| East Africa Home |

| Kiswahili Home |

Crtd 04-11-27 Lastedit 14-11-18

Kiswahili, no plobrem

Kiswahili today and in history

Kiswahili is not

an original native African language. It originated as a kind of "Esperanto", a

simplified intertribal Bantu language, used for trade and diplomacy between

Bantu tribes among each other and with the Arabs at the coast of Tanzania and

Kenya. The most profitable selling item of the "Kiswahili"-people slaves. Their

business consisted of raiding the East African inland, chaining entire village

populations and selling all who survived the journey on foot to the coast.

Nobody in Africa seems to remember that it was the ethnic Africans who made

(captured) the slaves. Foreigners only bought them and consequently those

foreigners, now sometimes held liable by Africans to pay damages for

slavery, actually should receive them, because first, ethnic Africans

sold them slaves, then those ethnic Africans started to teach the buyers that

slavery was immoral, after which the slaves have been freed. But the money has

never been returned.

As a result of the Arab presence at the East African coast, Kiswahili has had a heavy influx of Arab words. Nowadays, one

would expect English influences. They are there (see below), but much more

limited than the Arab influence. Though "bar" is baa and "server" is

seva, website is kuraza pembuzi tovuti, "processor" is

kichakato, and

"hard drive" is kisukumo msingi. Kiswahili speakers are not even shy to have their own word for

"iceberg": kisiwa barafu,

though nowhere there ground temperatures below 17o

C can be felt.

Kiswahili is spoken in Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and its bordering regions,

especially East Congo. That is about the range of the African slave (and ivory)

trade.

The author on the Page One of his Kiswahili book (left Supa, right Haipa)

Grammar: astonishing to westerners

Though having a lot of foreign words, Kiswahili

has a Bantu grammar. This grammar is amazing to any speaker of an Indo Germanic

or Slavic language, whose first question about a word is: "is it male or female

(or neutre)?". French does not even have neutral words (only le and

la). German and Dutch allow for neutral (dass, het respectively), but

sex remains the foundation of grammatical distinctions. Even in English sex is

deep down, for instance where we have to decide how to say: "the committee has

not yet advised because he/she/it needs more information".

Bantu (Watu in Kiswahili simply means "people") take no grammatical interest in

sex. Of course, you have men (wanamume) and women (wanamke), but

there is no difference in their grammatical treatment. Kiswahili speakers have

other basic grammatical interests: you can talk about

people (plural for people everything is is wa: watu wetu wale wakubwa wamekuja - "those big people of ours have come")

other creatures that move around seemingly on their own initiative (animals, insects, fishes)

plants ("orange tree" is mchungwa, pl. michungwa)

edible parts of plants ("orange" is chungwa, "oranges" is machungwa)

dead things and tools we use in life bulk matter (earth, maize porridge) and abstract concepts (badness, old age)

words referring to time and place, that is where and when something is (or was, will be) to be found

It has advantages: when you hear for instance, the little boys of the neighbors say ni kidogo, "it is small", you can be sure it is not about each others penises because none of the sixteen words for penis are in the KI/VI - class.

This division in 7 classes is good enough to learn Kiswahili, though there are a lot of exceptions and even hybrid classes.

For verbs, you have a number of postfixes:

funga (shut), fungwa (be shut), fungika (become shut),

fungia (shut for), fungisha (cause to shut), and so on.

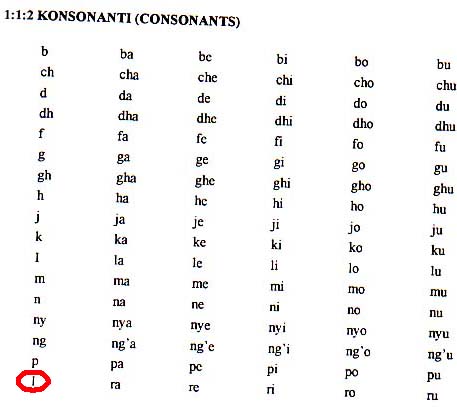

Pronunciation.

Kiswahili is easy to pronounce for westerners, especially when

you speak Italian. The syllable pattern is (single) consonant-vowel-(single)

consonant-vowel. The word ending is always a vowel, the stress is always on the

vowel before the last

one. Hence my name "Bert" is difficult: a

double consonant ending. The easiest and most common Kiswahili solution is

to say Btti. Kiswahili speakers who go for pleasing me with a final consonant

torture their tongues in order to end up with Brrelt. If any Dutchman

called Henk

does not want to be called Heki, this requires his daily attention. Kiswahili girls

called Jane are always called Jani and used to that. Peter will be

Pta. Some English words used by Kiswahili speakers: bar ba

(two separate a's with the stress on the first one). Shirt shti. Spare

spa. Bus: bsi. This prohibition of stress on the last vowel is

an absolute dogma in Kiswahili. Even when that last vowel has the stress of the

speakers intention, he will pronounce it unstressed. For instance

je (how) in alifanyeje (how did he do it) leaves the honour

of stress to ye which has little meaning apart from announcing that an

item in the ("after ye")-class of endings is going to follow.

The consonant-vowel-consonant-vowel preference in Kiswahili does not only

imply that often vowels are added. Sometimes they are skipped for

the same reason. For instance, to Kiswahili speakers, m is a vowel in many

cases, so they do not need an additional vowel o as the Portuguese in

"Mozambique": Msumbiji.

A more confusing difficulty, however, is the distinction between "l" and "r". When Kiswahili people speak English, I often hear "praying" when they want to say ""playing", and "playing" when they want to say "praying". The amazing thing is that they have no plobrem understanding the westerner's English pronunciation of "l" and "r". But I experienced absurd conversations like these:

Jeremia: at the next junction, we go light .

I: What is right in Kiswahili, Jeremia?

Jeremia: Kuria

I: And left?

Jeremia: Kushoto.

I: OK, so I can easily remember it: kuria has the "r" of "right"...

Jeremia: Yes, the r of light.

The dictionary turns out to give for "right": kulia with the l of "left".

Different Bantu languages generate "r" resp. "l" impressions in western ears at

different praces. There is no genelar lure.

Even Kiswahili text books find it hard to maintain "l" and "r" on there own praces

in the arfabet.

Vocabulary

Tu is not "you", as in Roman languages, but

"we"

M is not

"me" but

"you"(plural), and also "him", and thirdly, it can denote present

perfect, culminating in expressions like (Mmempa yeye You have given

him − M-me-m-pa

You-have-him-give)

Nane looks like

"nine" in many indo

European languages but it is

"eight"

Sita is

"six", and

should not be confused with Tisa

Tisa looks like

"thousand" but it is

"nine"

Mbili looks like

"mille" or

"million" thus

could thought to be

"thousand" or

"million", but it is

"two".

Elfu is not

"eleven" but

"thousand".

Si,

"yes" in Roman languages, means

"is not", negation

Ni, negation in all Indo-Germanic languages, is

"yes", affirming, positive.

Dada does not mean

"father" but

"sister"

Amekaa mbele fortunately does not mean

"American car", it means:

"the one sitting in front"

Hawana unfortunately has nothing to to with my cherished Cuban cigars,

that are very hard to get here. Hawana Havana means:

"they have no Havana's".

Kiswahili has arisen out of the necessity for

Bantu tribes to communicate in the East African trade boosted by the Arabs. It contains a host of Arab words. Arabs had a sophisticated

money economy (check is

an Arab invention and an Arab word!). It is all the more surprising that in Kiswahili, "bank"

is benk,

"change" is chenji. For "money" itself there are three words,

fedha

(Arab), hela (Hindi, Indians are the backbone of the East African

economy) and pesa, the origin of which, according to the authoritative

Johnson dictionary, is the Hindi "![]() ". That makes us end up without any traditional Bantu word for money.

". That makes us end up without any traditional Bantu word for money.

Quite thoughtfully Tumo baa ("We are in the bar"), has been chosen such as to be understandable even if spoken after quite some beers through a bad phone line. Why Kiswahili waited for the English to provide a word for "blue", (buluu), is an intriguing question. Kiswahili people tend not to give names to colors, but to say "the colour of...." (leaf, dry leaf, coffee, ash, turmeric)

The Germans and Dutch will be pleased to note that a "small mountain" (mlima) is kilima, a "small child" (mtoto) is kitoto etc. (so the German and Dutch klein, and not the English "small" or French petit). Mengi is many (Dutch: menige), ingine can mean "few" (German einige, Dutch: enige). "To enter" is ingia, in Dutch: ingaan. "Egg" is yai (Dutch ei, pronounces ai in German, including some Dutch dialects). All purely accidental, or would it have a background in instinctive primitive sound language developed in the time our ancestors were still laying eggs? "Ai!!!" Ultimate satisfaction for Germans: "School" is Schule in Kiswahili, but this really is a German loan-word.

To my utter astonishment Kiswahili has a word for a unit of seven days, hence "week". Why seven? How on earth would non Mesopotamic peoples have such a 7 days unit? It it is not based on any astronomical cycle whatsoever hence completely arbitrary. Answer: from de Muslims: "day 1" is Saturday, "day 7" is Friday. This leaves us in limbo concerning the true traditional Bantu handling of days, months and years.

Dictionary problems

Words, both nouns and verbs, get prefixes. The stem ti

means chair, but one always hears or sees it as kiti (sg.) or viti

(pl.). Pend is "want", but you always see or hear it like ninapenda, "I

want", sipendi, "I do not want" (i is a postfix and there are many types).

Hence one should know the word stem to find a word in an alphabetical

dictionary, typically something you do not know if you need to search for its

meaning.

I do not know for sure, but I have little doubt that the first Kiswahili writing

was in Arab letters. East Africa was at the fringe of Arab culture for at least

nine centuries before it was "discovered" (as the retarded Christians call

the event of their own first arrival after everyone else). No doubt reading

Kiswahili in Arab letters is much more appropriate, not only since you read in the opposite

direction (somebody told me I make a mistake here, but his argument was to

complicated for me).

Meanwhile I found (Encyclopaedia Britannica): The oldest preserved Kiswahili literature, which dates from the early 18th century, is written in the Arabic script.

Being forced on the barbaric Western alphabetization of Kiswahili, I took some Kiswahili dictionaries from the internet and merged them in a database. So, I now can type kiti, or ninapenda to select some 20 entries in which that grammatical form of the word is used, or type pend, to see if the selected records tell me whether or not it is a verb-stem.

My Standard Kiswahili - English Dictionary (founded on Madan's Kiswahili - English Dictionary) by the Late Frederick Johnson, with a foreword of the Bishop Thomas of Zanzibar, 1939, contains over 25 000 entries. Overviewing my downloaded internet digital dictionaries and making a reasonable correction for (Kiswahili) doubles, I estimate I have over 50 000 Kiswahili words in my computer, curiously enough, the Late Frederick Johnson has not (yet) been fully absorbed there (no scanner and text recognition software? Can I earn a little money from my African hut here in Mwanza?). It must be said that Kiswahili speakers, if they would overcome their abhorrence of counting, may come to a number lower than 50 000. For instance, there is a pack of card's number of words containing -fung- (close), every one of which makes a word related to opening or closing in a systematic way, an unzipper, so to say, that applies generally in the language, so e.g. to a stem like -pig- ("beat"). Since a lot of western vocabulary is simply absent or only wordable in word combinations, in its own fields Kiswahili must definitely rank top or close to top in richness, with shades of meaning that would take westerners ages to grasp.

Photo: One year after Kiswahili Page 1: author just finished his Kiswahili book. For personal Kiswahili details, click on picture.

Photo:

One year after Kiswahili Page 1: Supa

(Haipa long

dead).

OK. Swahiri no plobrem? Click : Let's get serious about this "l" and "r" issue.