| Greetings Home |

| Previous Greeting |

| Next Greeting |

| More About Kiswahili |

Crtd 05-09-20 Lastedit 19-02-09

Personal Kiswahili vicissitudes

Actually I am crazy now. My mind is waving like a flag that urgently has to be lowered because of heavy storm conditions. Last week I decided I was fed up with reading my Kiswahili text book and went for doing two chapters a day. I made it. I FINISHED THE BLOODY BOOK! But really, my present state of mind matches in discomfort with the one in which I felt forced to stay home because I needed to learn the bloody language people speak outside. I try to ease the storm with cold Kilimanjaro beer.

But (lakini)...I SPEAK SWAHILI NINASEMA KISWAHILI AND DON'T YOU LAUGH

ABOUT IT! That is, I can write any letter on any subject in Kiswahili. It will

contain a host of errors, but Kiswahili people will understand what I mean. This

writing of Kiswahili lasts roughly one page in two days of hard working. The speaking

on a subject hence takes more time than any listener could endure, but the words and

sentence formation is there, so, the job

now is activating and smoothening the bloody shit.

This means action in town without translators. I want to build a small

catamaran, the two boats of which independently usable rowing boats or canoes.

For this I will not invoke any help. I will simply go to town and buy and order

what I need. I will sit for hours at the dhow yard, chatting about all that

money they would have would they finish the damned wreck. Etc.

My native language is Gronings. It is belonging to Platduuts (stress a), the dialect group of the Northern German and Dutch lowland planes called Lower Saxony (plat means "flat" and that is what my country is perfectly indeed, duuts means German, the main cities are Hamburg, Bremen, Oldenburg, Emden and Groningen). Another meaning of Plattdeutsch in German is: "clear, not liable to misunderstandings" (example). The first foreign foreign language I learned was Dutch. First at primary school, because Groningen unfortunately is a Dutch colony. At the age of 9 I moved to Utrecht, the centre of The Netherlands, and thus had the opportunity to improve my control of this defective language, a degenerate dialect of German, and useless too, since the number of speakers, apart form South Africa is 16 million worldwide (far less than Platduuts). Then followed, basically on high school, English, German, French, Greek, Latin. Later I learned Russian. So Kiswahili is my eighth foreign language. Now, with learning the eighth foreign language it is just like with driving your eighth car: you do have more time to watch the landscape while you go. This is what this page is about.

My serious progress in Russian was at the relatively late age of 43-46. Later I have lived in France and noticed that, groping for French words I did not know, the Russian came up (which is OK in a few cases like "bistro" and "raboter"). Now, in Kiswahili, this Russian really became a plague. It seems that brains over 40 are unable to create new language departments. Learning Kiswahili drastically activated my Russian. Against my will! I was shocked by my detailed and thorough knowledge of Russian. It was as if I walked in Moscow every day. This must really be interesting fodder for neurologists.

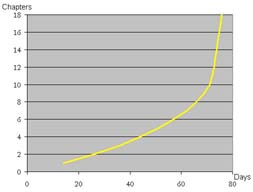

Another amazing fact is the increase in speed of comprehension while studying the Kiswahili book. The book has 18 Chapters of similar size and structure. The first few took me more almost two weeks each. The last one took me half a day.

I started the book as a part time study and ended full time, but the graph is generously corrected for this, and thus, I think purely reflects the increase of the capacity speed of absorption of book pages by the brain: the "amount" the brain had to learn in the first four chapters is simply not reflected in the amount of pages in those chapters. There were some basic transformations in sentence-processing to be acquired, say a new, Kiswahili-specific, basic language processing capacity (brain-"software"). After that was in order the brain-train started to gain speed.

What was that basic Kiswahili language processing capacity? I know, and it is easily

explained what it is. Not to really acquire it.

To "see", "come upon"is kukuta (where the first ku means "to",

then kut is the verb stem and a is the default verb-end syllable).

Now, "if they would not have met each other" is wasingalikutana.

na indicates reflexivity "each other"

li is past tense marker

ngali turns the past tense marker in a hypothetical ("if it would have

been that...")

wa means "they"

si is negation. But

there is not one negation marker, as "not" in English: every person for instance

(I, you, he etc) has its own negation prefix.

Hence wasingalikutana.

At first sight, it seems awkward to omit spacing. The English

could retaliate to this inhospitability and write "iftheywouldnothavemeteachother".

When, however, at the Yacht Club, I told about my plans to learn Kiswahili, the Tanzanians reassured me: Kiswahili was, they said, very easy.

Not something extremely difficult like English.

Think of a language where verbs tend to be modified to express not only things

like present and past, but also whether something is done or happened to

someone, to whom, or what, where there are eight different classes of whom's and

what's that each have their own prefixes, postfixes and interfixes, whether

something is going on or is completed, whether some is just done or done with

fervor, and much more, then you think of ... Kiswahili (in fact, of the whole

family of Bantu languages).

Then consider again the abandoning of word separation in English:

Iftheywouldnothavemeteachother

Then think of students of English performing the task previously assigned to

authors of text: splitting up in words:

Ifth ey wo uld no thave meteacho ther

I fthe ywoul dno tha veme teach other

etc.

The poor chap trying to learn Kiswahili has no clue that wasingalikutana should

be split up wa-si-ngali-kut-an-a. He may go for wasi-ngali-ku-tan-a, take

the Kiswahili dictionary and find there (really!): wasi ("insurrection"), ugali ("polenta") angali, lingali and kingali

(all meaning "still"). He finds -tana ("separate", verb) hence

- since ku is the Kiswahili infinitive verb marker ("to") - will be

absolutely sure that kutana means "to separate".

All completely wrong and totally irrelevant to the meaning of

wasingalikutana. After fourty days learning

Kiswahili (see graph above) you will be in your full rights to commit suicide.

I avoided that by spreading those first forty days over half a year. Then

suddenly, my brain started cutting Kiswahili words like fresh crispy French

baguettes.

And there was another revolutionary cerebral development. I was suddenly able, in the midst of this fierce Russian-Kiswahili battle, to find the harmonies of jazz standards on piano without the aid of written scores before my nose. The new thing is not that those harmonies are in my mind. As a saxophone player I have been improvising on hundreds of jazz standards for decades, in all keys, so I know them. But on piano I could not easily find the "accompaniment", that is the changes of the harmony through a piece. I needed music paper to read chord symbols, what the Germans call donkey bridges (used by the stupid ones to cross). NO MORE! Its coincidence with sudden cerebral Kiswahili word splitting skills accidental? I doubt it. Learning new words and language sounds is closely related to music. It is my hunch that my brain, in grasping Kiswahili verb structure, somehow activated dormant neurological algorithms also useful for actively gaining control over musical harmonies on an instrument that can produce many tones at the same time.

Do not ask more about this. I have no clue whatsoever. My brain

started swallowing Kiswahili text book chapters faster

and faster. Now the holes were there, it became just a matter of how many

pigeons per hour I managed to press through.

So, I tried to end up as a circus artist processing as many pigeons as I could, gaining

speed all the time under the ruffle of the orchestra's drums.

But there, I had not reckoned with Joan Russel, author of my Kiswahili book. The

thing is that her (or his, there was even a Pope called Joan, but I like to

think of him being her) writing of the book must have gone the same way as my

reading: in the last quarter, she must gradually either have become fed up with it or

have become pressed by the editor to finish the manuscript. This has led to what

I have come to call "gravel pits" in the last quarter of the book (in analogy to the

gravel pits that prudent downhill road builders construct as a refuge for

descending truck drivers who loose control over their vehicle). Gravel pits

are places in the book where my brain, arriving

with high speed, unsuspectedly got smothered up to loose its pace in a

bad headache. Earlier in the book, Joan had been at pains to introduce in her

example dialogues the right dose of new words and word forms for the reader to

grasp their meaning from the part of the sentence he was already made familiar

with previously. Moreover, all words not yet used, and all expressions not yet

known for advanced grammatical reasons were in the list of English translations

next to the dialogue. In the last chapters, dialogues seemed to consist of

unknown words and word forms only, often the words were not on the side list,

not even in the book's index word list, and even some grammatical structures were

not dealt with. I had downloaded from the internet the Kamusi Project English-Kiswahili

Dictionary

The Internet Living Kiswahili Dictionaries and the Internet Living Kiswahili

Dictionary Project databases are intellectual property protected by international copyright law, c 1994-2000, Yale Program in African Languages, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA.

which I had converted to a smoothly searchable database of 60

000 (!) entries. It helped me out of every gravel pit, but not without

coming to complete standstill in Russel's book. At other places near the

end, her practice questions were far too easy and did not relate to what had to

be learned from the chapter, and side lists to dialogues started to contain

known words. I had to scan the grammatical index, word-recognize

it, import it in my database and extend it with a host of failing numbers of pages featuring

grammatical items I wanted to be able quickly to find.

Clearly Joan and I both got sick of it at the end, I felt a solidarity and a

transcendental togetherness. And what the heck, she got me were I had to be!

Thanks Joan.

Some Official Statements Of Apology:

1. I did call the Kiswahili people "inhospitable" as compared to the English in writing, for not separating words like waimeshikwa into wa-i-me-shik-w-a. But in speaking, the Kiswahili people are much more foreigner friendly than the English: every Swaihili "word" (in the Kiswahili meaning of word, so waimeshikwa is one word) has its stress on the syllable preceding the final one. Therefore, unlike the English, in spoken Kiswahili stress is used as a word separator (stress always means: "after the next syllable I will start a new word!"), which is very convenient to the learner. Second: since my writing criticism is on the western (Roman) alphabetization of Kiswahili, made only a hundred years ago after the arrival of westerners, we may wonder - about the no verb separation issue in writing - whodunit (may be a westerner!). Before that, an Arab writing was used by some (which can't be worse so should be better, see my pages on consonant problems in the general issues section). Finally until the present day, Bantu are generally uninterested in the western (and Arab) idea of writing so they cannot be blamed. Sorry folks.

2. I do sincerely wish to apologize to the donkeys for having followed above the primitive habit of humans to associate them with stupidity. I am personally acquainted with many donkeys, and I am perfectly aware that donkeys on average, I do not wish to talk about the individual exceptions, are surprisingly far more intelligent than, for instance, horses and as company far preferable to quite a number of people, among which especially those who think donkeys are stupid (details).

Sitting in a small airplane from Hamburg ready for takeoff, pilot takes mike,

omits standard phrases, only says " 's geht los ".

Passengers, mostly Lower Saxons, applaud.

| Greetings Home |

| Previous Greeting |

| Next Greeting |