Bert hamminga The Claim of a Theory <planned Control questions>

The epistemological question is: what exactly do people believe who come up with this theory? Are they trying to claim the truth of something? If so, the truth of what? Or do they have other intentions? If so, what intentions?

Some economists claim they are after truth (but often only partial truth the theory, Friedman), other economists (Aumann) claim that economic theories have purposes different from truth. Let us do truth first, because it is the simplest.

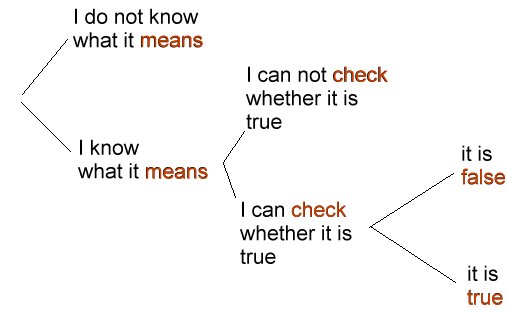

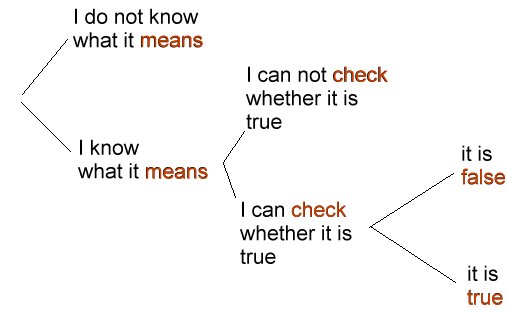

To judge whether something is true you, first need to know what it means, and second, find out whether you can check it.

What does it mean?

We first need to know what the letters p, Q, D and S mean. Price, quantity, demand and supply? That is insufficient to understand the meaning..

The philosopher notes that concepts (quantity demanded, quantity supplied, price) are introduced. The schedules suggest empirical hypotheses being formulated: supply goes up with price, demand goes down. How could this be tested, thus finding corroborating instances or falsifications? From the S and D schedules one can read off what consumers and producers would supply and demand if prices would be such and such. But many producer's and and consumer's reactions to a certain price never realize because such a price never occurs at a market. Prices can only realize if producers and consumers agree on some price and actually make a transaction. If not, these reactions are not observable. Schedules testable only by non observable events are untestable.

A way out is to assume that intended reactions to a price would realize if the price occurs. Then by questionnaires one could register intentions of individual producers and consumers. Each one could be asked to draw his (her) own schedule, and the results would be something like this:

Figure 2

Now one could, at each price, sum the intended supply to obtain an intended supply curve and the do the same with intended supply and arrive at something like figure 1. If supply turns out upsloping and demand downsloping, this could be regarded as a corroborating instance, and if not, this could be regarded as a falsification. Any falsification could be disqualified by maintaining that agent's answers on their intended supply in a hypothetical situation does not coincide with what the agent actually would do if the price would really occur.

This could give us a test of the assumption that the consumer's and producer's intended reactions coincide which their real, observable reactions: if the summation of the intended schedules of figure 2 yields an exploding cobweb, and the market in question shows only signs of gentle fluctuation, then apparently market parties do not really react as the said they would. This would falsify the assumption.

Are such notions of falsifiability, inspired by the doctrines of the philosophy of science methodologically relevant to economic theory? That is not a simple question. Economic theory is traditionally of a deductive nature: traditionally, the economist starts from certain assumptions, defends them as plausible assumptions, and then proceeds to derive theorems from them. Theorems are considered interesting if they are unexpected, novel, not evident, giving fuel to a debate on the economy, at odds with certain established views on the economy and the like. This is explained in more detail as Deductive Model Exploration, but here are some first examples:

Example 1: Adam Smith, one of the founders of economics in the 18th century, spends some pages to convince the reader of the plausibility of the assumption that entrepreneurs invest in the most profitable industry the can find. He does the same with the assumption that if more of the produce of that industry is brought to the market, its price will go down, and if less, it will go up. From this he deduces that if some industry yields, as a result of high prices, a more than average profit, this will attract investments withdrawn from other industries. These will increase the industry's production, thus lower the price of its product thereby lowering the industry's profit. The striking conclusion ("theorem") is that the profits of all industries in a country tend equalize. For more explanation of this example click Adam Smith's Invisible Hand

Example 2: Many simple and instructive examples of the procedure of deduction in theoretical economics can be found in a classic and still higly renowned book by Paul A. Samuelson called Foundations of Economic Analysis, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1947. A lot of his deductions in this beautiful book proceed from the assumption of stability: he assumes (pp.262-3) that normally markets are like the left type of figure 3 rather than the right type. From that he proves mathematically the theorem that an increase in demand (a rightward displacement of the demand curve as a result of, say, a change in consumer taste) will definitely lead to a rise of price. In this book he intends to show by many examples how mathematical deduction can lead from plausible assumptions to a meaningful theorem.

Many famous results of economics are called theorems: the Heckscher Ohlin theorem, the factor price equalization theorem, the Modigliani Miller theorem. Often the are called effects: the Keynes effect, the real balance effect, but this also refers to theorems.

The assumptions from which theorems are proven are of several different type. Firstly, there are basic assumptions characterizing the "research programme" or "paradigm" involved. A group of economists proceeding from a shared set of basic assumptions is called a "school" or "current". Terms like Neoclassical, Keynesian, and Monetarist refer to such schools. Secondly there are application assumptions needed to employ the basic assumptions to some specific field of application, like consumer behaviour, international economics, portfolio investment, the labour market etc. In all these fields of application one can be a "Keynesian", "Monetarist", "Neoclassical economist", etc. Finally you have special assumptions, usually of a technical nature, often highly simplifying assumptions needed to keep control over the mathematics of the problem and be able to derive the desired theorem. Take the first version of the Stolper Samuelson theorem stating that if, for instance, as in the US, labour is relatively scarce, the workers will absolutely benefit from any tariff on imports. Stolper and Samuelson had to assume that the country imposing the tariff is infinitely small, and thus has no influence on world market prices. That is an example of a special assumption. Not much later, Metzler stated the conditions under which the same is the case when there are two countries, neither of them infinitely small. That is an example of relaxation of a special assumption.

After the introduction, starting in the 1940's, of more and more sophisticated techniques of statistical estimation in economic research, this traditional approach was challenged by some modern economists, most notably Milton Friedman in his seminal article Friedman, M.(1953) "The Methodology of Positive Economics", in: Essays in Positive Economics, Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press. In this article, he defends the position that theories should not be judged by the realism of their assumptions, but by the accuracy of what he refers to as their predictions. See also: The Friedman Controversy . His key example is the assumption of profit maximation. He opposes the idea of judging this theory by studying decision making procedures in firms. The theory, according to Friedman is not designed to explain such procedures directly, but to explain price formation. If price formation is predicted correctly from the assumption of profit maximation, even empirical falsity of this assumption should not form an inhibition to use it.

Friedman's position suggests that it is not relevant to ask oneself how one came to "believe" in the schedules of figure 1, but instead should make a theory out of it that yields predictions. Suppose for some good, you have quantities sold and prices for each day during a certain period. The observations of each day are represented by points in figure 4.

Figure 4

How to explain these observations with the help of demand and supply schedules? One could think of a stable supply curve and a demand curve that is different each day. Each day, equilibrium would then be at a different place, and the observations of figure 4 would mark these places.

Figure 5

The data set would trace out the supply curve, its parameters could be identified. About the demand curve, no further information can be obtained. There is "falsification" of these assumptions if the observed points insufficiently approach a straight line, but then other types of curves could be fitted. The idea of empirical progress in the sense of Lakatos could be illustrated by imagining that the hypothesis is tested that the demand schedules of is good, say ice cream, depends on the weather, especially the temperature. If additionally temperature data of the days in the dataset are added and low temperature observations are found in the down left side, high temperature observations are found in the upper right side of the graph of figure 5, then the hypothesis seems corroborated, if not, it is falsified. However, also remember the theory-dependency of these conclusions: only prices and quantities are observed, yet the economist infers he sees a stable supply and moving demand curve. As soon as this is called into question, any talk about corroboration or falsification of the temperature hypothesis becomes meaningless.

Friedman's article triggered a hot debate, his article is still quoted as standard and seminal, but the mainstream of theoretical economics remained unambiguously deductive: trusting on basic assumptions that are firmly considered to be plausible, and working deductively to conclusions that might seem less evident but as a result of correct deduction from plausible assumptions gain credibility.