DME in Economics

Control questions

190210

Theoretical economics deals with abstract models. There is no perfect model for any

real world phenomenon. Hence, for every abstract model, there is an agenda consisting of

desired removals and additions of features. What theoretical economists do is studying the

properties of these abstract models by means of mathematical analysis.

Theory development it proceeds by mathematical deduction and proof. The

logical form of a proposition of economic theory is:

{C1,...} IT

That is, a proposition of economic theory proves some interesting theorem IT

from a set of conditions {C1,...}. To a model belongs

- a set of desired IT's and conditions

- a set of undesired theorems and conditions

The task of changing the model such as to get rid of the undesired features while

retaining or even extending the desired ones is called deductive model exploration

(DME).

There has been quite an extensive discussion among economists about whether one should

judge the theory by the realism of the conditions or the truth of its implications

(interesting theorems IT). This is known as the Friedman

controversy. In practice, economists work both ways, and for both ways employ a number

of different methods.

Economists use the terms

"theory" and "model" in different ways. More on this.

Some examples of interesting theorems derived by economists from specific sets of

conditions are

- Consumer behaviour: the Law of Demand

- International trade: the Heckscher Ohlin Theorem, The Stolper Samuelson Theorem, the

Factor Price Equalisation Theorem

- Economic Growth: the Harrod-Domar theorems on the relation of investment and growth

- Finance: the Modigliani Miller theorem.

Every student of economics is being taught such kinds of theorems, they are the actual

substance of the teaching of theoretical economics. In the realm of comparative statics,

interesting theorems usually say whether some endogenous variable of the model (often

equilibrium price, or equilibrium quantitity traded) moves together up/down with some

exogenous variable (like weather temperature) or against it.

Different types of conditions

At their birth, the theorems are usually proven under extremely simple, or

abstract conditions. There are a number of ways to classify the conditions needed to prove

a theorem. The simplest classification is the following:

- Hard core conditions specifying the basic approach of some research programme

(school, current) of economics (think of classical, neo-classical, Keynesian, Monetarist)

involved. Any such school or current uses these condition in every field of

application (like consumer behaviour, labour market theory, monetary theory,

international economics etc.).

- Application conditions, used by a research programme to employ its basic theory

for the explanation of phenomena in some special field of application. The standard

application conditions of the neo-classical classical theory for international trade

are, for instance, that production functions are equal in all countries but available

factor endowments (labour, capital) differ -relative- in quantity.

- Special conditions. The third set of conditions is born out of necessity: to

prove the desired interesting theorem, hard core and application conditions are usually

insufficient, and the gap must be closed by special conditions. These usually

have a mathematical technical nature. A good example is that usually nothing can be proven

from unspecified production functions. The mathematical problem can be brought under

control by making an assumption like linear homogeneity of production functions. Once this

is seen to allow the proof of some theorem, research centres around the possibilities to

relax such strong special conditions.

- Field. In shaping, in early phases of research, a mathematically manageable

model, usually the dimensions of the ideal economy scrutinised are set to limits. For

instance, in international trade, there are only two countries, producing only two types

of goods with the help of only two types of factors of production. There is no tax, there

are zero transport costs etc. This defines the ontology or field of the model.

Strategies of theory development

The basic set up of the different types of conditions and some first key theorems is

done by the founders of a "research programme" or "school" of economic

research. Some names of such founders are Adam Smith (Classical Economics), Marshall,

Jevons (Neo-classical economics, micro-economics), Keynes (Keynesian macro-economics) and

Friedman (monetarist macro-economics).

Once some interesting theorems have been proven in some field from

some strong set {C1,...}of conditions, there are number of ways

to proceed in the research programme:

- Proving established theorems (theorems already proven by existing old reserach

programmes that adherents of the new programme want to show is inferior).

- Finding new interesting theorems.

- Field extension: you can put more of the relevant things that you know exist in

real economies in the ontology of your model (for instance: from two factors of production

to three and to any arbitrary number). This is called field extension.

- Weakening of conditions: you can you can check whether all conditions used are

really necessary. May be some can be relaxed.

- Finding alternative condition sets: there might be alternative condition sets

from which the theorem can be proven as well.

- Deepening, or finding conditions for conditions: special conditions

with unclear economic meaning could be scrutinised by considering them like theorems, and

finding out whether they can be proven from theorems with a clearer economic meaning.

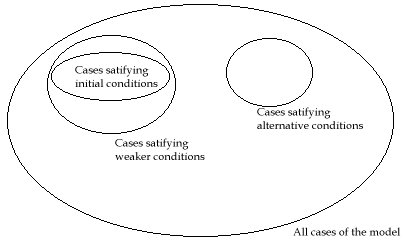

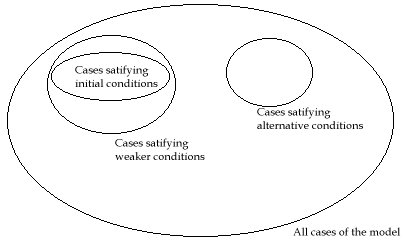

Finder weaker or alternative

conditions means that you discovered additional cases of the model where the theorem

holds (see picture right). The research work described is deductive and mathematical. How

do theoretical economists judge to what extent a model is a good approximation of existing

economic systems? In the natural science, a common strategy is empirical testing: finding

some real situation in which the the conditions of the theory are satisfied, or creating

such a situation in an experiment. Predictions should come true, if not, the theory is not

yet good enough. In economics, there are few possibilities to test by means of controlled

observation. Economists have the following alternatives:

Finder weaker or alternative

conditions means that you discovered additional cases of the model where the theorem

holds (see picture right). The research work described is deductive and mathematical. How

do theoretical economists judge to what extent a model is a good approximation of existing

economic systems? In the natural science, a common strategy is empirical testing: finding

some real situation in which the the conditions of the theory are satisfied, or creating

such a situation in an experiment. Predictions should come true, if not, the theory is not

yet good enough. In economics, there are few possibilities to test by means of controlled

observation. Economists have the following alternatives:

- First, and very often, the plausibility of the conditions used is discussed,

referring to general facts of experience. Profit maximisation

is defended by stating that in pondering alternatives, an entrepreneur will choose the

most profitable one, and those who don't, would be out of business fast. Is this an

"observation"? May be yes, but one of a very general kind. The Keynesian consumption function is defended by pointing at the

rationality of economic agents to let their consumption be checked by their income, and to

maintain that, though this might not hold for every individual, it will hold for the

aggregate consumption resulting from the decisions of all consumers in a country. By these

plausibility considerations, non-evident claims like the multiplier theory of investment

gain credibility because the are derived from plausible assumptions. Plausibility, in

these two and in many other examples, is derived from introspection: you are

asked to think of what you would do yourself if you were an entrepreneur, if you

were a consumer whose income is changing.

- Second, work is done to derive a plausible theorem (like the Law of Demand) from a given set of conditions (with the

neo-classical utility maximisation as a basic core). There, a core is considered to be a

satisfactory tool for explanation only if some key "evident", or plausible

truths can be derived from them as theorems. At a somewhat greater distance from the

actual theoretical programme is theory evaluation by means of acquiring data

relevant to the theory. For example, conditions might be evaluated by questioning

agents whether they feel they behave the way supposed by the conditions (one can ask

entrepreneurs whether they maximise profit). Or, the theorem might be compared to

data (the Heckscher Ohlin theorem implies that a capital rich country like the United

State exports capital intensive goods, and the Leontief paradox resulted from trade data

indicating that the reverse was, under certain assumptions, the case). If data acquisition

leads to conclusions at odds with theorem, conditions or both, a change in the assumptions

on how the data relate to the theory is undertaken rather than an abandoning the hard core

of the relevant theoretical research programme.

Finder weaker or alternative

conditions means that you discovered additional cases of the model where the theorem

holds (see picture right). The research work described is deductive and mathematical. How

do theoretical economists judge to what extent a model is a good approximation of existing

economic systems? In the natural science, a common strategy is empirical testing: finding

some real situation in which the the conditions of the theory are satisfied, or creating

such a situation in an experiment. Predictions should come true, if not, the theory is not

yet good enough. In economics, there are few possibilities to test by means of controlled

observation. Economists have the following alternatives:

Finder weaker or alternative

conditions means that you discovered additional cases of the model where the theorem

holds (see picture right). The research work described is deductive and mathematical. How

do theoretical economists judge to what extent a model is a good approximation of existing

economic systems? In the natural science, a common strategy is empirical testing: finding

some real situation in which the the conditions of the theory are satisfied, or creating

such a situation in an experiment. Predictions should come true, if not, the theory is not

yet good enough. In economics, there are few possibilities to test by means of controlled

observation. Economists have the following alternatives: