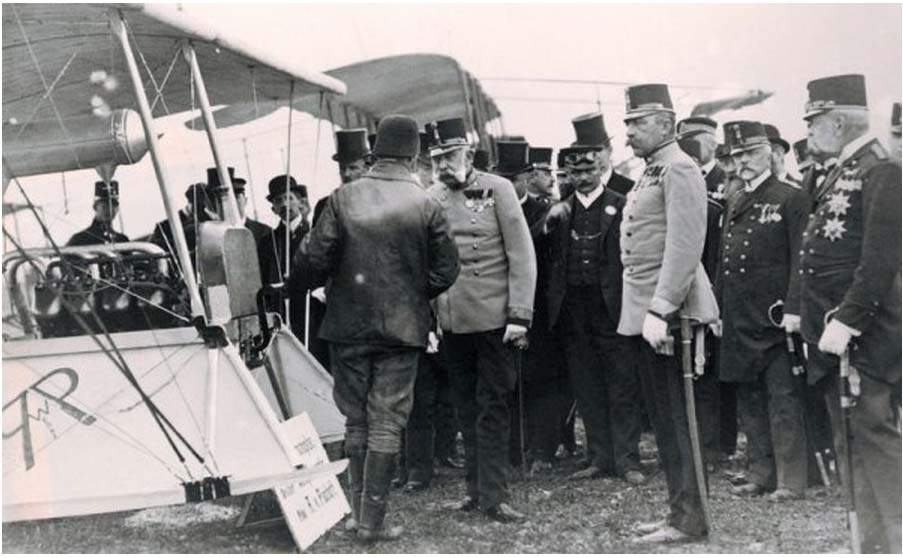

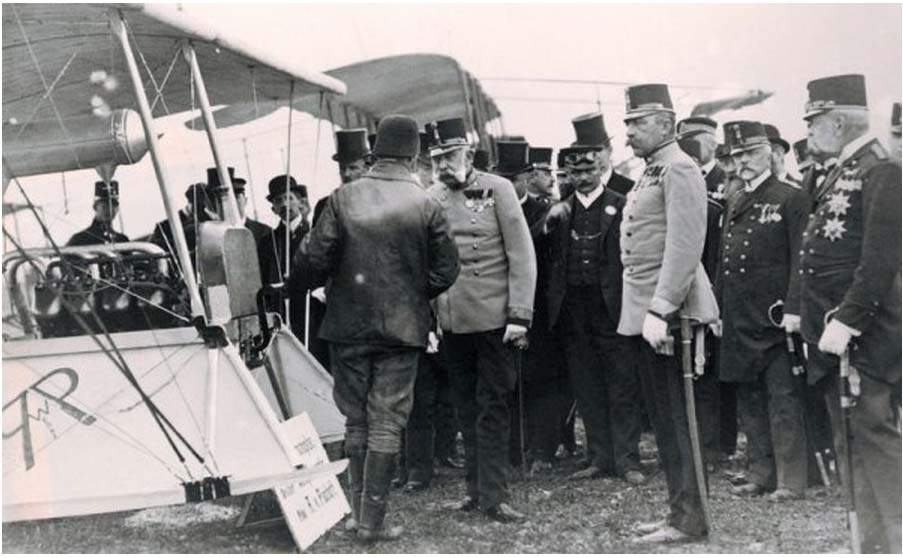

... Franz Josef, emperor, king and supreme commander of the Austrian

Hungarian Monarchy, speaking to an aviator ...

...

the awareness that the progress of our understanding of nature from the times

we ran after rabbits with clubs of wood until the moment we took the air

would fit in a moderately sized private library, whereas all religion,

philosophy, morality, patriotism and the like neatly stacked side by side

would span the entire earth, while yet the larger part of it was not

communicated through books but through stakes, sabres and bullets ...

(Chapter 61)

- I -

1. Some things going, remarkably, without consequences.

Though when our nose is a bit red we could not care less about the

exact wavelength of its particular colour, we always seem to be adamant in

wishing to know exactly where we are. Well, this is, in august 1913, Vienna, the capital

of the Imperial-Royal Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy. All around us, in this

traffic artery, objects and people move along each other in complicated streams,

and no one is in any doubt that this will remain for ever - though we now know it

would stay in existence for only 63 months more. A huge tangle of carts, horses, trams,

pedestrians and even cars and motorbikes.

Closer inspection reveals that a truck just stopped at the

side of a man who lies, motionless, on the pavement. People approach like bees

at their hive. The driver's widely moving stretched arms suggest desperation and

innocence.

An elegant couple, clearly of a standing warranting personalized

wash marks sewn into their underwear by their staff, approaches as

well. The woman senses an uncomfortable feeling in her stomach that indicates

compassion. The man comes to her rescue by telling her he saw the victim moving

a little when it got lifted into the ambulance. To take no chances, he adds some

technical remarks about brake paths and traffic statistics, thus giving the woman

the impression that the accident is, outside her horizon, firmly under

control, as really, by the orderly way it took place, it seemed like having

happened under regulatory orders of the local authorities.

4 If there is a sense for reality, there must be a sense for

possibility.

The general belief in the existence of a sense for reality endowing

blessed people with "realism" especially shows itself where

head-shaking people discuss others unfortunately less blessed with it. This type of

head-shaking is consistently observed if a case is discussed where someone -

rarely indeed the speaker himself - fails

to reach his objectives by choosing methods inspired by sheer phantasies based

on hope or desperation. If it, I mean this sense for reality, really exists - and that

is rarely denied - then there must be a sense for possibility as well, by which

one is aware of reality, but only as a part of all possibilities that

can realize themselves, others among which might do so tomorrow,

or even might have done so already at another place.

Someone endowed with a sense for possibility sees reality though,

but he is not limited by it for he sees it only as one of those many

possibilities, the one that accidentally realized. And if your talents stretch

that far you might go all the way to consider what qualities you could

possibly have had. And if you consider that well, you might, in the end, as a

thinker about all those possible qualities, feel like you have none whatsoever.

And this book is about such a man. His name is Ulrich, he was 32

when this book starts, and mathematician (though, yes, all of this could have

been totally different). Ulrich had just returned to Vienna from abroad to

find out if he could fill a gap in himself: he had no roots. He was pretty sure

of that since he had learned to find the roots even of very difficult systems of

equations - if they had any, which not always is

the case, and now he had found

he fell in that latter class.

So he rented a shabby little castle, swallowed by the suburbs of

Vienna, started to make and dispose of a lot of sketches for futuristic

furniture, then decided to leave it to the taste of the suppliers in order to

give way to tradition and thus have a good look at it within his own home, all

this at the expense of his father, a wealthy, successful and influential lawyer

- who, by the way, as a bourgeois with a lot of clients in the nobility, thought

of this funny castle as slightly inappropriate.

After which he went living there and started to receive the

girlfriend that in the meantime he had met, Leona, a properly shaped cabaret

singer with a good appetite and a healthy commercial sense of carnal pleasures.

One evening he came home rather bruised and bleeding, deprived of

the objects of value he had on him. Pondering how the disparities and forces of

human society naturally tend to equilibrium, and having just been involved in

some of that dynamism, what technical errors he had made (1. too slow, been in

thoughts, 2. in counterattack started with the wrong adversary, 3. counterattack

not surprising enough by failing to mimic fear) he checked his injuries which

turned out not serious.

After dwelling on the vanity of individual heroism in the light of

the relevant social laws of reaction, it dawned again on him that next to his

body, stretched on the street, an automobile had stopped, the driver of which

had tried to lift him at the shoulders, after which a lady with a angel-like

gaze had bent herself over him. On her question whether she could bring him

somewhere for first aid he had given the address of his castle. On the way there

his brains had started to function again and he had given the motherly sensual,

warm being next to him, of roughly his age, a deeply carving lecture about body

and mind in the martial arts, with some appendices concerning related

philosophical subjects.

When dropped he failed to get her address. Now the next morning,

while with some relief he realized that had protected him from another vain

adventure, she reported at his door, heavily veiled, and they became lovers.

Bonadea. That was her name. She turned out married, upper class,

endowed with elevated morality, but charged with an uncontrollable sensuality

for which she had created an underworld hermetically closed off from the rest of

her life, in which she had worn out a lot of men - or the other way around.

Then Kakania, the Imperial-Royal Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy, an

oiled bureaucracy that granted the citizen as much freedom as possible, under the

patronizing leadership of a noble political elite. They cunningly exercised the

tough job of governing a huge realm containing palm trees, glaciers, palaces

and clay huts, where everybody had nine identities at least: an ethnical, a

geographical, gender-, class- and professional identity, conscious and

subconscious identity, and finally everybody had its own private one in reserve.

Those little waters streamed, intertwined, merged, split, but failed to reach

every part of the estuary, so there were dry places. And this triggered a tenth

identity: the way your mind formed ideas about those unfilled spaces and what

could be done with them.

So is it everywhere, of course, but in Kakania it was all still a little bit smaller, a little bit less extreme, less feverish than in the other

big cities of civilization.

9. Attempts to become a man of significance.

Already three times Ulrich had made the attempt to become a man of

significance. The first time, out of admiration for Napoleon, he had registered

as reserve officer cadet in a horse regiment. There he soon discovered that his

choice of profession would not bring what had inspired him. He left the service

to learn the heroic trade of a technical engineer, who, with macho gaze and a

pipe, sports cap and elegant horse boots travels between Cape Town and Canada in

order to execute the daring designs of his company. But then his first

colleagues turned out not to appeal to his imagination in being quite satisfied

in the small jogtrot of their uneventful lives, easy-going curved backs

grown around their design tables showing no sign of any frustration that the

glory of their technical capability had failed to reach their souls.

Ulrich still thought his third attempt not too bad: mathematics,

the foundation of science, of the feverish activity of the ever larger ant hills

of people all around the world, not like the dead principle of a machine made by

one of those design-table zombies who had memorized some rules without

understanding, no! Alive, in your own brains!

He still liked it because he had thus far failed to realize that

science would be unable to replace the old fashioned human soul, that the

resultant of the two forces would lead smoothly to poison gases and bomber

planes, and that mathematicians are totally unaware of this since they are, like

racing cyclists, peddling industriously, looking at the rear tyre of the man in

front of them.

He admired math and science as a revolutionary alternative

(to the thinking of the past, God, family, fatherland, obedience, discipline

etc.). As a permanent revolution even, for science kept putting itself upside

down and thus regularly gave another boost to knowledge and technique.

This bizarre motivation had been unable to prevent him booking some

results.

A "man of significance". Even that third time he had tried to

become one, and acquired the status of "hope". "Talent", surely, "genius" maybe.

But then came a dramatic moment in which he fell at odds with his own very

purpose: newspapers started to write about authors and tenors as "geniuses", and when

that shelf got full, mid halfs and boxers appeared. But Ulrich finally

broke when the first horse was reported to be a genius. He had left his horse regiment

in a bid to find a new direction in which now a bloody horse turned out in front

of him!

But to be serious, the real thoughts this incident inspired him to

were that solving a mathematical problem in fact does bear a strikingly

resemblance to, say martial arts: you can attack left, or right. You can go in

full attack, or test and explore the enemy with limited skirmishes. Going, which

is a trifle, from there to hurdle racing, you see the profound similarity of man

and horse. To make matters worse: horse performance allows better data

collection, so any conclusions about horses tends to be better founded.

This regrettable - but possibly promising, for this bulky

book about him has just started - incident made him realize, only a few weeks

ago, that he really was not keen to stay a mathematician for the rest of his

life. It had taken place well beyond the Austrian borders. And now he lived in

this silly little castle in the outskirts of Vienna.

He tended to think - and as the author of this book I opine the

exaggeration in that not to be too exaggerated - that he had all talents

to engage successfully in whatever he would choose. Moreover, he was tall, blond,

muscular and trained like a panther. Nor did he need money. What to do?

He had decided to devote this year to consider what use of his

capacities could give true meaning to his life.

14 Old friends.

Back in Vienna Ulrich could again regularly visit his old friends

Walter and Clarisse. Walter was of his age, a youth friend. Clarisse, eight

years younger, somehow joined them later on and married Walter, which Ulrich had

regarded as a selfish disturbance of the group. But everything had changed:

Walter, who had done many different things and, contrary to Ulrich, consistently

got extolled for it, and was considered promising in many areas, everywhere

sooner or later had acquired a fear for attachment and thus now had reached a

state of stalemate and isolation. Clarisse thought she married, as she was

ambitious to, a genius, but now was the only one left believing in him. In no

respect she had stranded together with him, and thus had gained Ulrich's respect

and interest.

Walter had shown to be able to take root and grow everywhere, but

always had torn himself loose for fear of impurity and delusiveness. Fear for

half-hood had now made him half himself, with an easy job, a sketch-book of

which every used page immediately got thrown away, a house at the far edge of

town and a grand piano on which to play for consolation like a method of

stupefaction.

A second consolation for Walter was his thought that Europe was on

the way down. Hopelessly. So for that, fortunately, he himself carried no blame

either.

Now, without, like Walter, searching our footing in pessimism, we

have to concede there was something with the times. Technically and economically

the second half of the nineteenth century had developed fast, but in creative

respect most efforts had been exercises in repetition. There had been great

artistic innovators but they had been standing at the side line.

Then, suddenly - Walter and Ulrich happened to be young - something

started to shake and move, but whether it was a new art, a new human being, a

new morality, or maybe even a new social order, everybody had different thoughts

about it. But loudly so! And practical men came along to go into action. And

though of every new thing you heard about the contrary was to heard as well,

from a distance you could see it was a huge fire.

Well, let us not exaggerate, for we speak only about that thin

layer of the populace called intellectuals, the layer that, as we now all have

been reminded of in the harsh way, shortly after got cleared by that familiar

type of men descending upon them who have those decided and rough handed

opinions and a natural talent in eradicating diversity.

Such a splendid moment of creative budding of course never could

have had any major significance in the history of a biological species like

mankind, but all the same it was a remarkable little happening, and Walter and

Ulrich had witnessed it. When they were young one thought led them to the next,

and often it seemed like they had invented them personally, at least the two of

them together. Splendid thoughts giving you that glorious feeling "Here am I,

look at me!". The imagination seemed to have risen to power.

It is a pity that no important thought is useless for stupidity.

With the petrol-combustion engine you got those motorbike drivers passing before

you with that weighty mimic of a roaring toddler. And if there had been lady

swimmers somewhere having their muscles treated by one of those masseurs, you

know, those ones who know how to keep looking like butchers in the face of

cameras, then a few hours later a newspaper would get dropped in your box

featuring a sharp picture of it all. And, don't forget: genius-race horses. All

of this should be accepted by everyone who embraces his own time, just like

electricity, wireless communication and high rise. Ulrich could feel the

occasional amusement, but he did not succeed to give himself to it.

Sometimes Ulrich imagined how the great church philosopher Thomas

Aquinas, d. 1274 after having pressed, in loads of volumes, all frightful

enlightened Greek-Arabic thoughts newly imported in his times in the Procrustean bed of

Catholicism painstakingly

and not without shedding some blood, so well that he would not have to

wait long to become a real saint, would suddenly stand here, and then

wooffff!! a tram along his nose. He could have started all over!

While Ulrich planned in the coming year to search for himself by

means of participating observation, Walter wanted, it seemed, walk the jogtrot

of his easy library job his father had found for him and for the rest be at home

with as few thoughts as possible, which, he had found, was best achieved by

playing the piano.

Clarisse, of course, should have been Walter's main consolation but

she did not feel the vocation. As far as music was concerned Walter judged Bach

the top after which things had gone down, but he played a lot of Wagner, which

even deprived Clarisse of her corporeal lust for him.

It will not be a surprise that Walter imagined that his suffering

could be alleviated by having a child, and that Clarisse did not share the

ambition at all. More generally, Walter utterly failed to convert Clarisse to

his pessimism. She even stubbornly kept believing in his genius, after all that

is why she married him.

Something in her scared Walter. And this got more serious since the

return of Ulrich. "I do not want to know what Ulo told you" he once said after

she had returned from a walk with Ulrich, "that so called power of him that

fascinates you so is nothing but emptiness". While saying that he sat down at

the piano by way of protection.

Clarisse smiled.

"He is a man without qualities". This expression suddenly pleased

him.

"What is that", Clarisse giggled.

"Nothing. That is nothing at all. In everything bad he sees some

good somewhere and the other way around. The whole thing has no fixed shape,

what he says is determined by accident, and a little later he says something

else ... well you probably do not understand me".

"O I do, but that's what I like about him".

"You can't be serious"

Meanwhile Clarisse had started eating a cheese sandwich, so she

could only laugh with her eyes.

In these attacks of rivalry, old frustrations popped up in Walter,

from the times they were small boys and he was the weakest of the two.

8. Moosbrugger.

Moosbrugger was a broad-shouldered always benignly smiling

carpenter, whom many a woman would follow without hesitation if he told her he

knew the way she had been asking for. But he had murdered a prostitute, and the

remains did not look like he had killed the victim in the most efficient way

within reach.

He got in the newspapers, which turned out to boost sales, so now

he was an Austrian celebrity. To maintain this happy combination as long as

possible, his earlier murders, detainment and psychiatric treatments got played

down. And psychiatrists maintained, both in court and press, interesting

disagreements about Moosbrugger's compos mentis. He became proverbial and

essential newspaper amusement.

For Ulrich as well. He studied the news carefully. From early age,

Moosbrugger had roamed around in towns and countryside, hunting for jobs as

carpenter aid. But often they were not to be found and he ended up sleeping in

stealth on the straw of some barn, to be thrown out by a furious farmer, to go

look for something edible badly watched by its owner. The lifestyle regularly

led to confrontations and every time he won one it got added to his police

record.

No use for him to approach women of course. His forced abstinence

twisted his mind. Voices would call him day and night, he had already told the

judge after his very first murder.

He had profited from his sojourn in jails and madhouses by learning

high German judicial and psychiatric jargon, so you now could hear him say:

"this should be regarded as the basic tenet underlying my brutishness".

In sum: Moosbrugger was ideal popular entertainment. And he enjoyed

it himself.

Psychiatrists who preferred to quickly label him with some

multisyllabic terms of Greek etymology to lock him up in a madhouse were, of

course, the enemy of the people. But no worries: with broad approval - not to

use the word "ovations" - Moosbrugger showed himself on top of these

professionals, and showed them all corners of court. They did not stand a chance

and he proved irrefutably that he did not belong in a madhouse.

And thus it ended, Ulrich went there and witnessed it, with the death

penalty, after which Moosbrugger, while taken away said: "I am satisfied though

I have to concede you did sentence a psychiatric patient".

Which in Ulrich popped up the thought that if humanity as a whole

could have one single dream, this would be Moosbrugger.

19. A letter to Ulrich from his father.

My dear son,

... months passed ... not much news ... hear speaking about you in

laudatory fashion ... but first steps always boisterous ... after which ...

forgotten ... at you age now ... high time ... no neglect of social and

scientific relationships ... His Excellence Count Stallberg ... would like

you to ... provided you manage to win him for you ... future reassured. The

issue is this:

At the end of 1918 Emperor Wilhelm will celebrate the 30-year

jubilee of his office. News reaches Vienna that preparations have already

started. It would be a disaster if those Prussian celebrations would throw the

70-year jubilee of the office of our own Emperor in the shade. That is why,

though we still have five years to go, in our own Empire a movement has started

... our jubilee is a few months later ... hence the fortunate idea has come up

... to make the entire year 1918 a Austrian Imperial Year ... a for your age

highly honourable place in the committee ... and please, as I told you so many

times ... I am almost ashamed when I am asked again about you ... do visit

Sectionschef Tuzzi. His wife, as you know she is almost a niece of you, has an

important role in the committee.

Father

SECOND PART

___

AND THUS IT

HAPPENED

20 For thoroughness and ardour, qualities seem not required.

Well, with nothing to do except a single court case of a lunatic

murderer, Ulrich decided to follow his father's recommendations. Curiosity. That

was about it. But yet, it happened: Ulrich decided to allow reality to touch

him.

It already started with the driver, who stopped before entering the

Hofburg area, for "inside he was not allowed to stop". The first thing Ulrich

felt of the power he was approaching was by failing to change the driver's mind

on this. After passing all those yellow uniforms and helmets, silent and

straight in the sun like birds on a sand bank, he was led, walking in one of his

best suits, to Graf Stallberg. Short inquisitive looks from left and right made

clear to him he was nothing here.

There he arrived at the count's room. It turned out that at this

level of portliness one wears his whiskers shaven at the chin, just like the

ordinary Kakanian is used to see it of official receptionists and

station-masters, suggesting that this is what you tend to wear whenever you

profession is based on subservience.

After politely having answered some questions about himself Ulrich

suddenly thought of Moosbrugger and said: "Your Excellency, could I use this

occasion in favour of a man who recently unjustly got sentenced to death?"

That surely made the count's eyes open widely. And he immediately

saw how embarrassed Ulrich was by his own initiative, which prompted the count to

a truly magnanimous benevolence, for he conversed for a while about it as though

two gentlemen were engaged in state affairs.

But in a tactical, yet decided way he conducted the conversation

back to Ulrich's father and the Imperial jubilee, while at the same time writing

a letter to the president of the committee stating: "... we are fully entitled to

hope to have found an assistant with thoroughness and ardour ...", and in no

time Ulrich stood on the corridor again, with the letter, as a child that got a

sweet at goodbye.

Flabbergasted he looked at the letter and mumbled in himself:

"f...k!, this made me land somewhere I did not want to be at all".

There was something here. What the hell was it? Ulrich tried to

trace it on the way out, and he succeeded: this was a surprisingly real place.

(He should have realized that a few years earlier, when at the age

on which Napoleon, so admired by Ulrich, made his first visit to the Emperor of Austria

and beat his army so thoroughly that the latter, in gratitude for being allowed

to get off with his life, loyally did what he was told for a decent number of

years)

21. A count with vision (vision under construction).

In another room of the Hofburg, at least as beautiful, His Serene

Highness Count Leinsdorf, the spiritual father of that noble jubilee initiative

in the meantime having become known as the "Parallel Action", had a passage read

to him of Fichte's Reden an die Deutschen Nation. He had ordered to

collect the book because this passage might be suitable to win over parts of the

nation who identified themselves as German rather than part of the

Imperial-Royal Austrian-Hungarian Empire. But unfortunately the passage

contained something protestant. He told his assistant the book would no longer

be needed and could be returned to the library.

"So we keep thing things the way we have them", the count ordered,

"four points: Emperor of Peace, European Milestone, True Austria, and Property

and Education. You can write the draft".

Now the passage had turned out unsuitable, the count felt a bit

relieved not to be forced to make the bow for that type of subjects. They would

come by themselves. His Serene Highness was still deeply hurt by the Austrian

defeat in the war of 1866 against Prussia, that made Prussia the leading power

in the German sphere and had forced Austria to satisfy itself with what was

lying behind, full of alien nations, and in as far as there were Germans there,

it had become fashionable among them to despise the fatherland of His Serene

Highness, since, after all, the German Nation was about to be constituted under

the leadership of Prussia.

No, here was a noble job for the Austrian nobility. The Austrian

Imperial jubilee was a God given occasion to repair and reinforce the unity of

the fatherland.

22. A giant chicken busy to spread her spirit.

When at last out of the Hofburg no hair on Ulrich's head longer

thought of visiting count Leinsdorf, but he remained curious about his "big

niece", whom his father almost begged him to go and visit.

The inconsistency of the results of his different enquiries were

puzzling: "beautiful and shrewd", "amazingly stupid", "simply the ideal woman".

Wherever he could ask whether she had a lover, he got answers in the vein of:

"strange, I never asked myself".

A beauty, but of spirit, Ulrich had suspected, a second Diotima.

But she called herself Ermelina (while her name just was Hermine).

At the time she had met Tuzzi, who had still been a civilian officer somewhere

down in the entirely feudal Foreign Office, hence without any perspective, her

parents had considered him a good marriage partner. Miraculously, Tuzzi rose to

become the right hand ("and head", gossip went) of the minister of its most

important section, which had made Diotima's disciplined secondary education fruitful

in her contacts with all those important people now frequenting her house for

need of Tuzzi's favours.

At entering her house Ulrich was surprised. She turned out a highly

attractive lady, tall, of about his age. At meeting he held her hand, fat and

weightless, a bit to long. It felt like a thick leaf in spring, so it seemed

that the long pointed nails could fly away into the improbable any moment. The

hand, after all basically a rather shameless organ touching and probing

everything like a dog's snout, had overpowered him for a second.

Diotima started with an explanation of the Parallel Action. A lot

of spirit passed but in between Ulrich regularly spotted the black-yellow tape

that the servants of the Emperor use to bind their official files. But she did

not need much time to reach the: "We must and want to realize a very big idea".

"Do you have anything specific in mind?"

Well, you know, Ulrich should really not have asked this. First: of

course she didn't. Second, he knew very well that in being told such a thing one

ought to nod with a deeply impressed mimic. And in silence.

He had put Diotima on the back foot, tried to restore her with a

joke, but utterly failed to make her smile.

Not much later he understood his audience had expired. He said

goodbye with the impression that the corporeal part of their meeting had fared

better. From both sides.

23. First

interference by a great man.

Dr. Paul Arnheim, about forty, son of one of the richest steel

magnates of the Prussian Empire, a jew, had just arrived in Vienna.

He was thought to have the ambition to surpass his father and

prepare for the office of government minister. Tuzzi, with his excellent foreign contacts,

knew that would never succeed, unless the world would perish first.

(and even

Tuzzi did not yet know that the world would soon adopt this daring project so

successfully that within five years all non-Austrian parts of his beloved Empire

would be within the competence of his very own department of foreign affairs).

Rachel, Diotima's chamber maid, called "Rachelle" of course, was

talking excited about all she had heard: Arnheim

was told to have come

with his own train and have hired an entire hotel. And his boy was a negro.

Diotima believed nothing of it (though the last was true), but she

let her talk since she could be pretty sure this great man would soon be at her

doorstep.

She was not at all nervous about that prospect, for in the last years

she had become the shining host of her own salon, now chosen by His Serene

Highness Count Leinsdorf (an "office" he even said) in directing the Parallel

Action. So here could and had to be a warm welcome for every loyal citizen of

the Empire: the Czech, Slovak, Silesian, Galician, Transylvanian, Hungarian,

Croat and Bosnian who would be enabled to express his positive feelings for the

Emperor-King and ponder the ways in which to give solemn and celebratory shape

to them in the coming Imperial Year. 1918. A salon for all, so why not for an

exceedingly rich Prussian jew?

24. Property and education.

An "office", as Leinsdorf said. Naturally, a reichsfreie

count (directly under the Emperor) like His Serene Highness, was and ought to be

of the deepest religiosity, but, being the owner of quite some factories, he

realized that not all skills crucial to these modern times were exhaustively explained

in the Bible. Yet he was deeply convinced of the utter necessity to cherish the

tie between business and the eternal truths in profound general civil education,

and in that sense His Serene Highness not only was a religious, but also a

civilian idealist.

And it was from this perspective that His Serene Highness viewed

Diotima's salon, where you could meet Kensinists and Kanists, you could see a

linguist of Bo searching for words in a conversation with a physicist of

elementary particles, hear a toncologist excuse himself for nearly spoiling his caviar on a quantum physicist, not to mention the representatives of

literature and poetry, who always had to be selected carefully and in moderate

quantities, and hence could wait in vain for their next invitation when the

newspapers had started to employ more superlatives to some colleagues.

But the non-professional aspect was important as well: in these

times in which economics and physics started to press theology from behind, this

aspect related more and more to bank directors, politicians, top government

officers and their spouses. And they were far from rare in Diotima's salon.

Finally: the women. In this wide realm Diotima did not primarily think of intellectual women, but had,

from her elevated idea of the "unbroken woman" a preference for "ladies", who understood that being a

lady is a full and complete vocation that only pales when it comes with side

activities. This guideline made, as a collateral advantage, her salon, in which

a lot of the conversation was à deux, very fashionable in circles of

young men of high nobility.

Count Leinsdorf did stop short of calling the resulting salon-mix

"true distinction", so he used the keywords "property and education". And the

reason he called it "office" was that in His view "office" was not limited to

staff of Imperial ministries: literally all roles in society, worker, ruler and

craftsman, you name it, essentially were "offices".

An evening convention in a salon is prone to look like a unity, and

that was what Diotima called "culture". She enormously appreciated Leinsdorf's

intense interest, especially since she did not know that His Serene Highness had

been hesitant to receive all these people from quite diverse backgrounds in his

own palace, for reasons of monitoring and security.

Yet, Diotima was not problem-free: the spirit turned out not only

great but it chiefly was a huge lot and difficult to grasp in its variety. Count

Leinsdorf could easily walk in, say something about profound education, and go

home again. The chief bulk problem was the width, not the depth. If you only

just witnessed that

even discussing the simplicity of ancient Greece or the meaning of the

prophets while that night you invited two experts in the field instead of

one, the case got crammed with doubts and unconfirmed hypotheses. And that was

one of the reasons the company tended to split up in groups of two: thus one

could at least keep an overview of the differences of opinions rising in

conversation.

Moreover, the warmness between the nobility in her invitation lists

and the nobility of mind that her

ambition had inspired her to herself, did

far from always develop to her satisfaction.

All these problems she had bundled, in the analysis of the adverse forces

in her life, in the awareness that not only do we live in a time of

culture, but also in a time of civilization, by which she meant everything that

sadly resisted her attempts to elevation. And her husband was part of that.

25. Diotima's concept of civilization (or: the suffering of the

married soul).

To Diotima, it felt like she had no soul. If she had one, it felt

like being hidden totally out of reach.

She had the impression that in her youth she still had regularly

caught a glimpse of it. She had browsed the Bible but those mysterious and vague

words had not given a clue. It would have cheered her up had she ever dared to

discuss the matter with a less unfortunate human being. For she would have

learned that it is generally sensed as a flimsy being that creeps away as soon

as you start about algebraic progressions.

Maybe what she had in mind was a little capital of power to love

that she had still been the owner of when she married, and for which Section

Chief Tuzzi, a cerebral utility-person, had not been a suitable investment: a

hard working man with a strict day schedule in which everything had its place,

who, when returned home, swiftly went to his study to keep his superiority in

knowledge over the rest of his department on the desired level. Erotics had its

place as well: once a week before sleeping. Just before sleeping.

Before his marriage Tuzzi had been a brothel client of the

non-annoying and calculable sort and he had taken that protocol into his

marriage. Once every week Diotima betrayed, as it were, her body to him, and

that subjection, though she knew it was not held immoral, filled her with

disgust. Tuzzi was unaware of any problem.

And thus she had become a fervent and ambitious idealist. She

sensed that her social expansion was not taken very seriously by her husband,

which fanned her fire by some grudge and rivalry.

It was in this time that Dr. Arnheim and his little negro arrive in

Vienna and shortly after got received by Diotima.

26. The unification of soul and economy. The omnipotent man

wishes to enjoy the Baroque magic of old Austrian culture, which triggers the

birth to the Parallel Action of an idea.

Diotima had sent Rachel out and enjoyed having the little negro all

for herself for a while. Her thoughts (and polite questions) touched his

benefactor Arnheim, heir of a world wide steel concern, writer of books she had

read with approval, about the unification of the economy with the soul and about

the power of ideas.

With approval indeed, for Diotima heard everywhere that politics and diplomacy of the

ancient nobility stood with one leg in the grave and

that the disgust of scientific experts also started to be felt more and more.

What she liked as well was that he did not look jewish at all

(while her physical appearance had made on Arnheim a slightly corpulent but

otherwise Hellenistic impression, with just that little bit of extra flesh to

not make it too classical).

And then his motivation to visit Austria. That had charmed her

enormously: he had said he had needed a repose of all that calculation, the

materialism, of the empty rationality, in the Baroque magic of ancient Austrian

culture!

Hearing that she had been unable to prevent herself telling him

hear total endeavour was to liberate the soul of civilization, an issue "all

notable circles in Vienna nowadays were occupied with".

Arnheim just managed to let her finish and said at once that,

yes, "new ideas urgently had to be brought into spheres of power".

By which an idea was born that had thus far lacked in the Parallel

Action.

27. Essence and content of a great idea.

In the first instance, this great idea showed itself to Diotima in

the form af the certainty that the Prussian Arnheim should be charged with the

leadership of the great Austrian initiative, though since the Parallel Action

was partly based on some undeniably Austrian-Prussian rivalry, this would

require some magnanimity. But wasn't this exactly what the great initiative was

about?

But this first appearance was merely the body of the idea. As far

as the soul was concerned, Diotima's first feelings were chaste and decent, and

there appeared in her innocent mind the muscular body of Ulrich: in the vicinity

of an Arnheim something might grow out of this young man!

28. A chapter to skip if you do not have the work at thoughts in

high esteem .

Ulrich once got the idea how to use some types of differential

equations to describe some specific physical processes. It still regularly

resurfaced in his mind and so he sat in beautiful weather, inside behind closed

curtains at his desk, messing around with mathematical expressions.

But his test example, a state-equation of water, distracted him. His

mind

jumped to all water on our planet and the misunderstandings about it from the

times of the ancient Greeks until, well, today, really. And how dangerous it had

been to point at them. Even today, those who had learned that some could change

it in wine, and that it can be used to baptize people, and whom this information

had endowed with a profound feeling of security, could get so unbearably sobered

by scientific truth that to monitor subsequent events the contribution of close

police alertness would be prudent if not required.

He opened the curtains and wondered how this scientific thinking

could have made this astonishing progress in the last few centuries, especially

when you consider that every thought immediately disappears when someone says

that somebody else has a pimple on his nose.

Dreadful.

29. Bright moments and interruptions of normal consciousness.

Ulrich had agreed a sign with Bonadea to indicate he was at home

alone. He always was, but did not make the sign, though he knew that sooner or

later she would announce herself anyway, and she did.

When angry she was much more attractive so in short notice

everything had happened again.

Half in his thoughts, he hoped she would dress herself quickly and

part, driven by obligations. But she did not, as he noticed, checking in

stealth. She even interrupted dressing entirely, apparently piqued by his

lack of attention, waiting for him to take an initiative. Half dressed she now

lost herself in an art book.

Suddenly Moosbrugger submerged in Ulrich. An entire piece of the

interrogation, literally, as if a recording got played in his head. Did he hear

voices? He first got haunted by some anxiety, but if indeed this was a first

experience with such a thing, he decided, it was not so bad after all.

When Bonadea finally had put away the book,

to cash in, half dressed and in hurt pose the reconciliation she aspired,

instead of that she had to elaborately endure Ulrich's view on Moosbrugger. She

tried to get rid of this scary carpenter by swiftly choosing the side of the

lady whose untimely decease he had caused, hoping that Ulrich's interest in the

murderer would cease now he was the only one of the two left, and the way would

be cleared for a conversation from woman to man.

But Ulrich wanted to know if it was her

consistent habit to choose for the victim, and if so, how she morally justified

het breaches of marriage.

Breaches of marriage! Especially the plural

offended Bonadea. She sat down and directed her gaze to the ceiling with a

despising facial expression.

32. A forgotten, history of utmost

importance with the wife of a major.

What was this Moosbrugger doing in his

brain? What affected him, Ulrich asked himself, in that hassle, that yellow

press issue, virtually restricted to Vienna, about how and where exactly with

his knife he ... this gruesome game with a willing victim of the media. He did

not consider for a moment to interfere in it, at whichever side.

The whole thing touched him somewhere else.

He thought of that sentence: "Even if the souls would be visible a sodomite

could walk through the crowds without any sense of evil". He had read it in

Maeterlinck, whom meanwhile he had come to judge worse than perfume on bread,

but it rendered that opprobrious feeling never in his life to have returned to

those other, those real sentences of that mysterious language, of soft dark

innerness, so contrasting to the authoritarian voice of math and science.

He had been around twenty when something

weird had happened. He fell, well, let's face it, he fell in love with the wife

of an army major, not any more so young, with some artistic talents that she,

for reasons of her social standing, only showed on weddings and parties. To

Ulrich his feelings for the woman had been disconcerting for thus far he had

identified love with fucking. So it felt like a disease.

To the woman in question it should have been

disorienting as well: hearing a twenty year old lieutenant inform her, as

through a funnel filled with turbulent thoughts, about stars, bacteria, Balzac,

Nietzsche en things like that.

Some totally undeliberated horse stumbling

during a ride had degenerated, before any of them realized, into serious

kissing. Only after that had started both sides started independently to wonder

what one suddenly was doing.

When Ulrich wrote her he had to leave for

strictly unavoidable travel, the wife of the major felt, under her tears, at

once relief. Ulrich took the first train to the nearest coast, to take no

chances boarded a ferry to an island, where fortunately the whole thing went

over.

Well, and now this Moosbrugger ...

33. Breach with Bonadea.

But we left the story where Bonadea was

lying on the divan. After noting that was to no avail, she had given up her

demonstrative ceiling staring. After some more irritated talking past each other

she brusquely resumed her dressing, with had no effect either. From her

movements Ulrich inferred that she would not come back

And indeed, with some effort, but bravely,

she kept her sadness to herself, put her veil back on and walked out of the

silly castle, correctly accompanied by Ulrich.

34. A warm jet and a wall that got cold.

That done, Ulrich had lost his appetite for

math. He resolved to visit Walter and Clarisse in the evening, though they never

came to him. In his hall he wrote a postal notice to announce himself. The

objects at the wall of course always hang still, but now they seemed to do so

only because the time had been stopped, especially those antlers that looked

like Bonadea when she did her hair.

Everything there seemed to have stopped to

take leave of its role for a moment: I am purely accidental, necessity spoke.

With pimples and pustules I would have been equally attractive, said beauty.

Which was the feeling of all moments in

Ulrich's life that he remembered to have been decisive.

He took to the street to post the message.

There everything moved again and he was between all those people doing their

people-things, like a wave between the waves. A nice tickling feeling after

several days among differential equations.

Ten, fifteen years ago, when at grammar

school and with that passionate and feverish Viennese cultural revolution going

on, it had felt even better on the streets, though there immediately had been that oppressing

suspicion that the false and empty slogans echoed in the most powerful and

profitable way, as a result of which most heroes of that time indeed had let

themselves be smothered in one or other soporific role.

Most people love to see the world being

prepared for them, stuffed with all comforts. And in most periods of history

this is catered for: the world, the simple range of options clearly indicated,

so well finalized and complete, like chisseled in stone, making you feel like

being a superfluous haze blowing over it. But few are aware of it, while most

people in middle age no longer know how they found themselves, their wife,

character, profession and success, while at the same time they realise very well

that there is not much anymore that can be done about it. They call the whole

complex their qualities, and would not like to hear that they simply lie

waiting, like glued on the sticky bottom of a carnivorous plant, for their end.

In that stage the memory of one's own youth

has largely faded. That was the time where counterforces seemed at work, the will

to break loose, fly, be different, if necessary by endangering one's own life.

But even the targets for youthful movements

one likes to find ready to pick: whether it is a new beard fashion or a new

thought, once on display, the youth throws itself on it like sparrows on

breadcrumbs. Napoleon already knew how to make youth aspire to die in battle by

the millions, and now entire platoons of scientists set out to find how to derive

unprecedented economic advantages from adolescent energy.

Ulrich reached a little square where during

the Viennese cultural revolution his friends had lived (though he had not known

them all in person, they were all his friends). But these people, now

professors, celebrities and names, stranded in petrifaction, already for a long

time lived elsewhere, and the little square now was like a fossil as well.

But everyone telling its history will say:

there were ...

35. Director Leo Fischel and the

Principle of Insufficient Reason.

On that very square he encountered Leo

Fischel, an old acquaintance, now "managing clerk with the title of director" at

Lloyd's Vienna. He was irritated since he had put aside for too long a letter

from count Leinsdorf, which most probably had something to do with his healthy

commercial opinions concerning patriotic actions instigated from higher circles:

"stinks".

And in this he felt vindicated by the

frequency of occurrence of an adjective he fortunately never encountered in his

business correspondence: "the true ... ".

But Leinsdorf was not merely from high

circles. He was an important business man as well. Lloyd's did his stock

exchange transactions. Leo had to do something.

Ulrich might be of help now, Leo had heard,

he had something to do with it. Though in a hurry he quickly approached him:

"Hello, Ulrich! Listen. I know what are patriotism and Austria, but what is true

patriotism and true Austria? Tell me."

"The PIR", Ulrich answered.

That fell well: in Leo's world it rained

abbreviations all day. But the distrust was not taken away: "No, be serious for

a second, I am late for a meeting".

"The Principle of Insufficient Reason",

Ulrich said, "as a philosopher you know what it is, and how man goes straight

against it by creating only what has insufficient reason".

Leo felt tempted to argue against this but

his hurry won it: "listen, I have to do something, I got that letter, please

help me a little".

"OK. The best is to think of an enzyme or

catalyst", Ulrich ignored Leo's hand, which made a throw away movement, as well

as his glance on his watch. "It starts a process but at the end nothing of it is

found in the result. Think of the fertility of wars, and all dirty tricks and

malice it produced, in boosting human progress".

"Oh, please", Leo whispered.

"I assure you, nobody yet knows what 'the

true ... ' is, but you bet: it is on the verge of becoming real".

Thoughtful, Ulrich saw Leo running away from

the square, to his meeting.

36. In line with to the abovementioned

principle the Parallel Action exists tangibly before it is known what it is.

Leo Fischel believed, like all bankers in

the world in august 1913 did and would keep doing for exactly 16 years to come,

in progress.

But he felt he could not trust this to be

the same thing as Leinsdorf's progress. And since he had developed the habit to

equate expertise in some issue with the daring to invest capital in it on your

own account, he considered himself not an expert in the issues that Leinsdorf

dealt with in his letter.

"Not knowing" meant, in Leo's banking

routines: finding an expert adviser. In this case his first thoughts went to his

director-general, who fortunately also had received the letter, had discussed it

with his boss, so Leo could limit himself to listen for a while with the facial

expression of awe, and modestly retire.

This consultation did not remove his first

impression of things, but made clear to him he should keep this impression to

himself, also at home - his quarrelsome wife was from circles of high

bureaucracy, and he now understood her background had made him the only one

in his modest ranks who had received an invitation - and that this issue would

not burden him in any way as long as he kept showing himself impressed whenever

the Parallel Action was discussed.

Meanwhile in Lloyd's, high above Leo, von

Meier-Ballot, the governor, had concluded that this, if he managed to talk and

donate with some agility, could lead him to an appointment as minister, which

would constitute not a small windfall for himself and his bank.

Von Meier-Ballot's impression got reinforced

when he met the ex-ministers von Holtzkopf and Baron Wisnieczky, who had been

requested to serve as provisional ministers during attempts to form another

government that could count on sufficient support in the Empire, and that done,

had been relieved to receive the request to vacate their functions for the next

failed attempt.

Thus Holtzkopf and Wisnieczky knew the

problem from within and who knows something like Leinsdorf was trying now ...

von Meier-Ballot decided to closely monitor the developments of the Parallel

Action.

Thus even here Leinsdorf's method, that he

himself called "first give people knife and fork, then teach them how to eat

decently" worked.

37. A journalist invents the "Austrian

Year": count Leinsdorf in trouble. His Serene Highness longs vehemently for

Ulrich.

Ulrich, we bring back to mind, had decided

not to use the letter he got from count Stallberg in which the latter had

expressed himself positively about Ulrich's "thoroughness and ardour" and

proposed him as the honorary secretary of great initiative. Which means he would

not visit His Serene Highness count Leinsdorf, though you could almost say that

as a subject of the Empire he got the order to do so. Ulrich had limited his

interest to Diotima, as he had baptized her.

Also we remind the reader of Diotima's

sudden view of Ulrich, at the moment the pervasive importance of Arnheim had

started to twinkle on her firmament, as a minor but well-shaped star in the same

constellation.

Now we shall learn below how count Leinsdorf,

who merely had heard about Ulrich, desperately started to long for him, yes,

even one day prayed he would surface - though the next day he already felt

ashamed about it.

Something had gotten out of hand: a

journalist had heard something and had, to fill his article, produced some

meritorious fantasies about and "Austrian Year" that would be in the making.

This had triggered lots of reactions from all kinds of sides. Whoever encourages

the public to be "Austrian" may meet little enthusiasm but an "Austrian Year"

turned out, for many, a good occasion to bring all kinds of issues under the

attention, such as a vomiting pan that can be shut with a simple grip, the

abolition, in public places, for reasons of hygiene, of salt pots from where one

takes salt with his knife, the general adoption of the stenography of Öhl, the

return to a more natural life style, a metapsychical theory of the movement of

celestial bodies, the simplification of the system of government and the

reformation of sexuality.

Count Leinsdorf had hoped to trigger: a

powerful message arising from the bosom of the people, a message of unity and

patriotism, under the guidance of scholarship, the clerical world and those high

industrial names

well known from charitable manifestations, but this popular creative frenzy of

world improvement, this sudden cacophony of screams from innumerable

ignoramuses demanding to be liberated from their spiritual dungeons filled him

with outright horror.

His Serene Highness ordered for a search of

Ulrich, whose connection to his silly castle had not yet reached the

population register. Neither could Diotima help him, who, by the way opined now

to have a much better candidate for the post of honorary secretary of the

initiative. But Leinsdorf curtly told her he could not use a Prussian, not even

a reform Prussian, and that things would get tough enough without something like

that. And he (the idea to simply contact Ulrich's father should in this novel,

for reasons that will become clear below, not come up in his mind) told her, he

suddenly got that idea, that he would go at once to his friend the President of

Police, who after all should be able to find every citizen of the Empire.

38. Clarisse and her demons.

Quattre main was raging again when

Ulrich's announcement arrived.

"That is a pity", Walter reacted being read

the message.

Then the piano piece rolled off again as a

steam train, before it a multiple series of busy staves, behind a sounding

landscape to listen to.

It went very well. "Would this be the day?",

Walter asked himself. He did not want to get Clarisse back by force. The

awareness had to surface in her spontaneously en then she would softly bend over

to him.

But even before the last keystrokes her

head had already parted elsewhere. In an unstable cloud images rose in her,

melted, merged, overlapped, disappeared, that was normal to her. Often many

thoughts at the same time, a little later none at all, but then you could feel

the demons, standing behind the stage. And the order in time of experiences, so

helpful to many people, was a kind of veil to Clarisse, with it folds sometimes

densely together, then dissolving in a hardly visible little haze.

Now she was suddenly encircled by Ulrich,

Walter and Moosbrugger (whom Ulrich had told her about).

One should really never stop playing piano,

she thought. She threw the score back to the front and started the piece all

over again.

Walter laughed and joined.

"What is Ulrich doing with all that

mathematics?", Clarisse asked.

Walter shrugged his shoulder while playing

on, as if he was driving a car.

One should play on till the very end,

Clarisse thought. Suppose you would not stop until you died, what of all

contrary things people say about Moosbrugger would turn out true?. She had no

idea.

She knew that some time she would do

something tremendous, but she had no clue what it would be. She felt it most

clearly in music and she hoped Walter would become an even greater genius than

Nietzsche, not to talk about Ulrich, who long ago gave her Nietzsche's work.

She had already proved her mettle: she had

learned to play the piano, now better than Walter. She had read an awful lot of

books, now suddenly appearing as black birds flitting around a girl in the

snow, changing into a black wall with white islands painted on it. The black

scared her. "Is he the devil?", she thought, "has the devil become Moosbrugger?"

Her fingertips plunged back in the waterfall of music. On the bottom of the creek snakes, twists and coils. She entered

Moosbrugger's cell, her heart trembling, but when that resided she relaxed and

filled the entire space with herself. She put her hands on Moosbrugger's eyes

and he changed into a handsome young man. She now stood next to him, very

beautiful herself, not so skinny and weedy as she really was.

Walter's playing got a bit unsure and she

immediately knew the cause: the child. He wanted a child. That was her daily

battle.

She jumped away from the piano and threw the

cover down. Walter was just quick enough to save his hands. He knew: this was

Ulrich. He awakened something scary that deep down in her was pulling at its

chain. He feared it.

No she did not love Ulrich, Clarisse

answered him angrily. But Walter sensed a stupefying collateral that had nothing

to do with anger.

It got dark.

39. A man without qualities consists of

qualities without a man.

Ulrich did not go to Walter and Clarisse,

for his conversation with Leo got him submerged in thoughts. That extra social

echo that consistently lacked in case of truth, and then always sooner or later

lies would manage provoke it, "only lies produce progress", he thought, "I

should have told Leo".

Ulrich had no qualities but this of course

did not mean he had learned nothing. He did things, in a sense even

passionately. That is how he learned B would follow from A and how to do

specific things like boxing, horse riding, mathematics. But this had merely

built itself up in him as a huge catalogue of qualities without a man, in which

this man without qualities could browse without sensing any personal

involvement.

It is not so difficult to describe the

basics of this thirty-two year old man Ulrich: an astonishing mental agility

indicating a wide range of talents and a dominant instinct of attack. His method

of learning consists of using others as inspiration for experiments with himself

but he will never identify with anyone under some banner like "I want to be like

him". He does not acknowledge general rights, only local personal rights he

judges some individual has earned. Nor does he recognize the existent view on

duties, instead, and sparingly, his thoughts touch on one he decides he should

adopt, many of which later on he discovers were not good and he should drop

them. He never trumpets them forth.

Or: had Ulrich died as a single fertilized

egg-cell, his life would have been perfect. Now he was wrestling with all those

bits and parts.

Everything seems to have a spirit: the

spirit of loyalty, of love, the male spirit, the educated spirit, the greatest

spirit of out times, we hold high the spirit of all kinds of things, we act in

the spirit of our movement, but is is hard indeed to encounter a spirit on its

own, unconnected to anything. In this book we do.

(In case the reader vaguely senses that what

we just called "the basics of Ulrich" are in fact his qualities, I do hope this

came in your mind (like in mine) together with Clarisse's black wall, that a

slight fear similar to hers is coming up in you, and that you can keep this

slight fear at safe distance by finding some frantic activity comparable to

Clarisse's life long piano playing, and my life long writing).

40. King of spirit arrested, secretary

of honour found for the Parallel Action.

As said: it got dark.

For quite a while Ulrich had sauntered on in

that dark, while thoughts had streamed through his head that would be too much

even for a talented author to put down in a few pages, when he, yes, we have to

say, got attacked from behind by a quality.

It went like this: a workers' newspaper had

written critically about the Parallel Action, and a bourgeois newspaper had done

so with approval. As a result, two bourgeois walked along, on their way home

dealing positively with the great initiative, while a worker, on the way home in

the opposite direction after having consumed the alcohol equivalent of his wage,

appeared inclined to give shape to his contrary feelings about the subject in a

corporeal fashion whereby he - and his state may allow us to understand and

forgive this - overlooked an officer on duty charged with the maintenance of

public order standing in the background, but moreover, on approach of the said

officer, swiftly changed his target and landed his fist on the chin of the

profoundly loyal state institution, and so at a speed well above that required

to tear skin ... to make a short story even shorter, two more officers hurried

to the incident, the worker, on the ground already, engaged in prolonged and

fierce resistance, at which, as said, Ulrich suddenly got haunted by a quality

which made him claim, right in the middle of the escalating excitement, that the

workers' alcoholic state put him beyond capacity to commit crimes or trespasses

of insult, affront or offence, and should just be put to bed, whereby,

unfortunately, either Ulrich's body language or the majoritity in numbers now

acquired by the Empire caused the arrest of our young, or at least not yet

really middle aged, promising scholar.

There he stood in front of a desk at which

an officer sat, who did not look up from his job of writing on papers and

storing them in files. Besides Ulrich, one of his three arresting officers stood

in military pose of attention. That is how it remained for a while. At a

distance, he heard the snoring of his protégé, already locked up, and some more

sounds suggesting efficiently stifled protest and the tinkling of large metal

rings sporting lots of keys.

But then things went in motion. Name? Age?

Profession? Address? He had no hope his name would ring a bell here and sadly

could not expect to be inquired for his list of publications. Instead there was

interest for his color of eyes, his length, his hair, the shape of his face

("oval") and his peculiar characteristics ("none"). But then came the profession

of the father. Member of the House of Lords, yes, that changed things a bit, but

to Ulrich's feeling insufficiently, so he lied being a friend of count Leinsdorf

and be secretary of honour of the great patriotic initiative, which even should

now be known in this shabby police hut.

The immediate effect seemed

counterproductive. He caused some shyness to the highest officer around, a

sergeant, who did no longer wish to risk burning his fingers at this case, nor

to disappoint his three still deeply indignant watchmen by sending the suspect

home, and shrewdly escaped from the dilemma by claiming that someone who not

only had insulted officers and hindered the proper execution of their duty, but

also claimed to be a high dignitary should immediately be forwarded to the

Police Presidency.

At arrival at the Presidency the meeting

room light were on, there was an urgent meeting of the leadership. At the

building's reception Ulrich got the impression that the futility and lack of

interest of the case got immediately recognized but one deemed it unfortunately

impossible to drop the case there and then. Some discussion arose behind the

scene, Ulrich's shabby police hut file got read again, and curiously enough, a

broad smile appeared on the face of Ulrich's judge. He jumped off his chair and

disappeared, returned after ten minutes and said: "Herr President would

like to speak you personally".

"A misunderstanding Herr Dokter", the

president said, "I have been informed about the incident and ...", here he

started to look a bit naughty, "I am afraid I have to sentence you to a small

punishment ...", and there he waited a bit to see if Ulrich would get the point.

But Ulrich did not. The president continued: "... His Serene Highness ...", and

he paused again, looking at Ulrich, "only a few hours ago count Leinsdorf has

inquired about you in a most pressing fashion! ... And your not in the address

book Herr Doktor". The president said so jokingly in a voice as if he read the

charge.

Ulrich bent with a controlled smile.

"I do assume that early tomorrow morning you

will visit His Serene Highness in a matter of public interest, and please do me

a favour and do not repent your intentions".

The next morning His Serene Highness

appointed Ulrich to the function of Secretary of Honour of the Great Patriotic

Action.

41. Rachel and Diotima.

For quite some days now, Diotima's

excitement had grown: she had been preparing for the constitutional meeting of the

Parallel Action. This was the day. She had done everything so in the morning she

could sleep a bit.

The dining room, dining hall one should call

it at the Tuzzis, was transformed into a meeting room. Small furniture was taken

away. The table was extended with other tables. Rachel had covered their total

surface with a green cloth, without any fold to be seen. Official government

writing paper had been brought and distributed over the places, at each chair

there were three pencils of different hardness. One of those modern pencil

sharpeners that automatically loose resistance as soon a the point is sharp, had

been brought by a boy of the ministry yesterday.

Rachel was looking forward to the advent of

the nabob and judged this day solemn enough for him to take his negro boy Soliman as well.

After a last deep check it was Rachel's time

to awaken her mistress.

Rachel was now nineteen years old. Her poor

jewish family had expelled her after a young man had succeeded to seduce her to

the evil. Pregnant, lonely and desperate she managed to reach Vienna, though she

did not know why that had become her travel destination. And a miracle had

happened. Diotima had adopted her in her household, and had thus become the

object of almost religious veneration. Rachel's little daughter was now one and

a half years old, in the care of a foster-mother whom she brought, every first

Sunday of the month, a substantial part of her wage, when she came to see the

girl.

Veneration. Softly she touched the sleeping

hand and held the slippers out for the searching feet. Then to the bath,

bringing the water on the proper temperature. Let the soap foam. A last

discussion about the pencils, and the proper chair to give His Serene Highness.

When she was allowed to dry Diotima's statue-like full body as if it were hers,

Rachel felt filled with moral significance. And, as if this was not enough,

Diotima said: "Rachelle, we might be making world history in this house today".

Thus Diotima got armed for the big day.

42. The great session

Count Leinsdorf had limited the invitation

to the governor of the State Bank, von Holtzkopf, baron Wisniecky, some ladies

from the highest nobility, some prominent representatives of the charitable

world, and, faithful to the banner "property and learning", some representatives

of the university, art clubs, industry, real estate and church. Most of these

circles had sent discrete younger people fitting in this upper class environment.

His Serene Highness had been so restrictive

mainly because of those frightful zoo noises that had prompted him to his

desperate search, with involvement of the Policy Presidency, for Ulrich.

Through the key hole Rachel saw the

sabre-knot of general Stumm von Bordwehr, sent by the Ministry of War, though

it had not been invited, since, as one courteously had written Leinsdorf, "one

did not wish to show negligence to this high patriotic occasion".

But Leinsdorf surprise peaked when he was

introduced to that reform Prussian that his friend Ermelina had dared to propose for the

function of secretary of honour of the great initiative as an alternative to

Ulrich. What was this man doing here? And why had she not discussed it

first? This was the very first time Leinsdorf had to wonder about the

tactlessness of his bourgeois friend.

Leinsdorf kept his sway, but Arnheim, who

had not expected to be a surprise to Leinsdorf, got gripped by irritation as a ruler

missing his red carpet at reception.

Diotima's face stood red and inexorable as

that of a woman in her own house when she deems herself morally impeccable.

She was already in love with Arnheim but due

to lack of experience with such feelings she had no idea of it whatsoever. She simply opined

that the treasure of feelings harboured by Austrian culture and history could be

enhanced by Prussian spiritual discipline, that in general the Austrian year

could only succeed if it would not restrict itself to Austria in the strict

sense but would become a true World Year etc. etc.

Arnheim did not sense it exactly as it was,

but he was not far off, which made him reconcile himself with the incident.

Diotima opened the meeting and the word was

Leinsdorf's. His speech had been finished already days ago, he only had to skip the most

notorious allusions to the Prussian breech loading gun, which, new at the

Prussian side in the German-German war of 1866, had turned Austria, that

otherwise would have been militarily superior, from an ... - he had not planned to

say "leading German state to hinterland", but yet this section of the speech had

to be modified by improvisation - ... so now the coming jubilee year would

provide the opportunity to show in peaceful manner that despite all this bad

luck Austria should not be thought light of.

Ample considerations had made him decide to

talk about his fatherland as "a rock". Earlier speech drafts sported, in order

to comfort the Hungarians, "two rocks".

Another passage followed that His Serene Highness

decided to modify à l'improviste: "the ignorance in the foreign world

concerning the Austrian condition ..." and the wish to contribute to "good

international relations of mutual respect and esteem for each other's power".

Diotima grabbed the word to clarify the

words of the chairman. "We must ... find a great aim ... that rises from the

middle of the people". And she opened the discussion.

After a painful silence a professor took the

floor to give a survey of the general state of the world, which showed, in his

opinion, clearly what a happy moment this was for a patriotic action to start.

Another silence. Even the prelate assumed an

air of inconspicuousness.

This time the representative of the Imperial

Civil Chancellery saved the situation by starting to read a long list of

organisations, under which a nodding of approval and mutual eye contact could

fortunately be resumed.

The representative of the Ministry of

Culture and Education now judged the moment had come to report the extraordinary

enthusiasm he had noted in his ministry for the production of a monumental work

Emperor Franz Josef I And His Time.

Stimulated by this Frau Fabrikant Weghuber

proposed a "Great Austrian Franz Joseph soup kitchen".

After some more general nodding of approval

of these proposals Diotima hastened to announce the pause.

43. Ulrich's first encounter with the

great man. In world history nothing irrational happens. According to Diotima,

"true Austria" is the entire world.

Pause.

Arnheim stood next to the man from whom -

though neither of them had the faintest idea of it - he lost the race for the

post of secretary of honour of the great action and immediately was of the

opinion that the

organisation should be kept small if one were to force an entire people to

reflect on will, inspiration and essentiality, for it all goes beyond reason,

didn't it?

"Do you think it can succeed?", Ulrich

asked.

"No doubt, for are not events the expression

of a general state of things?". The simple fact of this event here, today,

according to Arnheim proved its necessity. "In world history nothing irrational

happens".

"But do not many such things occur in the

world itself?", Ulrich asked?

"In world history never". Arnheim was

visibly nervous, but this might partly be explained by his view on Diotima and

Leinsdorf and his ease to guess that the subject was Arnheim and Prussia.

He was perfectly right: Diotima claimed that

True Austria was the entire world and smothered with pacifistic fervour

Leinsdorf's last reservations relating to the reform Prussian by appealing to her

female tact and insight.

Arnheim stood concentrated, prepared for the

smallest sign he could join them, while the rest curiously crowded around him

and Ulrich, who continued: "Rationality is in those thousands of specialized

professions that arose. If now you would set all the professionals to trace

general humanity again, they simply return to the old stupidity, money and ...",

he wanted to say 'superstition' but swallowed it and said: " ... religion".

"Indeed, you're right, religion", Arnheim

said, loud enough for Leinsdorf to hear, for being a Prussian and a jew he knew

in his disadvantage, but he deemed his catholic sympathies a trump, "Do you think

is already has disappeared, root and branch?"

It seemed that Diotima and Leinsdorf had

reached some kind of accommodation on the issue of Prussia. They appoached. The circle of the curious

dissolved politely, and suddenly Ulrich stood alone and sank into deep thoughts

about Pepi and Hans, the two horses of Leinsdorf's coach that he had been

introduced to when leaving together for the meeting.

In that coach Ulrich also learned that Stallberg

had informed Leinsdorf that his confrontation with Ulrich's "fire" had been