Crtd 15-10-00 Lastedit

20-12-13

Relativity Theory

Maybe this was just TOO crazy

After recently finishing the part of Musil's Der Mann Ohne

Eigenschaften that had set out to relate [see

my Musil relation], I

had promised myself to finally acquire understanding of relativity theory, probably

because Musil's protagonist Ulrich's last career disappointment had been

... mathematics! Ulrich's disappointment came a few days before the day where Musil's

book starts: for the first time a horse had had been called "genial" in a newspaper

which had prompted him to abandon his highly promising university math post with

immediate effect. He was 32, very good at it, known in the literature for some

results. No doubt he knew relativity theory: it was new, sensational, and if you

are trained to read it, you do so. Surely if you are Ulrich. But then came the

genial horse. At the start of Musil's book,

Ulrich had lost his very last jealousy and

ambition and, now firmly aware of the ridiculous state of man, from small to

great, and his history, took time off to search back in Vienna for purpose,

albeit with a worryingly blank notebook.

Not me. I would need quite a bit more time to loose my ambitions,

also to learn relativity theory, certainly after reading, in Der Mann,

the opinions of top Austrian Imperial government dignitary Graf Leinsdorf, who

shouted in 1913, when Einstein was engaged in publishing his general version of relativity theory while few yet had understood

the previous very simply first version: "This psychoanalysis and relativity

theory or how you call all that crap, it bubbles up irresponsibly, and does not

care for the larger social consequences! ... we quickly knock something together

and before we even started to look whether it is something viable we are already

engaged with the next, or even missed the whole thing! A piggery!". I can't help

thinking of those cats and dogs of new

Microsoft Windows versions raining on us. And not only that!

His Serene Highness Count Leinsdorf had a point

indeed.

But I had no time for relativity theory: my head, in 1982, was

fully occupied with my dissertation that caused, to my total surprise, a row

among the midget economics professors of Amsterdam University in 1983 and then

got read by nobody, at least nobody serious - probably no reason for the world

to mourn, though it is excellent, original and could have helped the intelligent

mathematical economist to efficiently order his procedures - but again: there

surely was no disaster there to prevent. Anyway, who listens to them?

I am still remembering with pleasure the making that analysis, 25

years old, with a university salary that I totally failed to consume, a 25%

teaching load and no publication pressure to threaten the quality of my work.

... my summer 1982

first reading (it looks I've just started!) of Musil's Der Mann ohne

Eigenschaften (got into it through Wittgenstein's Tractatus

Logico-Philosophicus by Ulrich's contemporary Viennese Ludwig Wittgenstein

who no doubt forms a substantial part of Musil's material for Ulrich's

personality) while writing my dissertation on dynamic logico-mathematical

analysis of economic theories (published as Neoclassical Theory

Structure and Theory Development, Studies in Contemporary Economics, Vol. 4,

Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokyo: Springer Verlag, 1983 ...

In my early academic profession,

relativity theory was the most admired of theories. This surely

was caused by its overturning of a very admired and totally established

general

theory of physics, Newtonian mechanics, replacing it with something looking very

weird to the ordinary eye which nevertheless yields more accurate predictions

and descriptions of physical processes.

In the nineteenth century, the prediction and description problems

of Newtonian mechanics increased with the increase of the number of ways and of

the accuracy by which one learned to measure not only body movements, but especially

electricity and light in the nineteenth century. A proliferation of inperspicuous

and unsatisfactoy special laws and corrections to match theory with measurement

began to cause more and more headaches and frustrations among theoretical

physicists: things became a mess!

Roughly the choices were to 1) let chaos grow, 2) try to find a general error in which mankind was used,

for thousands of years, to measure time, or distance, or both, or, by far the

most absurd option, 3) to concede that our way to measure meters and seconds did

not result in the identical quantities for

every method of measuring physical processes, that is, to concede that

when meters and seconds in a system are measured from another system that

moves, they are meters and seconds of different lengths. This most absurd

third option to straighten the growing mass of measurement "errors" out

(implying they were no errors after all) turned out to win the prize, gain general acceptance and become

the new truth.

First, as so often in such cases, the idea was proposed by a nerd who had found a

living outside the academic world. After all, universities were originally

founded to maintain tradition, and keep doing so up into the wearing of those

ridiculous black guild suits of three centuries ago. We should be happy that this outsider

did so a century ago, since nowadays he would surely not have found people

willing to consider his very strange and difficult solution of the puzzle. There

are so many of those fools aren't there? And we have no more time nowadays to

read other people's thoughts: we have to publish!

Einstein presented a crude relativity

theory for very special cases of systems

moving in space without any acceleration or deceleration, hence even without

gravity forces.

Many physicists, and not the worst, opposed relativity theory.

Despite the extremely restrictive conditions of the first version, these Heroic

Defenders of Academic Tradition quickly lost the battle, due to overwhelming success of relativity in applying to many

cases with far less need for cumbersome special corrections to make things fit.

Relativity theory soon did

better in quite some applications than Newtonian mechanics in describing lots of processes involving,

roughly, speeds of more than 100,000 km/sec, that is more than about a third of

the speed of light. Those are areas way off the public domain, only known to

specialist physics experimenters. In generally known common lower speed processes

relativity should be better than Newton as well, but

measurement had not yet reached the required precision to measure the

difference, and once it finally started to do so, these differences were, usually, only of

interest to experts.

My good luck was to find an emeritus professor of physics in the

12footdinghy

racing competitions, so I could get some help collecting the literature and

solving problems. But those came earlier than I thought and were more serious:

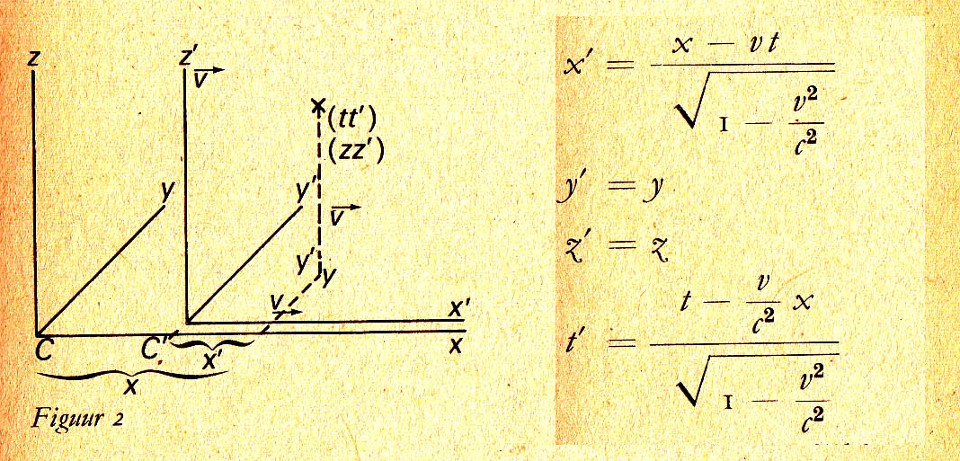

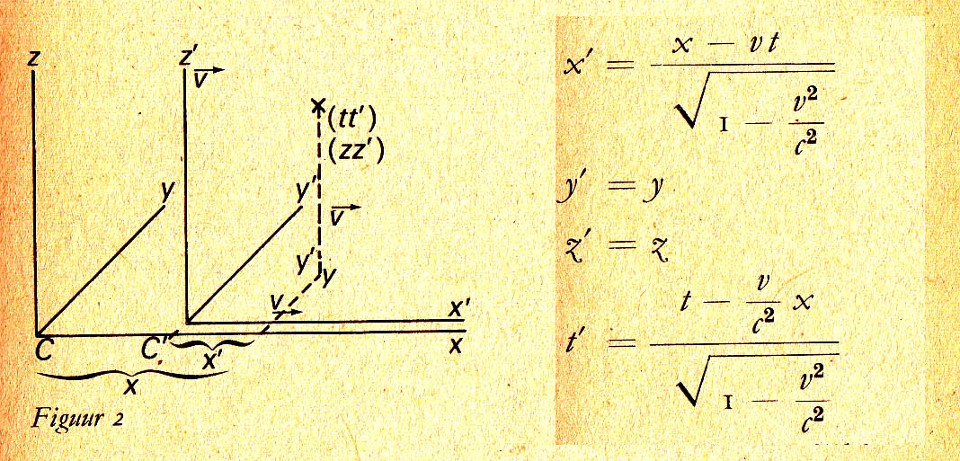

in a popular exposition, Einstein does the fundamental Lorentz transformation.

The most simple case even. The math is easy, but I got

no clue whatsoever what we were talking about: space and time shift relative

to the objects moving around but the speed of light is assumed constant.

But what is "constant"? Speed means: abridging some amount of space in some

amount of time. Now it does so while both keep changing. That light must be

smart indeed to keep track of all those movements, far smarter than myself to

say the least! I might need a real teacher ...

...

Lorentz-transformation. This was most of what Einstein needed for his first

(1905) revolution ...

The Utrecht University web site turned out a total disaster. Paddling around a

home page that was aggressively trying to divert my attention to a "virtual sleeping coach" and an

"anti-teasing program", I found, with great strain, a course

name "mechanics", but could not even find the address of the offices of the

physics staff, let alone the books, lecture rooms and times of service.

Nothing left but taking my car and heading for the "Uithof".

At the entrance of the large university campus a signpost encourages me to

navigate on the name of the street I wish to reach. A bit discouraging for I had

come in search of it. The design of the campus clearly shows how its

planners had wanted the world to be: wide empty bicycle lanes and bus lanes,

empty buses hence and forth. Totally crammed paid parking lots with electronic

signposts "FULL" in front, in between spacy grass fields that nobody ever uses

except the extensive fleet of motorized lawn mowers ... and even

sheep, at some places. I considered I might move towards and around in

Uithof cheaply and with carefree parking on a sheep, but wait ... could not even

a donkey or a horse do the job ... ecology and all that ... turds would contribute

to the global warming we need to survive the upcoming end of the

interglacial ...

"Physics"? To the university security officer engaged in writing number plates of illegally parked cars

that word

not ring a bell, but he did give me a quarter of compass that held, in his

opinion, an above-average chance. I managed to park. Legally. Large distances

from car parks to venues made me lucky with the

foldable bike I routinely keep in my car, but it would get stolen a week later.

I entered a building. Its signpost featured the building's name, that of someone I never heard

of - not was I ambitious to - but nothing else, in particular: not what could be

found inside. An exiting student apologized for not knowing

the whereabouts of physics: he was in informatics. I asked the muscular Arabic receptionist for the

physics department, but his face made clear that both the term "physics" and the

word "department" needed more explanation (where in the latter case I made no

progress trying the word "faculty").

"Well you know", the muscular Arabic receptionist told me, "This is the beta

building".

"That's not so bad at all", I replied "physics is pretty beta.

But is there any staff up here?"

"Staff ...", the man repeated with some

hesitation.

"I mean the office rooms of the people who teach here".

"Oh

yes, cross the hall and go up".

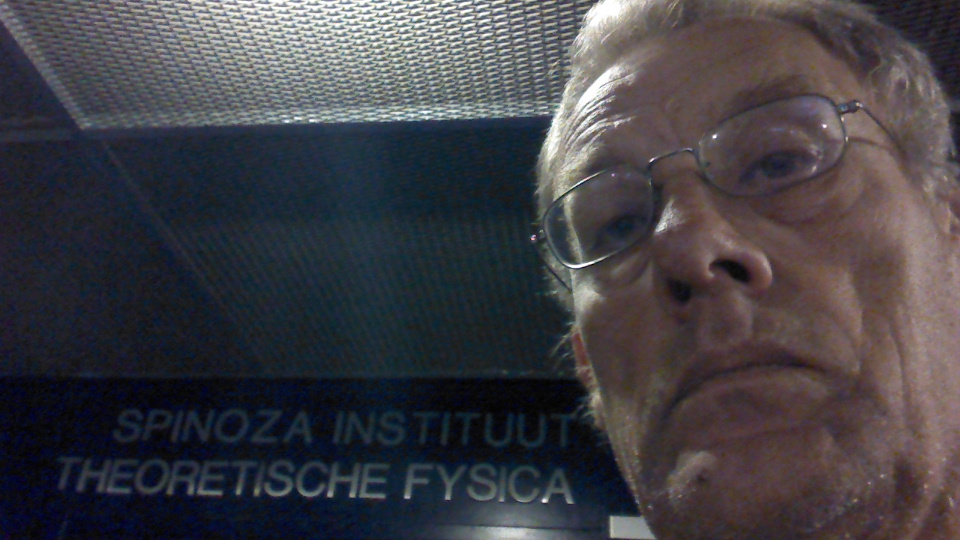

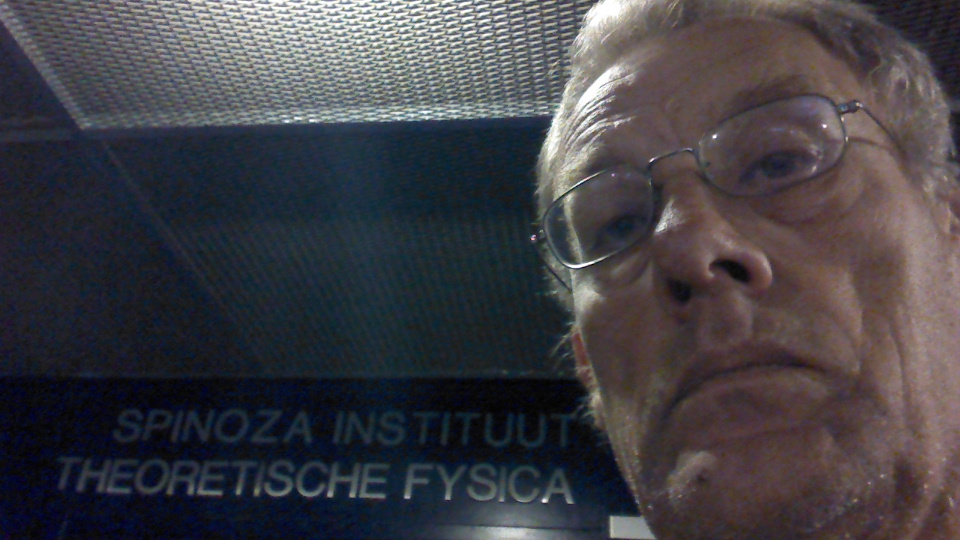

... I thought I was wrong: which physicist in his senses would associate

himself with a man so mistaken in his physical ideas as Spinoza, who, MIND YOU, lived

under Newton, so could easily have learned the physics of his time ...

I first thought I was dreaming: which physicist in his senses would

associate himself with a man so mistaken in his physical ideas as Spinoza, who

live when Newton's works reached Holland, who could easily have learned decent

physics instead of sticking to outdated Cartesian crap of a universe totally filled

with very fine particles, with no gravity, so they can only push each other and

form kind of twisters, small and big. Yes, he really believed such twisters

pushed the planets round en kept pushing himself against

the surface of the earth.

... trotting up: police arrest wing colours and hardware, physicists should be locked up firmly, seems the opinion ...

... blue darkness, blind doors ...

... Top floor: Spinoza Instituut ...

Behind that door I suddenly was in a bright comfortable top floor

unit with lots of roof light. A top research institute in physics. Spacy rooms,

though usually shared. In some, people were typing, in others two or three were

talking matrices, tensors, equilibria and filling chalk boards with wide

gestures. One thing was clear: if I would be given a desk here and allowed to

ask any question arising while studying relativity, I would be done in a few

days. The other: I did not belong here. These guys and girls were too good. All

around thirty, no

Dutch people either, except for the manager who kindly named

the building

where they know all about bachelor teaching.

Thank you.

Would not want to have missed this short digression.

... Homing in on target, my foldable bike did not mind me to stay away long ...

The "Buys Ballot" building was surrounded by bicycles of the

encouraging type: the ones with those locks of a price equal to the bike itself. And the reception

staff knew the room number of Els, the manager of

physics courses. Els gave me all data of my mechanics course, and a staff web page to

find those data next time.

... reception knew Els' room, she helped me out ...

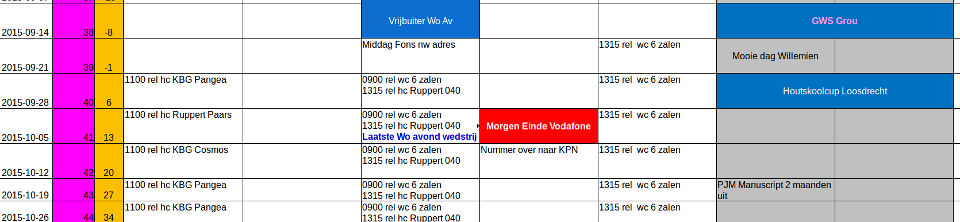

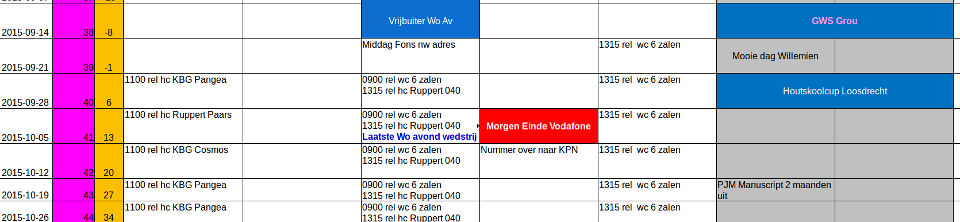

Not long after I returned home, my schedule sported signs it had not

seen for 16 years (blue is

12footdinghy competition sailing):

... Last

time my schedule sported this type of shit was December 1999 (but then even

worse: as a lecturer) ...

They had already started some weeks ago, but classical mechanics

(Newton, Kepler) had been done as well, most of which should be familiar to me.

So, the next Monday morning my alarm clock unchained me, I arrived

early, students told me what books and what lecture notes were used, and what is

the floor and room

number to buy them.

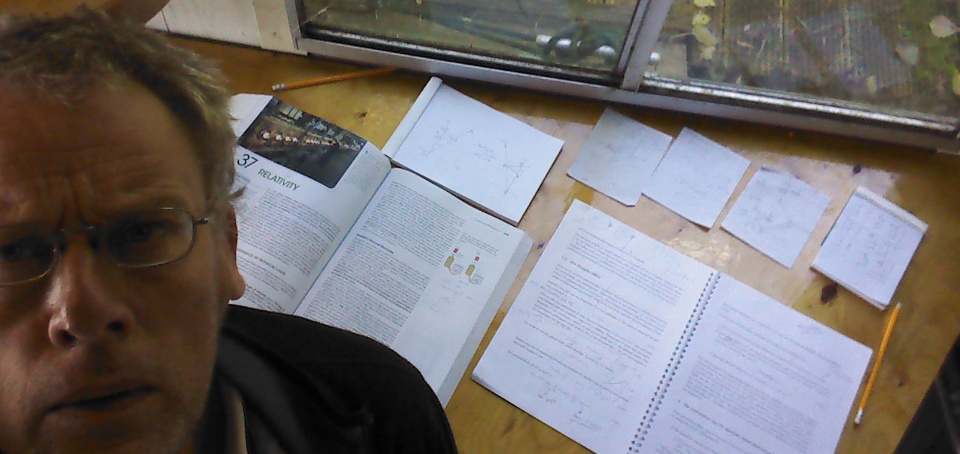

... this is serious!

...

There I sat, taking blackboard shots every one of which seemed to

require hours of work at home. Students are updated by a digital "blackboard" of

which I of course have no login. Well, by now I should have enough. I now realized why my search for my target had been a bit

erratic: I had accidentally taken a shrewd unused inroad over a campus security

officer, muscular Arab receptionist, Spinoza and Els. Smartly circumventing the

university's web welcoming page's "virtual sleeping coach" and "anti-teasing

program", I inadvertently managed to squeeze my notoriously oversized body

through an

unmonetized mouse hole entrance! I saved a value of at least some sizeable boxes of excellent Cuban sigars,

very agreeable smoking while covering paper with math (and then throwing most

them in the dustbin).

150 audience or so. Astronomy and physics bachelors. At face value

I seemed the only black student. Among these 17 and 18 year olds there were one or two

half African, quite some Asian, even more Arabic, everyone speaking Dutch. By far most

students were white and

Dutch, but clearly from all strata of society: here selection had been on brains

only! What a relief hearing them talking functions and equations in the

intermission instead of the ordinary adolescent bullshit.

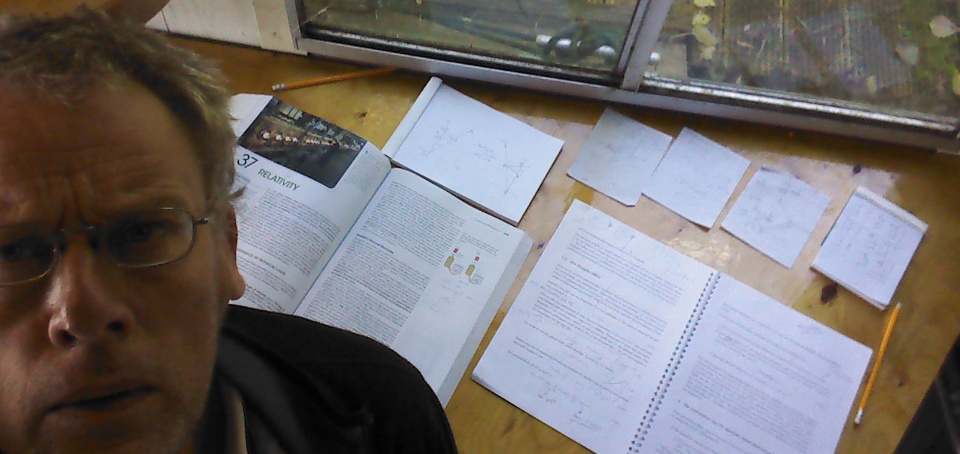

... On

September 28, 2015, I starting to cover paper with math ...

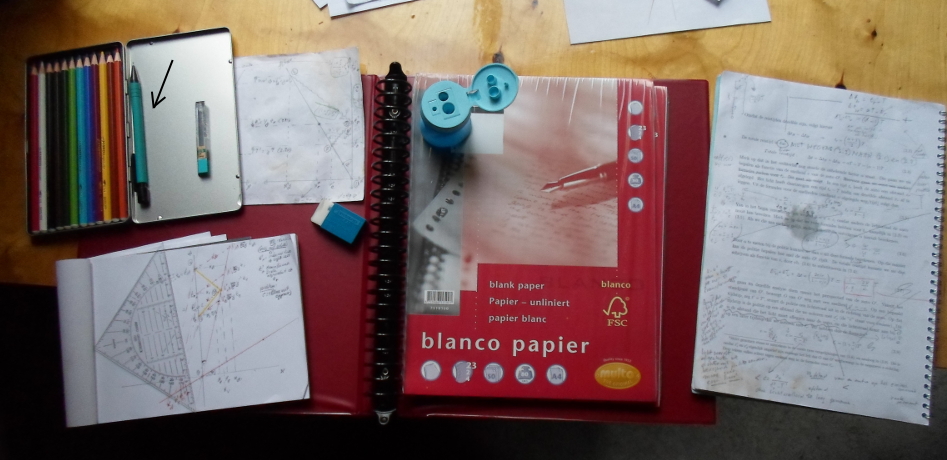

... old habits revived: non-digital hardware use ...

Since I last used non digital studying hardware twenty years ago (I lost my

last books in a

tornado on Lake Victoria, without much regret: all on internet now) the quality of colour pencils have

risen, multo-ring handling has become even more comfortable, pencil sharpeners

have further improved, geo-triangles are thinner and more flexible and there still

is replacement filling for my beloved carbon pencil (left at arrow) I

kept on me for over 15 years living in the

Alps, Africa, and wandering with my

Kangoo microcamper from

Inverness to Marrakech.