Robert Musil

Der

Mann Ohne Eigenschaften

First Book Chapter 75-101

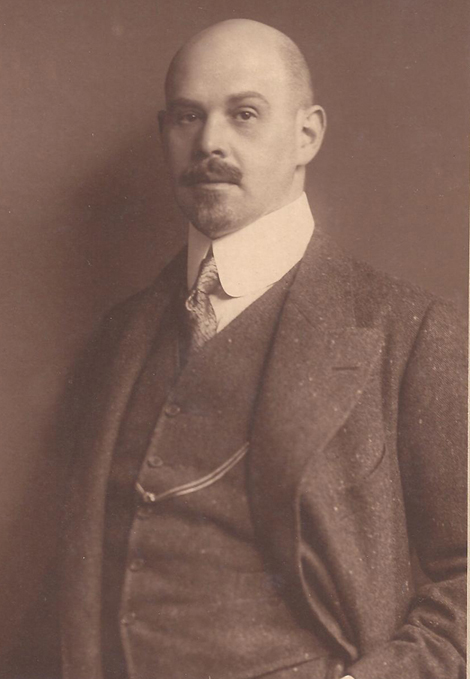

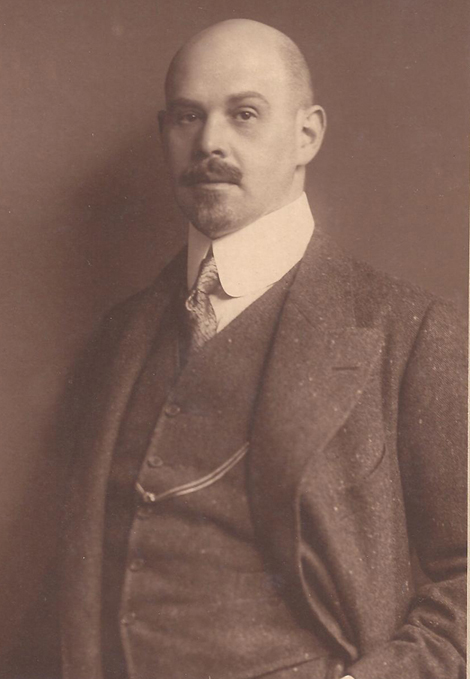

Walter

Rathenau

Crtd 15-04-29 Lastedit

16-08-18

download pdf

Robert Musil

Der

Mann Ohne Eigenschaften

First Book Chapter 75-101

Walter

Rathenau

75. General Stumm von Bordwehr considers his visits to Diotima a beautiful diversion of his official duties

Little fat Stumm had enjoyed his visit to Diotima. After a while he decided for another field day. Once on his chair, he unfolded his vision that only military power, though understandably not high profile in this initiative, was capable of maintaining peace.

"General", Diotima said, trembling with rage, "all life is based on the powers of peace, even business life fundamentally is a poem!"

Puzzled, Stumm lowered his head, but quickly sat upright again and said: "Your Excellency" - for in terms of army ranking Tuzzi would be called so, and out of politeness his wife as well - "of course War could not have its own committee in this pacifistic initiative, but you should know how we like such things - an international peace initiative or the donation of some paintings from our fatherland to the Hague Peace Palace? - you see, there are so many misunderstandings about the army ... I ... do not wish to deny that every now and then I see the odd young lieutenant wishing war, but the leadership has always been deeply convinced that the sphere of violence, that unfortunately is our hallmark, should be connected with the blessings of the human spirit, just like Your Excellency just expressed herself."

He took a little brush from his pocket and started doing his beard, a tic, it seemed, but kept gazing at Diotima with his big brown eyes.

Her rage resided.

And then Stumm started praising the order of spirit, "Geist", from a general theory of the order of things.

Diotima listened. She had no clue what to say herself and finally said that on short notice she would convoke the the greatest minds of Austria, for keeping order in all that got on her path in setting up the Parallel Action had been a challenge indeed. "But never could we", she added, "reach our goal by an act pure ordering. A flash, a fire, an intuition, that is what it should ultimately be. History may seem a logical development but its twists and turns remind me more of poetry".

"Please do not take it ill of me, Your Excellency", the general answered, "the soldier knows little of poetry, but if anyone should be able to provide flash and fire to an action, it surely is an old officer!"

76. Clount Leinsdorf sports reservations.

Something had occurred in His Serene Highness' mind that discomforted Diotima. His interest seemed to have shifted from the spirit of her elitist salon - and this transpired from the new expression "mere literature" he started to frequently employ - to that of the pastures, the farmers and the village churches of his fatherland, in other words, to, as it were, the cadastral register of spiritual legacy. To shape the festivities, he now thought one should primarily know how one thought in milk cooperations, hunting clubs and the like.

Diotima expressed to Arnheim her regrets about Leinsdorf's shift, but, Arnheim's love of the simplicity of the heart made him take His Serene Highness under protection, though he could not resist suspecting that Ulrich's ironic view of the flood of spiritual matter triggered by the announcement of the "Austrian year" could have had some influence on the count. "He is a charming but dangerous person by his combination of juvenile moral exotics and his trained mind, constantly seeking adventure without knowing why".

77. Arnheim the media star.

Diotima regularly got the chance to see Arnheim's simplicity in operation. On his advice journalists had been called in.

After his slightly unhappy appearance at the first official meeting Arnheim had restricted himself to receptions and avoided deliberations completely, but when journalists appeared, he turned out to be seen as the centre of the Parallel Action without further ado.

An icon. Without any effort. Like flies on the shit. His preposterous nonsense, especially that dictum that 'the sole rise of this initiative proved its necessity', went down like manna from heaven. Frantically nodding they all copied it in their little notebooks. Several journals featured it prominently. There were plenty of great minds that evening but when Arnheim spoke to journalists they heard the general spirit as a matter of fact.

And among all those great minds Arnheim did well too: they were pleased by his confidence-keen slightly pessimistic modesty in which he said that expectations should not be too high. That was generally preferred to a colleague managing to unexpectedly shine and steal the show.

78. Metamorphoseis of Diotima.

Diotima's feelings did not rise as rectilinear as Arnheim's star in Vienna.

She did experience the occasional euphoria thinking of the growing reputation of her salon, especially now Arnheim's presence and weight had given stability to the intercourse and thus had taken away her nerves. Sometimes she looked at him while he was talking in some corner, then realized she had done so all the time but only now got aware of it.

And she could profit from his lessons in politics, for now she understood why the Austrian elite around her tended to scorn Germany but curiously enough, by way of brotherly obligation uttered itself in contrary direction when dealing with the French-German rivalry. This turned out to be a Gallic-Celtic-Ostic-thyreological problem connected with the Lorrainian coal mines and thus in the end with the Mexican oil fields and the contrast of English and Latin America.

Those were issues totally beyond her husband Sektionchef Tuzzi - or he pretended ignorance about it. Tuzzi kept loudly asking himself in her presence what would be Arnheim's real intentions to play his suspicious role here. Thus Diotima got even more deeply convinced of the superiority of the new people over the methods of obsolete diplomacy.

She still considered her decision to bring Arnheim in the top of the Parallel Action to be her first great idea. Its conception had come with a miraculous state of dreaming in which all things that thus far formed part of her world simply had melted.

What a good decision had it been! For, to be honest, for the rest the Parallel Action had yielded failures only: a competition among the greatest of minds in producing useless ideas, and Leinsdorf's zoo noises, so neatly codified and archived by Ulrich. For the rest one thing only: Arnheim.

Improvidence, joy, not rarely reaching peaks in ecstasy, even triggering daring jokes, and resulting in plan lists too large for her schedule, as a result of which she occasionally could start the way an archduchess painting flowers - since for someone like that there are no other decent subjects - does when suddenly confronted with her immense stock of self made flower paintings.

Before this new life, had you woken her up in the middle of the night to ask about the essence of life, she would have said that the living soul should express its power of love to the world, and waking up a little bit more, regaining awareness of civilization, she would have spoken about something "analogous the the power of love". For in those times she still divided herself in little drops of love that she tossed away, after which she got left with the empty bottle of her body that belonged to the inventory of Tuzzi's house.

But now the power of love had firmly regrouped in her own body. She had awakened by the thought her nephew had inspired her to, that she was on the verge of a Deed relating to Arnheim.

Her husband got confronted with this excitation, wild fun may be just a slight overstatement, in a rather special way. Her underwear got naughtier. Every now and then he got embraced in such a passionate way that he felt relieved when it was over. He got given a hiding for 'plunging' on her in the act of love 'like an animal'. He hardly managed to keep up with this revolution in the domestic part of his life, but the generally admired success of his wife had even pressed out of his conscience all options of dominant action or sharp ridicule.

Tuzzi read Arnheim and hated writing men as the cause of his suffering.

For Tuzzi's explanation of the phenomenon of writing was 1. boredom (the retired government officer writes his memoires), 2. dissatisfaction and ambition (one hopes to be heard where in one's own environment nobody listens - this in Tuzzi's mind included jews), 3. remarkable adventures (but only at old age and abroad), and 4. money (where he could even find justification for someone whose name had acquired poetical branding). But this Arnheim, why did this man write so much. Tuzzi was painfully aware to have no clue.

79. Soliman loves.

Soliman the little negro slave, or negro king, now wanted to involve Rachel in his noble mission to guard the entire house and prevent Arnheim's dark plans. In the proper negro king's oath both parties put their hands, opening a few buttons, on the other's bare chest but Rachel refused. She had acquired a taste for espionage though. It rose sentiments like bashfulness, veneration and admiration. So, when no one looked, she squatted to look through the keyhole, and Soliman stood behind her, holding her shoulder just to prevent loosing his balance.

Soliman flatly refused to help Rachel serving the guests and sat in the kitchen waiting till she was done. If that took too long he escaped in quasi-stealth from the cook and sneaked through the corridors looking for her. He was good at surfacing before her at the most unexpected of places. Once Diotima had caught Rachel spying Arnheim and her and, outraged, sent her to her room. On her way there Rachel had already looked around for Soliman, but failed to see him for he was in her room already.

Rachel hesitated closing the door, but Soliman quickly relieved her from that job and said: "Give me your hand!"

He had a couple of cuff-links and tried to fix them on her sleeve.

"Gems", he proudly explained.

This was fishy, Rachel decided. Quickly she pulled her arm back. She thought of saying something like: "honesty is the best policy", but she rejected the option. Too simple. Pressure built. Then she said: "I do not steal from my house!".

"Why not", Soliman asked with all his white teeth.

"I just don't do it"

"I did not steal them, they are mine!", Soliman protested.

He grabbed her arm again, she resisted, he started to pull in rage but was no party to her, lost and bit her in the arm like an animal. Rachel got a scare, her fist landed on his cheek and he collapsed in a tantrum hiding his wet face in het skirt, she felt the tears dripping on her thigh. That was something new to Rachel and it came so unexpected that her fingers started to softly caress his frizzy hair.

80. One gets introduced to General Stumm, who unsuspectedly reports at the council.

The meeting of the main committee of the Parallel Action, in the meantime baptized "the council", had undergone a curious enrichment in the form of the unexpected appearance of General Stumm von Bordwehr, showing his feelings of honour, excitement, and gratitude for having been invited.

Over his head Diotima scanned for the possible suspect. Arnheim of course was absent and Ulrich stood near the pastry, looking extremely bored. She felt totally sure that someone like Stumm would never do this without an invitation. The cards left over were in a drawer in her writing table. Supernatural forces? She believed in them but this would be a stunningly concrete case.

Stumm had wondered as well, address and beginning were not totally correct and it had clearly not been the hand of Madame Her Excellency in person, but he was a cheerful man who did not enter into suspicions easily, surely not if they would involve the supernatural.

For Major General Stumm von Bordwehr it all began, a few months earlier, as follows: the Chief of Ministry of War's Presidium Section had called for him and said: "You are such a kind of intellectual, Stumm, we write a letter and you just go there. Just keep your ears open and tell us what they want to do".

Stumm knew that his assignment involved making sure to get on the list of regular invitees, but this had failed despite his two visits to Diotima. Reluctantly he had confessed this to his chief, after which he could storm back in the man's room crying victory.

"Do you see", Fieldmarshal lieutenant Frost von Aufbruch said, "I never doubted it, sit down". The doorlight got switched to a red lettered "no entry, important meeting", and he continued: "We do not want anything special, you see, we don't care not to have our own committee, but we simply cannot fail altogether when a general spiritual gift to our emperor is prepared, that is why I take you, then no one can have anything against it. Go ahead!"

Delighted, Stumm had clapped his spurs.

Let's face it: everybody knows a few bellicose civilians, how on earth could we think that there would be no peaceful servicemen? And indeed there are many. Painters, stamp collectors, amateurs of history books. Stumm had failed in cavalry due to lack of grip and authority over the animal, got moved, grew a full beard, daring, but not prohibited, and became a collector of pen knifes (both with and without cork screw). They had found him a job as a military teacher. As usual, one rank followed the other, whether in the evening you fuck before you drink yourself under the table, or, as Stumm did, the other way around, and when high up in the ministry the chief of military education retired, a former teacher remembered his old colleague Stumm, they made him general, and it would be odd if he would now not end up as fieldmarshal lieutenant.

His full beard for long was replaced again by the usual side-whisker shrubs, but now he got bold, all in all (remember his belly), quite an intellectual appearance from a military perspective.

His craving for the non-military emanation of the married warrior had made him take a wife, and only after he got two children as well, he started to realize the rationality of his former life style, remembered a heap of photographs of beautiful ladies, collected in his youth, thus rediscovered his original view on the woman, and attached it extramaritally but platonically to ladies evoking his shyness - so it would not create any further disorder.

And this had led him by an invisible hand into this room of the council of this gorgeous Diotima!, Stumm thought in the best of moods. His little arms felt far too short to span Diotima's full circumference, neither would his mind be able to fathom hers as far as The World And Its Culture was concerned but who cares! His round belly felt like the globe itself.

Diotima had already given him an angry glance for staring at her from a distance, and he just had engaged in settling for a decorative position along the wall when he spotted Ulrich - still, and still with the same facial expression next to the pastry - and realized this was the thoughtful restless lieutenant that had formed part of his horse regiment for a while.

"An excellent opportunity for me to get acquainted with the main civilian questions of the world", Stumm said.

"You will not believe your ears general", Ulrich said.

The general shook Ulrich's hand warmly. "You were lieutenant in the Ulanenregiment", he said, "and that will turn out to have been a great honour to us, though our old brothers in arms will not yet realize it!"

81. Count Leinsdorf on pragmatic policy. Ulrich founds associations.

No hope at the horizon in Diotima's salon-council but in count Leinsdorf's palace things acquired pace. Associations reported. Land-, water-, moderation- and drink associations, singing and football clubs etc.

You'r Serene Highness, Ulrich said, flabbergasted, "how on earth can it be that in an orderly state everybody belongs to at least one gang of robbers!"

"Yes, yes, and those are our handles", the count said, "no ideological fuss but pragmatic policy. This grandiloquence at your niece's is not without danger for our action".

"Does Your Serene Highness have directives?".

The count looked shrewd and said: "We should not do what they want. It already in Kant."

"Indeed!" said the pupil in surprise, "but don't we need some target?"

"A target? Bismarck's was to boost the Prussian king. This turned out to require war with Austria and France and the foundation of Germany. You can put a people on its feet but then it should walk. And those legs are its institutions, parties, associations, clubs et cetera, and not what everybody is babbling about.

"Your Highness! That is, though it might not sound so, a truly democratic idea".

"Well, yes, maybe aristocratic as well, though von Hennenstein and von Türkheim keep telling me it will only result in piggery, so be careful, be nice to everybody reporting!"

And they came. Ulrich received a stamp collector, and analyst of signposts and headers who had discovered that three letters each of them with four straight lines (e.g. WEM) had the smoothest relation to the human brain and that the use of especially O, S and C should be discouraged, advocates of mental arithmetic, of stenography etc. He recommended whomever did not yet have and association to found one, for it would have the support of the count. Other requests he told he would put to serious consideration: a football club sollicited, in the interest of boosting contemporary body culture, the title of professor for its mid-half.

All went into his orderly database.

Leinsdorf, in dealing with border issues and anecdotes, turned out to have learned from seeing Arnheim operate: something is something when people think so. Wait and stimulate.

82. Clarisse demands an Ulrich-year.

Early afternoon seemed Ulrich the best time to see Clarisse. Walter would be jealous but on his job.

"I come to tell you never to write such a letter to Leinsdorf again".

"Never tell Walter, but tell me what's wrong with it. Wouldn't it be marvelous, a Nietzsche year? What did your count say?".

"Well what do you think, with that Moosbrugger in it. But he would have thrown it away anyway".

Clarisse looked disappointed, but after a moment said: "Well fortunately you are there to correct him".

"I told you you're crazy".

That visibly pleased Clarisse, she grabbed his hand. "Don't you think that entire Parallel Action is nonsense?"

"Of course".

"But a Nietzsche-year would be nice".

"How do you imagine it?"

"That's your business of course".

"You're a nice joker".

"To propose you to finally do something serious? Why?"

Ulrich pulled his hand loose. "Well, then why Nietzsche. Could be Christ or Buddha".

"Or yourself, make an Ulrich year, you!"

OK, so she had no vicious intentions Ulrich thought.

"Do it! But don't tell Walter".

"A coup d'état?".

"OK do a Buddha-year. I know little about him but if his ideas are thought important, then take him".

"Now listen. Suppose we do a Nietzsche-year. He is on your shelves for years. What to do?"

Clarisse started three or four times, stopped again and finally said: "Why should I tell you, you know that much better than me ...".

"I ab-so-lute-ly know nothing at all. Except that the best ideas are the worst to realize. Soup kitchens and dog clubs, those are things you can work at. Why is this so? No idea. But it's like that"

Clarisse continued but he looked at how her thoughts seemed to come out of her body as a whole. Everything moved when she said something. Hard, thin and boyish as it was she yet looked like a Javanese dancer. A splendid unity of body and mind, as he himself totally lacked.

"Ideas", Ulrich started to lecture, "are only like a talisman for people. It brings luck if you carry them. Every now and then you touch them. Gives you power. But they are made of quickly decomposing material. In no time bacteria start to destroy them. quickly the get smelly. Fortunately fresh ideas are freely available everywhere".

But after an unclear moment in his head Ulrich defined the idea as "yourself but in a special state, as an oscillating string making a tone, something that at first seems to generate an infinite stream of beauty but after some time walks, like a soldier, to its proper place in the platoon to freeze."

"Walter is jealous. Not because of me but he thinks you could do what he would want".

Walter, Ulrich thought, had done too many things. It all got connected and now he is caught in its web. Connections deprive experiences of their personal taste. Bad as well as good taste.

"He has to kill you I told him", Clarisse said.

"What?"

"End your life. Des-troy. If you are so worthless as he claims you are and he is so much better, and if it would give him peace he should do it. I said. After all you can defend yourself".

"That's not a bad thing to ... " Ulrich hesitatingly started to answer.

"Well, that how the conversation went, what do you think? Walter says you should not even think about it."

"Well thinking, why not?", Ulrich said. Clarisse had a unique charm. Did she stand next to herself? She was there and not there, but the two were very close together.

"You and your thinking", she interrupted, "you are as passive as Walter. But my opinion is that if you can think something that means you can do it".

"Yes but there are two types of passivity: passive and active".

"Then what is the active?"

"Like a prisoner, waiting for the opportunity to escape"

"Only pretexts!"

"Well, ... maybe ...".

"The most immoral thing", Clarisse said, "does not come from mean people but from those others who let it happen".

83. And thus it happens, or why does one not invent history?

What could Ulrich have said?

He had stopped short of saying that God never meant the world literally. Its more a puzzle for us to solve. Would she have agreed to see life as a kind of Red Indian or robbery game? Sure. If one would take the lead and go she would push him aside and take over, like a wolf, nostrils wide.

Or think of a bunch of mathematical equations that have an infinite solution set. One isolated moment or period of mankind gives no clue, but the more you have, the narrower the solution set gets.

On the way back in the tram his fellow travelers made him feel ashamed about his lack of clear plans. You could just ask all of them: what are you going to do? Even for high flying thoughts nowadays there were orderly bird breeding institutions, like philosophy, theology, literature ...

He had no doubt the progress in the division of labour was unavoidable, but though he was nor aspired to be a professional philosopher he insisted on the frivolous action of thinking personally. Old fashioned. A ant hill works so well because nobody there deals with the thing as a whole.

Did we have a Balkan war or didn't we? Jouhoux had just brought the record flying height on 3700 meters, Johnson now was world champion boxing. A negro. The president of France was in Russia. According to German newspapers this was a threat of world peace. 1913-1914, an eventful period. Just like any earlier period. And how did those earlier times end up in our times ... a machine shaking people and throwing them over the earth's crust to see what happens. Would he become part of that? No way!

Hundred years ago in the post coach, now in the tram, in hundred years in some future machines, but people will sit in them in the same way.

He urgently had to leave the tram. But he hadn't yet arrived. Walking, he mapped out why Clarisse's (and Diotima's) idea of a year of the mind was so ridiculous.

1. World history is the result of historians successively copying each other.

Digression 1: if in Ulrich's horse regiment the exercise of transmitting forward was practiced of the message "Fill the ranks straight and ride" what reached the front was: "Kill the man to your right".

2. The difference between a cannibal and a philosopher is grossly overestimated, as well as misidentified.

3. Recreating and restarting Egypt 7000 years ago, would first show replication but gradually start to diverge.

Digression 2. History is wrestling on.

4. (or digression 3?) It is not a billiard ball but a cloud.

But now he really was in the wrong street. What would be the shortest way home from here? For a while he had no time to consider it for indeed history should be made, invented, she was right, but then why isn't it done?

Leo Fischel would say: "Your worries in my head".

No no Leo, Ulrich thought, it isn't as simple as that. I say history, but what I mean is life, which extends beyond getting wounded and seeing things getting on fire. Not only the emergency situations marked "history". But Leo believe that a kind of balance of power, an armed peace between ideas is the best. Such a stability allows us to relegate the matter to scholars, who keep it at bay so we can go to our jobs every morning, and do what we always do: creating chance.

And that ended the Ulrich year, for he had reached home ...

84. The claim that common life is utopian as well.

... where he found the daily bundle of mail from Leinsdorf. Ideas, quarrels about ideas, founding of associations, requests for funding, etcetera.

Etcetera.

He pushed it aside, called for hat and dress-coat and said he would be back in an hour.

He stopped a coach and returned to Clarisse

For the purpose of formulating a program to live history of ideas instead of world history. The difference was in the reasons why you do something. You do not just follow your animal nose, but leaving behind your instinct of personal acquisition you would turn things not in your own interest but upward and outward. Such should every individual do, but society as well. It would be like pressing and storing mental juice. The result would be the abolition of reality, just as he had told Diotima.

Well, little need to say Walter, after Ulrich's arrival hearing it, had no difficulties. Did not things go like that for ages?

But Ulrich said the juice thus obtained was accidental. It selected only ideas that happened to come up and rule. His type of juice, however, should be made void of self interest and as if nothing preexisted!

"You talk as if we have a choice", Walter said, "between the life of ourselves and that of our ideas, don't you know that saying: 'I 'm not a neat nice phantasy but something real annoying me'? Shall we abolish our bellies as well? We'll never be hungry."

"Yes we should" Ulrich said, "our life would be entirely literature".

"Better canned food than real?"

"Something like that", Ulrich said, "or that I would want to cook with salt only". He wanted to end the subject.

But Clarisse had not finished: "Nothing pleases you when you are the only one experiencing it. And mustn't there always be something in it that is new to you?"

Walter was fed up but thought he should support Clarisse: "If only the mental effects of action count, you are building up mental power and force."

"The aim of all states", Ulrich said.

"And should those people in those states make philosophy and literature or realize it? If they make it, that would be nothing new, if they realize it, they make art superfluous".

Ulrich hesitated, then said: "Isn't every perfect life the end of art? Aren't you abolishing your art to render your life perfect?"

He did not want to be mean, but Clarisse was surprised.

Ulrich continued: "In art you always have ambitions that do not match reality. Just add that up and you have the ultimate mismatch".

That was not Walter's style, this idea of art as a protest. Bohemien, young adults, bourgeois teasing.

And Ulrich knew he was now covering only a part of the issue.

"Well" Walter said, "in that case I ask myself what a man does if at some moment he fails to be the poet of his own life. Back to the animal instinct? Or just follow your hunches until you find the next good idea?"

"Then he should refuse to do anything", Clarisse answered mockingly on behalf of Ulrich, "That is active passivism, I just learned".

Ulrich heard the echo of Clarisse's "Pretexts!", but Walter's head got knocked the other way by her word "refuse", since refusals dominated their relation at the moment, and seemed to be decorated with Ulrich's "active passivism". He turned grey.

Ulrich saw it and aked whether something could be done for him.

"Stop the nonsense", Walter said, for whom the discussion had looked bright for so long before ending badly.

85. General Stumm's ardour in bringing order in civil understanding.

When Ulrich arrived back home it turned out to have lasted an hour longer.

There, he was informed that a military officer was waiting for him for quite some time.

It was general Stumm von Bordwehr. "My dear friend, I have to apologize for disturbing you so late, but I could not leave the service earlier and moreover I sit next to your alarming collection of books for two hours"

Stumm went down to business at once: impressed by the civilian discussions surrounding Her Gorgeous Excellency Frau Tuzzi, he had tried to map the world of civilian ideas, which had failed so massively that now he urgently needed, "well, I'm always saying nothing is urgent except the visit to a certain place, but, to be serious ...", help.

Stumm did not have a low estimation of his capacity to order, ... Ulrich, he asked, knew as a former reserve officer cadet of Stumm's horse regiment, the Ulanen, as well as he, Stumm, that when a soldier does something, he does it, and neither was Stumm stupid, or was he? "So you agree and I can talk to you in confidence: I am ashamed of the military mind. It is like a provisional report, you know: how much food, men, horses, state of health, but nothing about what explains the situation. What has the soldier and of which? We teach the newcomers to answer: two pairs of boots of which one pair under the bed. But why? And that is what the gentlemen of the civil I so often get sent to want to know and there I stand again not knowing what to say, you get me? Interrelations of higher order."

"Now I proposed my chief His Excellence Frost, or rather, I want to surprise him with it, to use my happy intercourse at present with the civilists, to do a thorough reconnaissance and map everything. We have specialists in the army in all fields, but civil mapping, that's just not yet there."

Only now Ulrich saw the sizeable briefcase Stumm had positioned leaning against a leg of the table. With some strain Stumm pulled it towards himself and opened it's decisively military, heavy metal lock.

"As you see, I have not been idle", Stumm said, "but there are a few things that I failed to get in place".

"From your niece", he continued, pulling some sheets out, "I understood that we should surprise our highest lord the Emperor with the highest idea of all, and we are now searching for it. But in doing so I got into damned problems. One says this, the other says that and thus civil understanding reminds me of a bad eater, you will remember what that is, such a horse you can feed anything but it won't get any thicker."

"Well just thicker you might manage but ..." Ulrich said helpful.

"Yes, I mean", the general corrected himself, "it will get thicker but simply by getting this grass belly and bad dry skin, the joints stay small, well, you see that has my main interest now, why order cannot be brought into the matter".

"Here", Stumm handed over an impressive scheme, "is the consignation of main ideas I'm given there. But everyone puts another one on top".

Flabbergasted, Ulrich's eyes scanned the scheme. A grid in the format of a military survey. In martial calligraphy he read: Jesus Christ; Buddha; Gautama (or Siddhartha); Laotse; Luther, Martin; Goethe, Wolfgang; Ganghofer, Ludwig; Chamberlain, .... Second column: Christianity, Imperialism, Age of Traffic, .... The edges of the paper left no doubt whatsoever that below and to the right other papers could be put in which the rows and columns were continued.

"You could call this the leaf of cadastral layers of modern culture", Stumm modestly said.

Answering Ulrich's question how he had achieved this: "I fielded a commander, two lieutenants and five under-officers. We could not do a poll to select staff, for that requires involving the top. Just relying on book knowledge is unfeasible for then after the Bible you get the New Year's book of the Post with the tariffs and old jokes, moreover, as I am now aware, in the civil world you are not an exceptional mind unless you have a huge lot of likeminded people. But somehow they managed, using an idea of Corporal Hirsch, in cooperation with Lieutenant Melichar"

Stumm took another leaf, while his face grew dark. "Here you see", he somberly told, "how those oppositions of great minds are fuzzy to such an extent that they are basically all saying the same. Not very helpful either". On this sheet common terms and assumptions were listed of individualism and collectivism, nationalism and internationalism, socialism and capitalism, imperialism and pacifism, rationalism and superstition. "In these cases", Stumm said, "I feel like seeing two electricians forging a huge network in peaceful cooperation, and only when the job is done they start quarreling about how to set the switches".

This would have surprised the general as little as limbs having a stretching and a bending muscle, were it not that his ambitions were motivated by his platonic admiration of a high standing beauty involved; for love hates quarrels, especially when, as in this case, the object of love continuously, pacifistically and grandiloquently confides her fucking hate of it.

"This" Stumm pointed at another paper, "Is a list of commanding ideas, all names that, so to say, gained ground with large divisions, then here is the ordre de bataille, and here ...", Stumm took another sheet, "the plan of attack". Then he showed a survey of depots and weapon storages, used to retrieve later defensive and offensive thoughts. But those are frequently taken by the enemy and brought into contraposition, their personnel included, and this, you know, is what makes the front and its movements so confusing. Entire ideas desert and go over.

"All in all", Stumm said, "what they are in need of is a stage plan and clear lines of demarcation. The whole thing is, with all respect - I really cannot myself believe what I am going to say - a piggery".

Stumm dropped a few handfuls of papers on the table. Plans of advance, road lines, street networks, portéedrawings, troops signs, command posts, straight angles, shaded boxes; like in a professional survey presentation for general staff red, green, yellow and blue lines ran through each other, and colourful flags, each with their own meaning, as they would become so popular just one year later.

"Of no damned use at all", Stumm sighed, "I've even tried to transform the whole thing from strategic to military-geographical, for I thought may be I at least identify the space of operations. Forget it! Look, here you have the orographic and hydrographic versions".

Ulrich saw mountain tops from where lines branched out that came together elsewhere, sources, rivers and lakes.

"I have tried things that I'm not even going to explain! The bottom line is this: lice!! A second class train wagon upcountry, the kind of place where things start itching you everywhere, no rest, even if you scratch yourself until you bleed!

Ulrich had to laugh.

"Now don't laugh for a moment. This is what I'm thinking: you have become a prominent civilian, you understand these things, and you understand me too, so please help me, I have to much respect for the great civilian ideas to believe I am right!"

"You are taking it far to serious Oberleutnant". That had been Stumm's rank in Ulrich's horse platoon period. He apologized quickly: "You so agreeably put me back to when in the casino you would order me to the corner to philosophize. But you take it too seriously!"

"Say you don't mean it. I start choking when I think of how long since you left I lived on that parade and in those barracks between officer's jokes and sex-boasting and now I want order in my head!"

Meanwhile, Stumm had been invited for the evening bread and they went at table.

Stumm's stayed totally focused. Each piece of sausage dangled for ages at his fork. "This niece of yours is really magnificent. I am also married, but this is of course another league. Often I admire her female fullness from the rear side while the front side is conversing with an eminent civilist in such a scholarly style that I regret I can't take my notes. And her husband the Sektionschef is totally unaware of it, just looks around with a face as if he knows where Abraham gets the mustard, and isn't going to tell us. Look, those civil officers are the lowest in the civil world, unarmed soldiers with the politeness of a cat looking at a wolf from high up a tree. No, then look at Arnheim. May be also hypocrisy, but it has a presence".

Meanwhile Stumm's wine consumption had made substantial advance without meeting any resistance. "And so it is with some relief that I note Her Excellency Miss Tuzzi is in love with him"

"Are you sure they have something?"

"Well, not sure, but I would not have anything against it. I am not gay but I do feel with the man if I think what she ... whether she really does so or only would like to. Once she took his hand and it went silent in that corner like they had commanded kneel down sjako off. Then she softly said something and he answered 'If only we found the saving thought'. And she again: 'Only a pure unbroken thought of love can bring salvation', which of course he took too personally, for she no doubt was thinking about the great action ... what do you laugh? I've always had my peculiarities and now I took it on myself to help her. And to do so I need you!"

Meanwhile they had lit the cigars. "General, you are on the wrong track. That is because you expect to find the spirit, Geist, in the civil, and the physical in the military. But it is the other way around. For thinking is order and order is military. Properly marching is the highest state of the mind!"

"Fool your grandmother!", Stumm said.

But Ulrich continued: "Science", he said, "is only possible with things that repeat themselves, such as they do in the military. The laws of the movements of planets are shooting orders, only with higher speeds and bigger calibers, that's all. Science needs events that repeat themselves, that's the problem with God for He appeared only once, at creation, when we did not yet have certified observers on the payroll".

Stumm did not let himself be wiped off the battlefield: "Good jokes all those, but we deal with the soul here and if I think of that I'd much rather stand in my bare arse than in my army uniform."

"Dear Stumm, listen! They are now seriously studying the soul and it turns out to consist of firing neurons! Conduction of electrical charge! Reflexes! Repetition! Fixation! Circuit building! You would feel at home at once: in our brains it's all barracks, battalion, uniform, rank and file, discipline, order and execution. What is the beauty of a woman? Its an inventory sheet filled out in your brains then electrically signaled to supply troops."

"Ok ok, honour to the truth, you have a point", Stumm said, "we soldiers might not think as different from the civilists as we presume, but those things that are so typically civilian from our perspective, soul, virtue, intimacy, mood, this Arnheim can talk about it like a wild beast, well, it might cause the odd post traumatic stress disorder left and right in his audience but it is flatly superior, are you going to deny that?"

"You step over my claim that Geist is essentially military and the physical is the realm of the civil".

"O not that again", Stumm interrupted. He felt no doubt whatsoever that his own round belly was far more solid than that of a civilist.

"Let me finish for a change", Ulrich said. His cigar had gone out. "Hundred years ago a civil fool in Jena thought to have proven the laws of the world as the propositions about the triangle. No paraffin lamp yet, no gramophone, no airplane. This hubris has backfired, for every time new truths got discovered, the gain in the order of detail was a loss in the order of the whole. That silly high flyer lost elevation even faster than religion".

"My research suggests the same."

"And what they lack is your ardour. If anything, they get even lazier. Look. If a man of significance brings an idea in the world, all those guys do is divide the booty. First admirers fight for what they consider good pieces thus tearing their master to pieces like foxes their prey. Then the bad pieces are destroyed by the opposition. In no time nothing is left but a bunch of aphorisms used by friend and foe, and that is what constituted the data of your mapping platoon", Ulrich said, pointing at all papers on table. He felt an urge to make a neat straight pile of them but suppressed it. "And this is why great ideas seem unclear: you don't see a tree! You see a heap of half burnt firewood that's left of it, used by all shades of minds for all kinds of purposes. As in love, hate and hunger, tastes have to differ so everybody can get what he desires".

"Excellent!", Stumm said. "I already have expressed myself similarly to Her Excellency Frau Tuzzi".

"You should tell her that, for reasons yet to uncover, God is starting an era of body culture, for the only grip for an idea nowadays is the body that has it. Tell her! As an officer you even have some extra leverage!"

"As far as body culture is concerned I am doing no better than a pealed peach and I think of her in an orderly way!"

"That's a pity," Ulrich sighed, "your intentions would not be unbecoming to Napoleon, though you would not have found the proper century". He lighted his cigar again.

The general had bravely withstood the derision, dignified, but also in pride of not stopping short of suffering for the lady of his heart.

After some thoughtful moments he said: "Anyway, thank you very much for your damned interesting pieces of advise".

86. The king-tradesman and the fusion of soul and commerce. Also: all roads originate from the soul, but none leads back to it.

Arnheim was well beyond the point where he should have decided to appoint a stadtholder for Vienna and leave for good. But he did the reverse.

It was 1913 and world politics was rumbling. "Ballhausplatz", the Austrian foreign office, Tuzzi's ministry had its lights on all through the night, discomforting every educated reveler passing. The volcano smoked, but wide public excitement still had to rise. Arnheim of course knew everything. The Arnheims had factories for armour-plate that worked on a near full capacity unmatched in history. Ammunition also produced at record level. Every day he received coded messages and every now and then he received a man from his own intelligence department, with whom he liked to meet in his hotel's lobby in order to show his importance.

But he knew his Viennese jobs were marginal and slightly overdone just because he happened to be there.

He was in love. Slightly disconcerted he observed his slight unsharpness in his dealings. A sparrow on the window-sill. A waiter's friendly smile. Those were the things his reality suddenly seemed to chiefly consist of. The wide and fine net of his moral convictions was somewhat out of the picture and what remained of it had something corporeal. No, when love throws itself on a woman it looses some of its nobility. And it gets a bit childish as well: if you do not watch out you are in the middle of a abduction phantasy. Neither is there much elevating to be found in this urge that runs up and down in the background of the soul, to release all brakes, which even tends to acquire some moral attraction as a result of the fading of concentration on daily commercial routine, as if it would be the only thing mattering.

Such things make you think of your youth more often, in which he had been an intelligent child with intelligent educators. He had been endowed with a keen sense of good and evil, for he often was rolling over the street with other boys in defense of injustice. This required a sudden and lightning fast escape from his custodians. Since he always got retrieved within thirty seconds he kept convinced that he would have won, which partly explains the pathological excess of self-confidence of the adult Arnheim.

All this he could remember well, but another experience had petrified (If you agree to keep diamonds in the category of stones). And that one, the scare goes without saying, got awoken by Diotima. The issue is this:

In his youth he had become familiarized with love independently women, of people generally, and this had left him with an unsolved problem, to which he later learned some of the most modern of explanations. I have in all modesty to confess it was me who wrote about it in "Die Versuchung der stillen Veronika". And Arnheim held me high for at the time it was a token of expertise to know me, a hidden man, as I was seen already then. But of course he had not understood anything of it. He grew in a world of tennis, visiting, flabbergasting his father, labour meetings (for he had read about socialism), after which all the same he drove on one of his horses through labourers villages in swanky outfits, but some vague romantic feeling had been whispering that there was a second world floating in the first, with bated breath.

And this was what Diotima had pulled down under inside him from its chain. His soul seemed to have risen over its shores, no longer did the outer world end at his skin and no longer his inner world stood gazing out of the the window of deliberation and balancing. Inside and outside had united as a separate entity, mild, quiet and high as a dreamless sleep. He looked the same as ever but felt totally changed inside.

Religions and the like have the habit to see such a thing as an indication of change in an underlying reality, but most of us get haunted by it in the period of our first love affairs, and so we quickly recover from it as from all other unreal experiences, dreams and imaginations. But that was Arnheim's problem: in his life there had been no personal love affairs that could have immunized him to this type of sensation.

So the experiences after his youth, notably his introduction in his father's business life, had only covered it, as a result of which he had started to see the results of his work like kind of poems, but not of the type forged by a poet who, on an attic with a pen in one hand, needs the other to keep the flies at bay, no no, poems created in the material of life itself!

This had kept him in the grip of a mission, a call for syntheses of ... and so on and so on, things which his fellow tradesmen, just normally quarreling with their wives as everyone, had to laugh about. Not that such things were altogether unknown in those circles. There was quite some soul in commercial circles, and their increased buying power had even made them the core of the art market. Even pen artists with no affinity to it, if not of the brooding sort, quickly adapted to this market segment, which actually was the segment where Arnheim, though a somewhat special case, had broken through. He had not done so for the money, but in less calculable ways he laid golden eggs there for his concern.

Arnheim. A rare plant that on most places would peter out but the seed of which fell - how Ulrich would love to stress chance - right where conditions existed to become great and spectacular.

Neither was he a snob. He did not want to be part of it, he was above it and looked mildly down on traditional aristocratic grandeur as a great leader of the new bourgeois class on the verge of taking over from tired and degenerated nobility. And his task as king of the new class was much more complicated: the old nobility only had to make minced meat of its opponents and could leave the handling of spiritual weapons to the churches. Now, working with money, you have a weapon that is much more efficient than a knight's bludgeon, but it is dangerously spiritual and hence requires continuous concentrated devotion, or else in some moment of neglect the stock exchange swallows it.

Arnheim saw his royal duties as a tradesman as synthesis, power, bourgeois civilization, the symbolic shape of coming democracy, leadership, new state structure, the future in which the ideal does not break under the forces of reality but purifies and confirms itself, in sum a fusion of business and soul by the overarching idea of the king-tradesman, the sense of love, everything is fundamentally one in the unity of culture and human endeavour.

Such was his state of mind when he started to write books. With a lot of soul in them. Soul! a kingly concept. Old- fashioned rulers and generals do not have it. In de financial world he was the first.

The soul had several uses for Arnheim. First, it had some element of a crown prince in a commercial company getting older and rising against his pragmatic father. Second, in as far as the crown prince did not understand totally everything, the soul was a good method to deprive all he did not understand of its value. And, third, it made him relate, as a child of his time, to his public, by endowing him with a kind of female religious rage against the primacy that knowledge, calculation and balancing had acquired by the rise of money.

But though he issued his moral principles as if it were decrees, it did not get fully clear whether, when dealing with the soul, Arnheim thought of it like as real as his stock portfolio.

This had continued until, like every prophet, he ran into slight embarrassment by what started to look like a delay in the landing of his spiritual architecture on earth and he entered a period of mental cleft in which the mind forgets and switches off everything that does fit the concept. Inadvertently he started to take the air at the same place every time.

Once, for instance, he was dictating another book to his secretary posted behind a type writer. "We see the silence ... " That should have continued as (but the phone rang) as "... of the walls when we look at these buildings ...". But his secretary was on cruising speed and had typed already: "... of the soul, when, ...".

When at resumption the secretary had read the last lines the sessions got ended.

The next day the last sentence was erased entirely.

But! What was, compared to these great and deep thoughts the physical love for a woman? No, all roads to spirit leave from the soul but none of them leads back.

Diotima had grabbed him at his undermoral, secret sleeves. Every now and then he looked at her in a decidedly disturbed way. Just the wife of a civil servant! He could marry the daughter of an American magnate or a young lady of high English nobility! This incident of love made him feel like a rich family's boy dropped at school for the first day: now what is this??

At such moments he admired the cool pure rationality of money compared to the ways of love, but that only indicated that the stage had come in which the prisoner does not understand how he has allowed himself to be deprived of his freedom without defending it, with his life, even.

For when Diotima said: "What are world events? Un peu de bruit autour de notre âme ... !" - then he felt the very structure of his life tremble.

87. Moosbrugger dancing.

Moosbrugger, to Ulrich's surprise according to Clarisse a musician ("he just doesn't know music that's all"), sat in his cell in the investigation department. His lawyer's sails had filled again with new hope that the cow would give more milk before breathing its last breath. When Moosbrugger thought about it his face got a bored smile.

Very neat such a cell. You are everything yourself. Everything looks back as from a mirror. The barred window, that solidly locked door, it was all himself. True to life.

For after all, it was all there was, no God, only the papist, the judge and police, and those only walk in the way.

He had everything under control he thought. Just look how in a cell everything is exactly where it should be, how everything goes according to schedule, eating, airing etc.

"Yes but is that a reason to immediately kill someone?" How often had he heard that? Strange question. It would never have occurred to him to ask. But the mere repetition had raised his theoretical interest.

He was thinking. Pleasurably. Not that thinking in which everything collided all the time. He was in a good period: one single thought, then the next one, and so forth. Not that waddling, like a toddler, no, no, like a dancing girl. A beautiful swell. Accordions, light in the night, daffodils. Kill, a little drop of Moosbruggerblood in the world. Look, if those girls were dancing so nicely in a row, they would not make him so angry. He danced with them.

And nobody saw it.

88. Beware connecting spirit to big things.

For nothing is as dangerous as that. What happens when, totally exhausted, you arrive at a mountain top and you look around? When you have your own child in your arms for the very first time? Probable an awful lot, but where? Probably everywhere but what?

At such a moment you do not know what to say. The mind does not like that, but how could you know at such a moment, it got locked and tied somewhere outside. By whom? Anyway, it is only afterwards that the mind comes back to sweep the floor and put everything back on its place. Then it's time to look at our watch and know again what is the hour and things like that. When the phone rings we again know what to do.

Here you see the law of the conservation of spiritual matter at work. To go to the extreme cases at once: the highest instances of the human spirit, peace, virtue, humanity, well just visit one of those shops where they sell those sport competition prices that are battled for with that typical frantic ardour. The shiny silver stature of the boxer on a tiny bloc of gold inlaid marble, or so it seems. But you buy it cheaper than a cigarette lighter.

This is an instance of the natural order of the mind, a mathematical function: the higher the spiritual significance of what we deal with, the cheaper and emptier the words we use. In the reverse limit: if you want to see the mind in crushing action, go to the tower of Pisa when they discuss how these big stones they drop from the top develop their speed underway. That falling downward they pass every successive ring of pillars faster, but exactly how? Hear them decide to pay a boy to carry up some more stones and then wait there for orders. Hear passers by, on their way to church, joking how you can make a fool of yourself wasting time and money as well.

The first, the spirit's high end has other fascinating features. Just witness the pumping of spirit from one big thing into another that is judged to need some more of it. An academic chair for sport, a music conservatory for popular music. And novel questions of high spiritual value: who took the potato to Europe?

And to shine like a star in contemporary Europe one should be a synthesis of your own and your potato-significance and sing it out as a pop artist.

And I do not have to tell you whom we are talking about.

89. One has to go with one's time.

But now I'm going to mix a pinch of Ulrich in his character.

Arnheim's hotel. After some morning business skirmishes things were done. He lit a cigar and thought of the previous evening. After failing to achieve the breakthrough with the help of the greatest of the mind, Diotima had organized a special evening with somewhat younger spiritual talents. Arnheim had suggested some young foreigners as well. Scare had been in Diotima's eyes, Arnheim remembered with a smile. Well, what this generation had stuffed its brains with had surprised Arnheim as well, he had to concede. Now we turned out to start calling for the control of sensuality and spiritual synthesis, others already got fed up with that and advocated the filtering of all intellectual pollution from the juices of life, all passionately so, of course. New keywords got tossed: "intellectual temperament", the "fast style of thinking jumping on the chest of the world", "the sharp-edged brains of cosmic people". One thing had been beyond doubt: everything had to start from scratch, and altogether differently.

Appalled by the thought of having to leave without conclusion, after ample deliberation it was: our times were full of expectation, impatient, wild and wretched, but the messiah on whom all hopes were focused and whom was waited for, was not yet in sight.

This brought Arnheim in silent private conclave with himself for a moment.

All night there had been a little circle around him. Every time when some who felt short of attention left, but others had taken their place. He had remained the centre of it due to his knowledge of everything that occupied them.

He lit a match for an unusual second cigar but had to postpone suction due to a smile he got while remembering how one moment yesterday night that little general came to him. Arnheim knew all about generals. He met with them regularly. Stumm: "Do you understand why these new people talk, without any expertise, about 'blood generals' all the time? I very well understand those older gentlemen who normally are here, even though neither they have a sense of the military. For instance that older gentleman, the one with the belly who always comes, a famous poet our hostess told me. He deals only with the very biggest of things. That makes sense to me. We call such a man a strategist. Look, a sergeant of course cares for his people but in the calculations of a strategist a thousand is the smallest unit, and he needs to tell us how many of those units will survive under the different strategic options. What is the logic of calling such a man a 'blood general' in one case and a champion of eternal truth in another?".

Arnheim knew that poet but had said nothing. It did not matter anyway, Arnheim knew some more of those old heroes of human spirit.

It felt odd, yes, dismal to Arnheim to hear his youthful admirers ruthlessly scorn that past of which he formed a part. What did they want? They disagreed about everything except their disgust of objectivity, of intellectual responsibility, of the balanced person.

He could not suppress some amusement by yesterday evening's fate of some of his generation. And Stumm's fat poet indeed phrased ridiculously heavy, as the base copper in an orchestra, that's why he was seen as a poet, so why not as a general, a poet like that lends dignity to his life by dealing with death like a factory butcher.

Arnheim supported some of those. Why? If those heraldic heroes could not sustain themselves in their blown-up state they should be relocated in a park of endangered animals. He decided to take them off the list.

So his second cigar even saved him some money.

90. Abdication of idiocracy.

These heraldic men Arnheim just had erased opposed against the commodity market of spirits: pure poetry preaching greatness to their flock in deceased language. It had turned them into heroes, though a bit later they often got abjured again. Arnheim, who felt safely insured, did consider to join the game, for you never know.

But how? Everybody worked in some newly invented profession nowadays, truck driver, radio operator, pilot, you name it, and in leisure time one engaged in newly invented amusement: cinema, cars, motorcycles, sport. And everybody forged a new philosophy of life out of those new activities. The swarm of those millions of brittle and short lived ideas would make it hard for Arnheim to reach the chaotic, bubbling, pressure building inside of all those people, that they knew nothing about.

Had he been able to look ahead some years, he could have seen how after two thousand years of Christianity and a war with 37 million deaths the girls would publicly undress as if they were just peeling a banana, to mention only the least that would have surprised him. The point is not that it happens and how long it lasts, but the ease with which the couturier, the fashion editor and chance achieve this while the investment involved in doing this the official way, using philosophers, painters, poets and all that, would be insurmountable.

Though Arnheim could not think of such things in 1913, the abdication of ideocracy, of the human central nervous system, the displacement of spirit to the periphery, was in his head.

To be honest, of course life refurbishes man always from the outside to the inside. The foundations are, in such matters, the final touch. This, for instance explains why the Dutch still believe they are the descendants of Tacitus' Batavians. Thoughts are the end products of the vicissitudes of the limbs, muscles, glands, eyes, ears and the chimeric impressions the the skin-sack. Previous centuries overvalued rationality, shrewdness, intelligence, conviction, character and such things. That is the department of statistics, not the management.

Suddenly Arnheim felt he had it (but this could have been caused by his state of being in love): the increased sales in the sector of ideas and experiences reflected an increased efficiency of production, caused by refraining from time consuming mental digestion ... and this tremendous and tremendously growing mass of ideas twists and bubbles, thus causing the now emptied inside of the human being like a glow-tube to radiate, producing all those colours. Rational brains would be incapable of such a thing. And the individual is no longer master over it, it goes way too fast, nobody has time to ask what it all is.

Only ... does not this just deal with adolescent dreams of a glorious life or that speech we give in proud self-confidence to that huge mass, the lasts words of which, echoing in us when we wake up, make us drop out of bed of laughter?

At once he felt better: it could not be true.

91. Speculation in ideas à la baisse and à la hausse.

You can't just always keep looking around skeptically with a glass in your hand. To have a break every now and then Tuzzi had the inclination - that by the way he distrusted and restrained - to say something to Ulrich.

That distrust was obviously a good thing to have for when you regularly find yourself in a ridiculous company you have to mind not, out of sheer boredom, sooner or later to go fishing for some understanding and appreciation of your judgment.

That the leak finally broke at Ulrich's side was partly because he often looked bored as well, partly because he seemed not to particularly like Arnheim either, partly, finally, for reasons Tuzzi could not fathom, which gave him reasons for prudence.

He opened by showing off some knowledge of historical detail, so Ulrich would know he could not be fooled with, but right from the start it was spiced with gentlemen's jokes about the spiritual fervour of neighbouring partygoers: "Without responsible official leadership these lads already had killed Christianity".

Ulrich readily agreed: "Religious government officials are right not to allow tampering with the rules and regulations, indeed we generally underestimate the value our lower instincts for they are the driving force of history. Higher urges are too windy, inconsistent and unreliable".

The eyes of the Sektionschef, in mocking overview of the room over a cigarette, turned to Ulrich for a short distrusting glance. "My wife does well to be careful with your cooperation, you tend, if I may say so, to speculation in ideas à la baisse"

"Well said!", Ulrich was serious, "but my market offers are always late, for history itself is always ahead of me. A la baisse with cunning and violence, à la hausse like your wife and Arnheim are doing. So I am always too late for an offer that would earn me some money, and it would be a booster for me to learn some of your secrets as professional baissier".

Tuzzi pulled his cigarette pack to draw another one. "Why would I not think like my wife?" That was meant to block a personal turn in the conversation, but even before he finished, an unspoken swearword tossed through his mind, for he realized it would have the reverse effect.

"The masses acquire a shape by pure chance and that stabilizes for a while", Ulrich said.

"That's too high for me".

Ulrich enjoyed Tuzzi's taciturnity in opposition to his own flux de bouche, not in the least since you familiarize yourself with such a person like you do with an animal, not the worst way at all!

So they stood quite some time together in agreeable silence.

"Well" Ulrich finally said, "I should of course not have started to teach you about diplomacy, but I thought, you might repair some errors in my view. So my claim is that a reliable social order rests on mendacity, cowardice and cannibalism, in short, the lower urges of man, in terms you just taught me: idealism à la baisse".

"Too romantic. Diplomacy isn't intrigue, though many think so, at least nowadays it is no longer so. Our diplomatic conscience demands optimism, and we prevent cannibalism because we believe in something higher and ..."

"What do you believe in?"

"Do you expect I can tell you in a two words like a child can? One has to know the currents of thought in one's own time and the more of those you have the more work it of course requires"

"Of course? But then you agree with me! The sudden and erratic rise and demise of eternal truths causes you more work that the lower urges!". Ulrich barely succeeded to keep assuming the pose of two reserved gentlemen in undercooled conversation.

That prompted another inquisitive gaze but this time Tuzzi's entire body followed his eyes. He was fed up and scanned for a stopper. "You see, philosophizing should be subjected to a strict system of permits".

Ulrich took his time to ponder what would be the best retaliation. Tuzzi, rolling a cigarette, waited for it.

"Yes", Ulrich finally opted, "In this matter the churches, socialism and you have a point".

Not bad. Tuzzi thought best just to wait for Ulrich to continue the oration, and already got irritated in anticipation.

But Ulrich stayed silent. Brilliant! But a bit lucky, since it was because of the pleasure with which he looked at this man who was not afraid to be old fashioned and be known for it. He lapsed into thoughts about how Tuzzi distrusted Arnheim, abhorred Arnheim's influence on his wife, but had no clue whatsoever about her second spring of love.

That is why it escaped him that Tuzzi sensed his benevolence and like a cowboy spit from between his teeth out of constrained irritation, even stepped back a bit, then returned to mask his emotions by asking: "Did you ever ask yourself what this Arnheim is doing here?"

Now it was Ulrich's time to panic and search, putting aside his acute embarrassment, for a wrong answer that could be one for Tuzzi to believe to be honest. In vain. He resorted to a question: "Do you really think he has a special reason? Then purely commercial I presume?"

"What else?", Tuzzi said.

"No you're right, what could it be", Ulrich conceded, relieved, "though for a second I thought of his literary ambitions".

"Then explain me those ambitions".

"Have you noticed", Ulrich started - which made Tuzzi already lose his interest - "how many people nowadays mumble in themselves while on the street? This an overflow of impressions. It drains the surplus. That's why they write too".

"I read Arnheim, for some see him rise, but he can't possibly think he is boosting a political career that way".

"Yes, a rich man venerating simplicity, it is a bit ... look, poor people write about the rich in admiration, or they create phantasy wealth to have something similar ... "

"Have you ever written something?" Tuzzi asked, hoping for the leverage an affirmative answer would give him.

"No for that disastrous fate I have been saved, even though I am unhappy enough for it, I will prevent it with all means, even if I have to kill myself".

Thus the stream of the gentlemen's conversation petered out and a rock had surfaced. Tuzzi sensed it and came to the rescue. "It seems to me like when I am saying civil servants start to write only after they retired. But Arnheim?"

After this elegant rescue by Tuzzi they continued a little bit. Tuzzi managed to push Ulrich slightly out of balance again by calling Arnheim "essentially a pessimist", but failed to draw cash by it, the gentleman parted, both with the memory of a stern conversation.

92. Some maxims of the rich.

Another man might have become suspicious and unsure by the attention and admiration that Arnheim got snowed under with. But Arnheim held firm control over it for he stood above it. From such a position the quality of the admiration you harvest is irrelevant. The admiration itself is what matters. You boost it everywhere you feel the ground is fertile and you avoid ground that isn't.

You simply have ideas and challenges different from those of the average person when you, as a rich man with vision, are endowed with the routines to control events with your money, spent with the perspective of seeing it flow back in a cascade of future installments.

A poor man does not have the faintest idea that one can buy thoughts, knowledge, loyalty, talent, prudence. It's all there, eagerly waiting for a man with money and vision. Sure, the man with the money and the vision cannot afford any lapse of attention: a small error and a large chunk of wealth is gone. But even lavish parties can pay off, if you know whom to invite, and focus on the long run. Who knows such things? Arnheim's admirers did not even realize what exactly was the admirable in him, nor should they, for one does not allow strangers a glimpse in your kitchen, that would make things only harder.

How do you deal with whomever wants money from you? The hopeful usually has no clue. He wants to do something, sees a man with a lot of money who might be ready to cede some to ... and oddly enough the Great Men of the "Geist" are no exception in this, for they never think of such things and only see that your wallet gets thin while good, not to say eternal ideas lie, unsold, on the shelve.

So how are they dealt with? Most of them will never realize that somewhere, if only in a niche, whith a limited probability, they fitted in the strategy of the concern, and that somewhere in the line somebody's nodding did the job.

As everything in nature, money's endeavour is to survive and procreate. To just give some money to a nice person would be totally inconsistent with its nature. Was there such a merely praiseworthy goal, Arnheim would always say money should be spent. But not his.

Thus Arnheim had earned his reputation of a man who participated with power and creativity in the cultural development of his times.

And why are you admired and loved? Isn't that an impenetrable mystery, as round and tender as an egg? Are your side-whiskers a more legitimate target than you car? In this period, a year before the First World War, the man shaved. But Arnheim sported a moustache and a tiny chin-beard. Those little hears, oddly attached to his head yet being part of him reminded him - he did not exactly know why - when he got a bit overexcited during a speech for a fervent public, in an agreeable way of his money.

93. Civil understanding, even if underway to body culture, is hard to grasp.

Already for quite some time the general sat on one of the chairs surrounding Diotima's spiritual gymnastic floor. With Ulrich, his "protector", as he liked to call him lately. His bright blue dress always crept up on his fat little belly in folds when he was seated and started to look like thinking folds as on someone's forehead.

Right before these two, slightly above them, the question was discussed whether Beaupré's tennis was or was not a genius' work and Braddock's scientific. One started wondering about the mutual balance of matches. Nobody knew "Let's ask Arnheim". The group dissolved.

"If", Stumm said, "such a tennis player is a genius then why is a general a barbarian?"

94. Diotima's nights.

Diotima filled with pride when she compared her social glory with her limited middle class youth, but she could even reach a bit higher, she thought, even past World Austria. The highest of course would be marrying Arnheim, throwing herself like a girl into the arms of her father. Love and ambition continued to develop as two separate lines.

She should have opened herself to her husband. But what was there to say? Nothing had happened and he was not the man to address when the subject was the embrace of souls. Strange. Yes. Nothing to say. There was not even any prospect in the physical sphere. This she even would deem better imaginable in the direction of her broad shouldered muscled nephew, whom she thought of as younger than herself, certainly in mental respect.

Moreover, on the road to Prussia, Austria was in the way. The normal Austrian reservations against Prussia were based on the time honoured expedient to seek, for every irritation about the self, an external cause and Diotima had not shunned the use of this popular palliative, so the thought of burning Austria behind her left her unsure and inspired her to call the whole thing, rather than love: passion.

In her sleepless nights the Prussian blue of the sky was fighting with Mozart, Haydn, Beeethoven, Prince Eugen and the black-yellow of her fatherland. Her soul found itself hopeless, in an endless blossoming landscape inside her tall beautiful body.

She suffered of her husband's hard-headed insensibility but she could not hate him for it for it formed an integral part of his sense of duty and his amazing diplomatic career. How could she destroy the life of this man? No, adultery was the best option!

But then again such a stealth mode of operation has this whorish flavour in contrast to which the Last Meeting, words of goodbye square in the throat, a renaissance love with the dagger in the heart, sin and overcoming the guilt, lust punished with suffering, compete not without merit.

Meanwhile, next to her in bed, Tuzzi had gone over things one more time, had concluded that in the coming eight hours of sleep nothing could get out of hand in Europe, and breathed regularly. Innocence itself.

Abstinence! Diotima thought. Goodbye to Arnheim!

And then continuing in this double bed? Vanished was Tuzzi's innocence, and there he was again that snake with that sweet little rabbit in his body. But no tears, no grabbing of his throat, no: Ulrich, who would, if he could, abolish reality - might he not mean something quite sensible with that? And Ulrich again, who clearly thought she overestimated Arnheim.

Well, what could one do really? Nothing! Another sense in which you have no say about anything. You can only wait and see what happens to you.

That thought drew a curve before her behind which the end point disappeared. She would sleep a bit after drinking some sugar water she always had next to her, but never thought of taking during her nervous mental slaloms.

95 The grandauthor, view from the back.

Since the celebrity guests had convinced themselves that the seriousness of the Great Initiative did not require a great strain from their side, and had become familiar with each other in a regular sequence of agreeable circumstances, one by one they had decided to leave their masks at home and started to behave like human beings, as a result of which Diotima chiefly started to feel haunted by noise and spirit. And relief, namely when at the end of the evening the last drunkard had waddled on the front side street pavement.

She even started to sense some disappointment about Arnheim's lively intercourse with these buffoons of the great Austrian mind even though, with growing amazement, she kept realizing these were the men the books of whom filled the bookshelves in her boudoir, and were found prominently displayed in quality book shops.

She should have realized Arnheim was no sovereign of the mind but a grandauthor. The grandauthor is on the verge to replace the sovereign of the mind, in the same way as the great merchant is on the verge to replace nobility. The grandauthor connects the mind with great things but in the modern way: he has a car, as long as this still is something remarkable, after which he will buy his own airplane. He travels, is received by ministers. He convinces the managers of public opinion of his power as chargé d'affaires of the spirit of nations.

His book will not be the book of the year for he is the chairman of the jury. He writes prefaces, is the one who does the speeches on all important birthdays, leads the opinion in important matters and is called in at every meeting meant to show how far you got. On behalf of the moderate future-minded he reassuringly addresses the backward.

History gave birth to the greatindustrial mind. And meanwhile we have overproduction and stagnating markets. The problem is that consumers experience excess private stocks of spirit and themselves regularly consider to advertise and get rid of some. Now this is the development that called for a grandauthor. To grab the post you should see it as one of the first, but understandably you will not be alone. In the converging horde things get decided: grand, grander, grandest. And you have to be the grandest. Who will remember number two's name? Moreover social efficiency requires one-head leadership.

How to reach that enviable top? The biggest mistake would be to add more spirit yourself. There is far too much already! Your first attention should be: fighting unwanted spirit. High places will be grateful so it is profitable business even in money terms. And a keen sense for this is likely when a would-be grandauthor happens himself to be a top merchant of international stature. Moreover, this consolidates a large part of the transaction inside one business house.