"Ma mère, quand il ... " Swann, Cottard, de Norpois.

"Cottard is on leave, that's a pity", my mother said when we planned to invite M. de Norpois for the first time. "And we lost contact with Swann, it would be quite forced to suddenly invite him now".

My father did not share the regret about Swann, but he'd liked to have had Cottard. This might surprise, but Cottard had risen from mediocrity in the years passed and Swann, since he had been married to that odd Odette got even boring to his old friends, with trite conversation.

Swann, who formerly could so elegantly stay silent about his invitation by Twickenham or Buckingham Palace until a friend pleased him by mentioning it in company, and then could utter himself so charmingly modest about it, nowadays boasted loudly about the wife of some sous-chef of cabinet who had come to visit his new partner. His former life style might not exactly have been free of boasting, but of the subtle kind. Now it had acquired the ridicule of, say, an admired painter who stopped extending his oeuvre to go into gardening and henceforth tries to score off his company with details about the proper cultivation of tomatoes and onions.

No, then Cottard! Outside his medical expertise he formerly might have appeared to say the least somewhat fatuous, but in his trade he now was considered top of Europe. Doctors with health problems of their own would readily postpone their conversations on Nietzsche and Wagner and head for Cottard.

Moreover Cottard had turned inside out, like people let their tailor do with a stained suit. The cordiality he displayed in his youth now had become invisible, and in turn he got a bossy air that fitted him perfectly. And then his irony, above all in the hospital, served with a poker face, bystanders of all ranks choked with laughter.

Then the marquis de Norpois: financial expert. Before the French-German war he was plenipotentiary, in high esteem of Bismarck. After Seize May his connections stayed well enough to remain the man to cope with serious international nuisance. Republican ministers in such cases liked to shock by sending an aristocrat like de Norpois, for instance in the crisis of the Egyptian debts. With him, they did not have to fear for games or lack of loyalty. He simply would never endanger his image of distinction, for he knew all he needed for his power base: a good name in his own noble circles, political influence, a literary or artistic reputation and vast wealth. In de world of commons, wherever one sought the company of the nobility, he picked talents with political and artistic influence, able to sharpen his image and further his interests up to rich marriage connections with his own family.

In the Commission, de Norpois always sat next to my father, who meanwhile had been congratulated from many sides for the friendship that de Norpois had honoured him with. My father himself was surprised too.

My mother had a taste for different kinds of intelligence than that of the marquis, she thought of him, even though his opinions could be quite unorthodox, as old fashioned in manners. But she thought it her marital duty to genuinely share her husband's enthusiasm for his new friend, so tried not to think it ridiculous when de Norpois, when encountering her somewhere, would throw away his fresh cigar before lifting his hat. She did not realize the marquis had developed his manners with great care to fit his diplomatic career and could not simply shake them off when at our table.

"Le premier dîner que ... " la Berma, Gilberte and my literary ambitions.

I, myself, still a child, playing on the Champs Elysées, burned for long with desire to see la Berma, the actrice, but my parents opined - though countered by my grandmother - theatre to be detrimental to the decent education of a young man. But M. de Norpois, my father told, had pleaded for me.

After I started a habit of somber trotting through the house for want of seeing Gilberte who was on holiday, my mother surprised me by suggesting to go. The marquis had turned my father, formerly not used to shun irritating Grandmother by calling theatre "useless", like a leaf in the wind and even had to silence my Grandmother, who was against it for fear for my health.

That was only the beginning: my father had talked to M. de Norpois about my future, in which he liked to see me be a diplomat, not meeting much enthusiasm from my side, since I feared Gilberte could not join me on my travels, so I preferred to be a writer. My father reported that M. de Norpois, irritated by the Republican scum that had conquered the diplomatic ranks after the fall of the Seconde Empire, had chosen my side again: nowadays, respect, freedom of action and independence would be better in reach in a literary career than in the embassies! An accidental coalition, but it made the marquis my hero before I even had seen him.

My father turned on this issue too, told me to write something, that he would invite M. de Norpois for dinner so I could talk to him, even started his to-do list for boosting my literary career in his influential circles.

Full of joy that I could stay with Gilberte I set out to "write something", but got decisively frustrated. Doubts, yes, tears of despair stacked upon the sadness Gilberte was far, mixed with the consolation soon to see la Berma.

Every day I checked the theatre billboards. For years already, la Berma only played modern pieces I could not relate to. Would she ever do a classical piece? I was close to total despair when finally I saw an announcement featuring two acts of Racine's Phèdre that I knew very well. Generally, to me, a classical play was like those towns and villages I venerated: outside that realm nothing was real. So Phèdre it would be. Free of worries to misunderstand content I would be able to concentrate on her acting.

"Le médecin qui me soignait ... ". Green light for la Berma.

The doctor had advised against theater visits. The pleasure would not weigh against the resulting medical misery. But such an argument could not convince me, for to me this was not a balance of pleasure and pain, but the acquisition of truths more real than the world around us, deserving unlimited suffering, death not excepted.

While all days I was practicing the different intonations in which la Berma - referred to in Bergotte's booklet as plastic nobility, Chistian penitential robe, Jansenist paleness, princess of Trézene and Kleef, Mycenian drama, Delphian symbol, sun myth" - would stammer the immortal «On dit qu'un prompt départ vous éloigne de nous» - and bring me in relieving tears about Gilberte, gone off on holiday, my parents had deserted back to the doctor's camp.

But not did I despond.

And after some days of demonstratively depressed sauntering round in the house, aided by the blessing effect of the opinions of the marquis de Norpois in matters relevant to the issue, my side of the balance obtained a tiny overweight.

Permission. A breakthrough.

But with the freedom came responsibility which triggered fear in turn: what if I got terribly ill? My parents deeply worried? Never see Gilberte again?

"But if you are really worrying about it, I could not go", I told my mother, in turn also practising her new role, that of reassuring me and make sure I would enjoy la Berma without inhibitions.

Thus I got a new, romantic, but sad task on my shoulders: to forget my fears and go to the bloody theater to please my dear mother.

In the end I had only one decent reason to go to la Berma: to get it over with.

And so I would really go. With Grandmother. Mind you, on the very same day that the marquis de Norpois would dine with us for the first time, Françoise personally to les Halles to select the steaks like Michelangelo the marble in the Carrare mountains.

"Sans doute, tant que je n'eus pas entendu la Berma ... ". la Berma, finally!

The evening had come. On the dark square of the theatre, the bare branches of the walnut trees shone in the light of the gas illumination.

And there they were, the receiving theater staff, checking the tickets and guiding people to their places, that staff on which depended the choice, the career, the entire fate of the actors and actresses, while somewhere up in the building some director was busy facing the accomplished facts.

In dealing with our tickets staff nervously looked at everything except us to see whether la Berma's instructions reached novices in their ranks, whether the claque knew they should not clap for la Berma, that the windows would be open as long as la Berma was not on stage, and absolutely everything closed, up to the smallest door when she entered, that a bucket with warm water should stand at an inconspicuous place to help putting any remaining dust down.

And lo! Her coach arrived. Horses with long mane. She alighted, hidden in her fur, sent, while grumpily greeting her fans, some of her entourage to check whether the seats of her invités were all right, whether the temperature was good, to report who was in the boxes, what the usherettes were wearing, since all that formed, it seemed, her very own outer garments, on the proper shape and position of which it would depend how she would be able to express her talents.

The play got preceded by pieces of comedy, so long and of such a poverty that I nervously asked myself whether la Berma after such a boring plethora of cheap performance would still be willing to take to the stage.

But yes, finally Phèdre started off. Though I knew perfectly well that Phèdre herself would enter the stage only later, the lady entering stage was so gorgeous that I felt sure she was la Berma. The second lady entering was so much more beautiful, herself, and everything she was wearing, and had such an elevated diction, that I knew I had been wrong: this was her.

Then, however! A lady appeared from the curtain at the back of the stage who raised a fear in me worse than that of all those usherettes who were swiftly closing all windows, that they inadvertently would forget one, a fear that the sound of a single one of her words would be contaminated, if only by the soft cracking of an evening program, or that some applause for the other two actresses would affect her concentration. I even judged - and in doing so surely outdid la Berma herself - that the hall, the public, the actresses, the piece, yes, my own body no longer should serve any other purpose than reverberate the inflexions of her voice, and my feeling of total overpowerment made me understand that only now I was facing la Berma.

Well and then I found she did not at all have the intelligent intonation and beautiful diction as the other two actresses. I listened to a play I read a thousand times, I knew it by heart, and to that she added exactly nothing. She talked too fast, and monotonous.

Yet, at the very end, my first feelings of admiration arose. They got triggered by the enthusiastic, almost wild applause by the spectators at the end. There I felt the radiation of la Berma.

And the harder I joined the frenzy by applauding, the better la Berma seemed to me as an actress.

Happy to have found, though only at the end, a reason for the superiority of la Berma, though suspecting it would not explain this mystery better than that of the Mona Lisa, or the Persée de Benvenuto, the exclamation of the farmer: "Still, beautifully done, all gold, what a work!", I shared, with ardour, the crude wine of popular excitement.

"Je n'en sentis pas moins, le rideau tombé, un désappointement que ce plaisir ... " Home for Françoise's first dinner with M. de Norpois.

Then home, where for the first time I would see the man who gave this turn to my life, dining with us for the first time: the marquis de Norpois!

He rose, shook my hand, and started, while routinely confirming his reputation as a brilliant diplomat, to check me from all sides.

He asked about my schooling, my own studies and my taste; what I thought was good, what I judged as less, all, for the first time in my life, in a way suggesting that my opinions could be helpful to others, instead of, as I was used to, triggering immediate measures of correction. But in this deeply interested posture he froze so absolutely, became like a statue, after which, every time he suddenly got back into motion, I got kind of shocked by surprise.

When I told him what I read he froze in a jealous posture, suggesting I was privileged to have the time for all that.

He himself, he said almost with regret, had followed his father's career, diplomacy, though he had steered the pen to write two books, one about the sense of infinity at the East shore of Lake Victoria, and the other about the unrivalled repeating rifle of the Bulgarian army.

Thus one could observe once more - he said this so subtly that I can't remember his words exactly, but it roughly seemed to boil down to the following - that it were not only muddle-heads and schemers who got so close to the limelight and that even in the Académie Francaise he was favourably referred to. And he would consider what he could do for me.

The way the marquis conversed about literature made me conclude it was a great deal different from what I came to think of it in Combray. As related, I had accepted my total lack of talent as an author, but M. de Norpois' observations on the trade made my last remains of pity about it disappear.

My father took me aside and said "Just go visiting him one time one my behalf, he surely will have good advice". My nervous feeling forcefully to be crimped as ship-boy on a cargo sailor subsided when my father wanted to discuss his investments with the marquis. Aunt Léonie's heritage got on the table as well, all for me, I did not know she loved me so much.

And so I got saved by the landing on table of a heap of stylish printed paper.

I knew my father was a skeptical about my kind of intelligence as my mother was of that of M. de Norpois and that it was only his blind love for me that kept me out of trouble. Since he knew my drafts for the piece he had ordered me to write for the marquis had all landed in the dustbin, he now asked me to find a little poem I wrote in Combray. I gave it, but when M. de Norpois returned it he said nothing.

My father shifted to the theater visit I just returned from. M. de Norpois embarked upon a eulogy of La Berma in the style of the newspapers.

My quest for truth overpowered other considerations that might come up in conversation and I simply fluttered the dovecotes by confessing I got disappointed.

"Disappointed?" my father said, a bit loud, with raised eyebrows, worried about the impression this would make on the marquis, "how can you say that you did not find it marvelous? Your grandmother told me you did not miss a word of la Berma!"

"Mais oui, I made a big effort to find out what was so special in her, she is very good b ... "

"If she is very good what more do you want!"

"What surely contributes to her success", the marquis said in my mother's direction, for he saw it as his responsibility as a guest to draw her into the conversation, "is her choice of roles. That is what makes her deserve her reputation. Never mediocrities. This time Phèdre I see. And this comes back in her costumes and play".

And since I actually did not want to be disappointed at all, I said to myself: "It was awesome".

"Le boeuf froid aux carottes fit son apparition, couché par le Michel-Ange de notre cuisine ... " Françoise's steak enters.

And there they came in! Françoise's cold steaks. On big transparent blocs of jelly. An historical moment, for after the death of her former madame, my aunt Léonie, and Françoise's entering in our service in Paris, she still was an awesome cook but she somehow had lost that aspect of miracle. Now, sensing my parent's nerves and excitement when the marquis had accepted our invitation, she had, this very day, found back her old mysterious fire as it had burned in Combray. And the ambassador did not fail to notice it.

His remarks were embedded in an abundance of other interesting points for discussion. I had a rough time trying to understand why this was so utterly ridiculous and that was of such great value, and so little was somewhere in between, but my general conclusion was that repeating what everybody says is, in diplomacy, not a hallmark of inferiority.

"The newspapers wrote that you had a long conversation with king Theodosius during his visit at the Bavarian court", my father said.

"Yes, one evening at a concert, the Eastern king, who has an excellent memory, saw me and a member of his staff came to ask me whether I could follow him to greet the king".

"Are you satisfied with his visits?"

"I am delighted! He is doing very well, especially considering he

is still young"

And the marquis said a lot more about international politics that I decided not to withhold for my readers of La recherche. After all it is always better to let someone make a fool of himself than to have him outsource it to you.

After that, the conversation shifted to travel, then to holydays, to focus on Balbec, where the M. de Norpois, of course, had been as well.

I went for a test: "The church of Balbec is beautiful, isn't it, monsieur?"

"Well, it is a nice church, but you can't compare it to the cathedrals of Reims, Chartres, and, in my view the pearl of them all the Sainte-Chapelle de Paris".

"But", I shrewdly asked, "the church of Balbec, isn't it partly Romanesque?"

"Yes it is Romanesque, a bit of a cold style announcing little of the elegance, the phantasy of the Gothic architects who work on the stone as if it's lace. But if on a day of bad weather day you have nothing to do you could go there".

"Est-ce que vous étiez hier au banquet des Affaires étrangères? ... " Diplomatic genius inadvertently offends my family's recently reinstated Hinduism.

"Have you been at the banquet of Foreign Affairs yesterday?", my father asked "unfortunately I was prevented".

"No", M. de Norpois answered with a smile, I have to confess I went in rather different circles. I dined at a lady you might have heard of, the delightful Mme Swann".

My mother managed to suppress a shudder and anxiously looked at my father, knowing that his reaction to severe shocks always took a bit more time. But her next emotion came rather quickly: curiosity to know what the company of the marquis had been.

"Heavens, well ... it looks like mainly gentlemen come there, there were some married men as well, but their wives were al indisposed and had been unable to join", the ambassador said with a naughty smile.

He added "I have to say there were quite some women, but they were more, let me say, from republican circles than from Swann's. I have to say I did sense from that side a distinctive sweetness towards Mme Swann"

"Well, who knows", he went on, "it may once be a political or literary salon. Swann is embarrassingly vocal about invitations of him and his wife by people you would not expect a man like him to boast about. I know him from his earlier days, I wonder, and I have to laugh a little, when at the end of such an evening he does his utmost to please, say, the director of Post and his wife, shows extreme gratitude for their visit and asks whether his wife would be allowed to visit his one time. But he does not seem really unhappy. In the years before his marriage he got haunted by some blackmail, not seeing his daughter after doing something the mother did not like. But of course she can no longer do such things now. And everybody thought that if she got her way and they would marry, hell for Swann would break loose. But see, the opposite happened! Yet one hears a lot of contemptuous jokes from many sides, but, well, she is not the kind of wife that would suit everybody, but this Swann is far from stupid, and if I am not mistaken she really loves him. I do not wish to deny she has her whims, but so has Swann, if you hear what is said. But she is grateful to him, and against all expectations became as sweet as an angel."

"Ce changement n'était peut-être pas aussi extraordinaire que le trouvait M. de Norpois ... " Digression concerning events of the meantime: indeed, though you might suspect to have started reading an apocryphal section of this series of volumes, Swann did in fact marry Odette.

The first volume of La recherche should, I hope, have prevented that now you doubt the brille of the marquis even to the extent of dismissing his claim of Swann's marriage.

No, no, Swann did not love her anymore but he married Odette de Crécy.

It was less odd than it seemed to the marquis. One could also underestimate Odette's awareness of the intellectual side of Swann, and of the other side she was almost the only initiate, and understood that its value was worth the effort to get it more in the open, also through his work.

And did Swann worry about his image in high places? Not at all. Even before he met Odette he had started to be bored there, and after she had detached him more of them he had lost all ambitions of intercourse with exactly that large chunk from where those jokes came that M. de Norpois referred to, for neither did he need them for anything any longer.

By the way, had this not been so, his decision for this marriage would have been even more meritorious, since in such cases one opts for a less flattering situation for the sake of purely private considerations. That is why infamous marriages tend to be the most respectable.

Swann's thoughts in this respect were largely limited to one person, the princesse des Laumes, now duchesse de Guermantes. But this had nothing to do with snobbery. And Odette would never feel threatened by her: too high to be a competitor, such a woman with, from Odette's perspective, perhaps only the Virgin Mary above her.

But her he wanted to be able to visit with Odette and his daughter. Stronger even: when Swann, in the preamble, considered marrying Odette, his thoughts had often dwelled on visiting the duchesse de Guermantes, in total privacy, to show Odette and Gilberte to her.

Exactly that would happen only after Swann's death (which may have been a good thing after all).

"Je me mis à parler du comte de Paris ... " But we are still at dinner.

But we're still dining with M. de Norpois. I raised an issue about the comte de Paris, pretender of the French throne Philips VII and asked whether he was not a friend of Swann, on whom I wished to keep the attention focused.

"He sure is", M. de Norpois said, and he knew an anecdote about Mme Swann and Philips, who had encountered her some four years ago on a railway station in Central Europe. His suite, knowing her, realized that the comte should not be asked for his opinion, but when the subject spontaneously popped up later, the comte's expression had indicated that he had judged the view far from disagreeable.

"And what is your own impression, monsieur l'ambassadeur?", my mother asked, of course out of pure politeness, though I did sense some curiosity in her question.

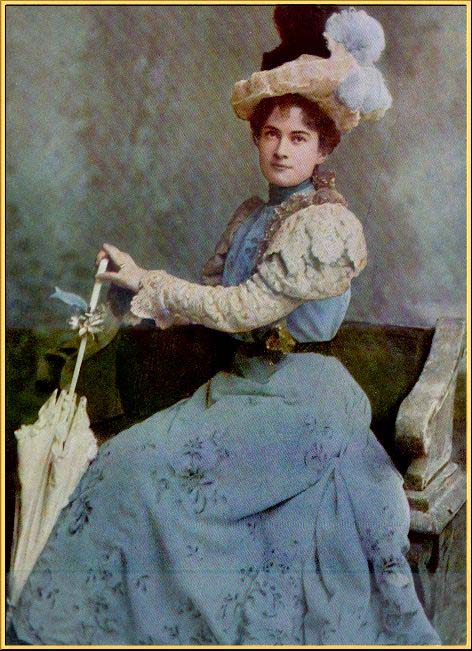

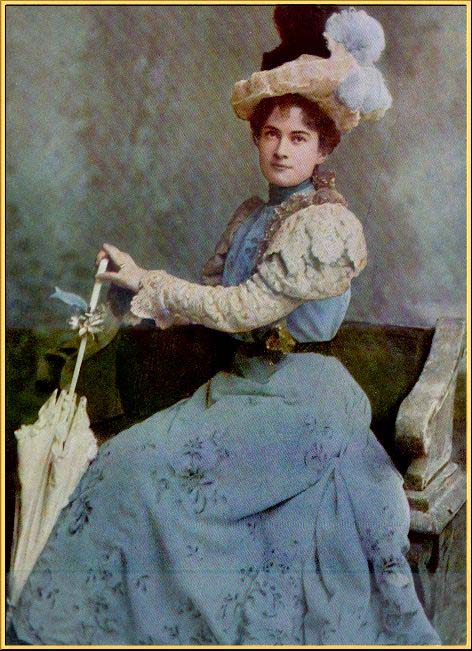

With the energy of an old connoisseur who expresses himself prudently but decidedly about everything, M. de Norpois replied: "More than excellent!", bursting, as the subject required, in a short little laugh that yet extended for a while, during which the blue eyes of the marquis got a bit moist and his nostrils with their tiny red veins started trembling a bit. "She is more than charming".

"Was there also an author by the name of Bergotte, monsieur?"

"Yes, he was there, do you know him?". The marquis looked at me with the piercing gaze that Bismarck admired to much.

"My son does not know him but admires him a lot", my mother said.

"My God", M. de Norpois exclaimed.

I sensed heavy clouds drifting my way. I wished I could dissolve. Why on earth did my mother say something like that.

"Such a writer I call a flute player. And his play is not bad but insufficiently seizing due to an excess of embellishments". The plane is dearly missed. Powerless, aimless. Moulded fundamentally wrong, or rather, there is no fundament at all. Esthetical capers. In contemporary Europe, where so much is collapsing and so many borders change, there is more than enough useful work for authors, but now ... " he turned to me, "I gain a better understanding of those lines you just gave me to read. Well, it shows that every young person occasionally imagines himself as a poet, and, above all, you see the bad influence of Bergotte, though at your age you cannot yet imitate him since you are insufficiently acquainted with the literary tradition that he is inspired by".

"With all of which I do not wish to deny", the marquis went on, "that the books are infinitely better than the man himself. His speech is even boring, which one cannot say of his writing. And he is vulgar".

Even though I had already completely written myself off as an author, this review of my few lines and their inspirator devastated me once again. I did not doubt: the marquis was right.

But he did turn out to have had a small stand off with Bergotte as well. Bergotte once had visited him in Vienna when he was France's ambassador there, with a letter of recommendation by the Prinzessin von Metternich, wanted to register and be invited.

"I first thought, well let me do it, if it should be, but then he added that his travel company would be included in the intentions of the princess. I was still young and thought, well, I am still a bachelor myself and not a pater familias, let me not block this, but when I came to think again how much attention there is in his work for the smallest of moral scruples, and then arrive in Vienna with who knows what kind of woman, that such a self-proclaimed author's hand is shaken by some highness who then wonders how on earth it could have occurred to me as ambassador to ... in sum, I did not reply to his request. The Prinzessin von Metternich did go for an exhortation, but I ignored it, I thought let me redress that when I see her again". All in all, I will have thoroughly spoiled his Austrian holidays, so I was rather unsure whether Bergotte was charmed seeing me that evening at les Swann.

"Swann's daughter, was she there as well?" I asked.

M. de Norpois had a thought, then: "O, like fourteen, fifteen years old? Yes she is introduced to me as Swann's daughter. You know a lot about that family".

I play with her at the Champs Elysées, I like her very much".

"Well, now ... , she looked very charming to me. I have to confess thinking she will not reach the level of her mother, but in this case this should offend nobody".

"I prefer Mlle Swann's figure, but I do admire her mother as well. I go to the Bois de Boulogne just to see her there".

"But I'll tell them, they will be delighted".

It seemed natural to M. de Norpois to bring me under the attention of Gilberte and her mother. I got overwhelmed by such a strong feeling of closeness to him that I feared I would go and kiss him, even feared that my urge, though withheld, was visible, and, years later, found out it indeed had been.

"O, monsieur" I said "I you would do that it should not even suffice if the rest of my life I would keep showing my gratitude, and that life would be yours! But you should know I have never been introduced to Mme Swann." While saying all this I saw the marquis looking away for a moment as if he held internal consultations. A little later I understood what I had done: now I had made clear to him how much value this had to me, it occurred to him unlikely he would be the first to the mission, which would mean other attempts had failed and he first had to find out why.

And indeed, les Swann would not hear from the ambassador how much I would like to be invited - which would turn out to be much less of a disaster than I suspected at the moment.

"Quand M. de Norpois fut parti, mon père ... " After M. de Norpois had left.

After M. de Norpois had left my father threw a look in the newspapers, while I continued my frantic attempts to axiomatize the grandness of la Berma, for I perfectly realized that a lot of work had to be done to reach that lofty aim.

In trying so I did follow the beaten track, at least one often hears that in the communal life of that enormous amount of ideas in our mind, the one idea that makes us most happy sucks most of its power, that it lacked when still standing on its own, much as a parasite, from another idea that apparently was within reach but of the existence of which we are not aware, and often will never become aware of the rest of our lives.

Meanwhile my mother was sitting with some regret that my father had abandoned the idea of my diplomatic career. I suspected her to hold such a diplomatic education as more beneficial to my ability to control my nerves than this literary activities.

My father did not defend literature by argument, or by the authority of M. de Norpois, but as "my" choice, something that at my age one could begin to regard as a something fixed.

I stayed silent but felt despair about the impossible load my shoulders now got charged with. Now my preferences, if I was to believe my father, got fixed, it felt as if I had started to really exist as finished object with a definite shape and mass, launched in a orbit that now was fully subjected to the laws of nature. That I now was just the passenger of that object and all I could do was to wait and see where I would end up, since such things I had read more than once in our garden in Combray. And then such an author could suddenly skip entire decades, and there you would see, down on the very same page, where such a person had finished. Which usually was a far from enviable spot.

But, my father conceded, apparently to my mother, that M. de Norpois is a bit conventional. My mother, however, refused to be on the record for such an opinion, to the delight of my father now inspired to add some remarks about the agility of the marquis in the meetings of the Commission.

In full concord my parents set out carefully to conclude that what the marquis had told them about his evening at les Swann had absolutely not disqualified him in any respect.

"Mais de tous ses mots, le plus goûté, ... " De Norpois en Françoise satisfied with each other.

The words of the marquis for Françoise ("chef of the first order") were the ones repeated most often in the family, even years later, and whenever she witnessed it she claimed she could not "hold her face". How remarkable this is you can only appreciate when you remember how in the final years of her former madame, Aunt Léonie, who was gradually losing her mind, Françoise could sadly and ashamed play for the cheating maid she got accused to be, without loosing her firm grip on the household - and without ceasing to love her madame.

I did have a contribution in Françoise's kitchen myself by requesting the rabbit to get killed smoothly so it would not suffer too much. Now, after the marquis had left, Françoise assured me that it had the best and quickest death in the world, and died in total silence.

To me such a silence seemed, for a rabbit, after all not a chicken, not very surprising but Françoise protested: "You come again next time, they scream quite a bit harder than chicken!"

Françoise had accepted the compliments of the marquis with the excited, and - for this special occasion - intelligent facial expression of an artist whose work is discussed.

My mother said: "The ambassador said one nowhere eats cold stake like yours".

Françoise, with a modest face to pay tribute to the truth, retaliated in kind: "he is a good old one like myself".

"But how is this possible?", my mother, who had sent Françoise on apprenticeship along some top kitchens in Paris.

"They fry to fast and they fry them separately", Françoise explained, "But first the meat should get spungy and drink the juice. And tonight's jelly was not entirely mine, but soufflé had a good amount of cream".

So the conversation continued for a while about those top Paris kitchens where she had been sent to learn, during which her reviews typically were of a kind that would be unrecognizable to the Paris newspaper reader.

"Quand vint le 1er janvier, ... " A new year between me and Gilberte.

On new year's day, in Paris at the time, one made short visits to all relatives. My physical weakness had prompted my father to design a logistics of shortest route, disregarding seniority, my mother panicking when at the very first visit we encountered an acquaintance of a senior relative who would now no doubt get air of it.

After returning home I left again with Françoise and sent a letter to Gilberte that was carefully edited yet ready for quite some time. I wrote her that our friendship of the previous year would be scrapped, that I would forget my grudges and disappointments, that we would build up a brand new friendship, so solid as to be indestructible, that I hoped Gilberte would mobilize some coquetterie to help preserving it in its full splendour and to promise issuing timely warnings in case of the tiniest unexpected threat, as hereby I would promise myself.

That done and posted, Françoise bought two new year's gifts: a photograph of pope Pius IX and on of Raspail. I bought one of la Berma.

I still played on the Champs Elysées. But no Gilberte. It became high time she would appear, for my loving staring far in the direction she would come from made my memory loose the fix on her figure. At last only the smile was left. Irritating. While I could at any time draw out the horse cart drivers and the sugar sellers. Would I have stopped loving her? Anxiety.

But one day there she was. And continued to come. Finally my image of her got fed again by the reality of the day. And not only hers: she always was reluctant and secretive when I expressed my admiration of her parents, but one day she burst in a nymphish giggle and said: "forget about my parents, they can't stand you!". In her estimation her meeting me had been regarded as a regrettable incident, and now they merely decided that interference would be overdone. My morality was doubted, my bad influence feared.

To the reader who kept oversight this may seem a bolt from the blue as it was for me, and offended me so deeply that I wrote a long letter to Swann and managed to convince Gilberte to deliver it.

That was counterproductive. Sixteen pages so deep from the bottom of my heart as those words by which I spoiled everything with M. de Norpois. Now Swann felt absolutely sure I was an underhand cheater. At our next meeting Gilberte pulled me behind the shrubs to bring the news. He had said: "This only proves how right I am".

How on earth could Swann doubt the goodness of my soul, and could not be brought to reason by this letter!

For at that moment I still felt perfectly sure that, smart as he might be, he was wrong.

Writing La recherche I decided that the exact content of my letter is no business for my readers, who, after all, should every now and then realize that even I appreciate some privacy.

But I can assure you that, in as far as I had, in the darkness of my sleeping room, occasionally doubted my own integrity, that uncomfortable feeling had totally been replaced by absolute certainty, pleasure and comfort after I had finished that letter and read through it once more.

Though I thought I would stick to this view of myself forever, fortunately this lack of prudent uncertainty did not last for long. When, arriving at the Champs Elysée, I found Gilberte hidden in a game, I sat down next to her and asked whether it would be any good if I went and talked with her father. She whispered back this seemed useless to her.

She said: "Here, take the letter. Come on, let's go, they gave up finding me". And her body attracted me so much that I said. Keep it, I'll try to take it from you". She held it on her back, and there we rolled round, Oh!, how lovely.

When I got the letter Gilberte said: "Let's do it again." But just before grabbing the letter, I had come, in my trousers, anxious she would have noticed it. So, though more in the mood for relaxation, I granted her request for reasons of camouflage.

The moist fungal air behind that littel shed reminded me of the tiny Combray "room of uncle Adolphe" which excited me, before I got depressed again for this skirmish made my absolute certainty about the error of Swann's judgment waver, while M. de Norpois seemed to be more right than ever: devotee of a flute player-author taken away, not by a Grand Philosophical Idea but by the smell of an old shed.

I was doomed.

Sure.

"Depuis quelque temps, dans certaines familles, ... " Ill again.

Superstitious mothers gossiped a lot about the Champs Elysée as a source of diseases, fortunately my mother was immune to it.

But I got a fever again. Lungs. The doctor prescribed alcohol, to the dismay of my grandmother, not mine. They'd rather not administer it so I had to couch and hawk with drama when I longed for a sip. Once I got it, I was again full of pity for my grandmother, whom it clearly brought in distress.

At last it got so bad that Grandmother herself went out for cognac when my breathing problems returned. My parents decided to call doctor Cottard.

"A strong laxative, milk. Nothing else. No meat, no fish, no alcohol", Cottard said, meeting a resistant pose of my mother, who believed in recuperating.

It looked like Cottard checked whether accidently he might have dropped his severe mask. Then, after concluding hadn't, he said: "I say things only once."

Neither did he humiliate himself by providing arguments. My parents did not follow the ordnances, and henceforth avoided company where they could meet Cottard.

After which my problem substantially deteriorated.

After which they tried Cottard's therapy.

After which within three days my hawking and couching was gone and I breathed normally.

"Un jour, à l'heure du courrier, ... " A letter - from Gilberte?

My serious illness had given doubt to my parents concerning the "health" of the Champs Elysées. It was discussed whether or not it was a good idea to let me go there again after I would be fully recovered. I went up and down the house in the pissed-of mode I was well known for, and the body language of, above all, my mother and Françoise was clear enough to know I ran my message home.

One day my mother brought a letter to my bed that had just arrived.

_________________________________

My dear friend,

I have heard you are very ill and no longer go the the Champs Elysées. Neither do I, for a lot of children get ill there. But my friends visit me on Mondays and Fridays.

Mama asked me to tell you that it would be the pleasure of all of us if you would also come after you recovered. It will allow us to continue the good conversations at the Champs Elysées.

Bye my dear friend, I hope you will be allowed to come and send you my friendship.

Gilberte.

_________________________________

I should have been ill for another two months after a letter like that.

But no.

And some more things did not happen. The letter, at first, failed to reach my soul. This was impossible.

Did my mother write this to boost my recovery, the way she put beautiful shells on the wet part of the beach sand to encourage me, as a baby, allow the seawater to come round me a little?

Despite all my doubts and unbelief, my brain got inspired to an entire theory of amorous movements that I resolved to deal with subtly and at great length when later I would write La recherche. And Françoise had profound suspicions concerning the ornamental G, supported by an i with no dot on it, as a result the name could be read Alberte.

Some time before, Bloch had visited me. Cottard, back in the field after the delayed, but astonishingly successful application of his therapy, was there too at that moment, ready with me, waiting for the dinner for which he was invited.

Bloch had just heard, he said, the evening before, that I was a favourite of Mme Swann. That could of course not be true, but since I thought he said it out of some kind of goodness, or to boast about his connections, I did not comment.

But while M. de Norpois, as related, had diplomatically stayed silent about my at les Swann, it had been Cottard, doctor of Odette, kindly disposed to me - and pitying me too - who, after hearing Bloch, had told Mme Swann about me and somehow, totally unaware of the complex situation, turned her around. And, well, she might all along, by her nature and history have been less upset by some possibly corporeal aspects of my youthful passion for Gilberte than her husband whom Cottard, in this way, dominoed as if for one time he had been a brilliant diplomat.

Alors je connus cet appartement ... " The impossible happens.

And so the impassible house-keeper of les Swann, at that door where you already would smell Mme Swann's perfume, miraculously turned into that very friendly man who welcomed me by taking off his cap.

And those first floor windows, above me, on that street, that had separated me from the treasure I longed for! Now I sat entire afternoons with Gilberte in that room and when a reception was going on, our two heads would appear looking down out of the opened window to see who arrived, one of those two little tails of Gilberte would brush my cheek, and we would be greeted by people who thought I was some nephew.

And if in the house I met one of her parents they were totally friendly and cordial.

At home I praised all stuff I saw in that house. Though I never had studied the subject I had no worries at all: everything should surely be enviable, though I reddened a little when my father turned out to know that staircase was "simply Berlier", that he had considered one of those the houses there for himself but had judged them too dark.

The thought that those houses would not be good enough for us was so unbearable to me that I decided not to have it at all.

My mother started complaining that I always returned home sick of tea and chocolate cake, but how could I refuse anything offered by Gilberte?

One day on which Gilberte and her mother both "received", Mme Swann, tired, she said, of all discussions about the Table of Gérôme, came to rest with us for a moment. Returning to her guests she looked at me over her shoulder, said again I was always welcome, and suddenly started about my "nurse". This turned out to be Françoise. I was astonished to learn that Françoise, whom I thought an impediment to closer contact with the Swanns for her lack of a chique raincoat and blue feather on her hat, was liked so much by Gilberte that her stories about her here at had been another weighty factor in the conversion of les Swann to my favour.

Then Mme Blatin, regular spectator of our games at the Champs Elysées, thought by me to be a possible trait d'union to les Swann: I heard nothing but reserved language about her.

Summarizing, I was lucky, and not a little, for having failed to walk even a single one of the ways I thought there had been to gain access to les Swann. In the end I would not even be surprised if monsieur l'ambassadeur marquis de Norpois, Bismarck's favorite, would have been totally incapable to turn the smallest thing around at les Swann. Françoise, Bloch en Cottard together had, all inadvertently, been the triggers that Gilberte had needed to get her way.

"Le royaume dans lequel j'étais accueilli était ... " More about the kingdom I gained.

My entry in this kingdom soon extended beyond the rooms of Gilberte. If I let my self be announced while she was not around, I got invited in. It could sometimes be deemed useful I had a word with their daughter to convince her of the use and importance of this or that matter.

I thought of the long letter I wrote to Swann to which he had not deigned to reply, and admired the impotence of mind, reason and heart to establish something that subsequently got settled by life itself, with the greatest ease, behind everybody's back.

The holiest room, Swann's cabinet, was for me not the most impressive. It somehow still breathed the sadness of his period of heart-brokenness (do not ask me how I knew). Neither could the great works of art, some of them by his personal friends, make me remotely feel the insignificance of my own person when bestowed the royal benevolence of Mme Swann, receiving me in her room, surrounded by three chambermaids, laying, smiling, the last hand at her appearance, always miraculous if before some event. Yes, insignificant, that is how I felt, all the more while I got called by a valet announcing that "Madame wanted to tell me something". My admiration had built up even before I arrived, going the long way through all those corridors smelling of her delicate perfumes.

When afterwards she was with her guests we heard her talking loudly and bursting in laughter every now and then - even if there were only two or three guests yet - just like her patroness Mme Verdurin always did when she "directed the conversation". In the range of expressions that in the course of time she had adopted one could find everything from language typical for the top of French nobility - via Swann - to poignant idiom of common people from her personal ambiance.

At the end of such an afternoon Swann's head could appear around Gilberte's door: "Is you mother alone?".

"No, there still are people".

"What, still now? One time the'll talk her to death. I forgot about the salon until I arrived in the street. I thought we had a marriage! And since I'm in my cabinet I heard the bell every five seconds until I had a headache. Who are still there?.

"Mme Cottard and Mme Bontemps", Gilberte replied disinterested.

"Ahhh, the wife of the chief of the cabinet of the ministry of public works!"

"Knowr husband worksatte minstry but f'got which" Gilberte said with a carefully enacted baby voice.

And her father ... "How you suddenly talk as if you're two years old again, my little clown, this monsieur is directing an entire ministry, in practice he is the man deciding what is happening there!"

Gilberte kneeled still a bit deeper down to her father: "Wow, that is quite something!", but she failed to break his serious face: "and he is an officer of the Legion d'honneur".

Odette obviously felt elevated by her marriage, while Swann had decided his loss of status, wherever and in whose eyes he would suffer it, would not be an impediment to worry about. But both regarded the new point arrived at only as a beginning.

Swann was like a chess player who, after having reached a position of boring superiority, had made the game interesting again by throwing off the board a sufficient number of his own pieces to be the weak party again and ... start working again, with all remaining means at the consolidation of his new position.

And that went with the loud advertising of every new social conquest, as a result of which the salon des Swann resembled one of those health resorts that hang the correspondences with high personalities at their walls.

"Du reste, les personnes qui n'avaient pas seulement connu l'ancien Swann ... " Properly viewed, Swann had not changed.

Thus every careful observer would easily see Swann had not changed. When in the melting-pot of old nobility, artistic brilliance and scholarship in circles around les Guermantes a rather embarrassingly simple-minded grand-duchess had to routinely be invited on social-practical grounds she would, after having left, be discussed between Swann and the princess des Laumes as "charming", "perhaps not dwelled at the bottom of the Kritik der reinen Vernunft, but with a certain sense of humour". Now Swann dealt exactly the same way with Mme Bontemps, who surely contributed to the "position" of Odette.

My parents perfectly understood what was starting to happen at les Swann and followed it with quite some curiosity - though of course from a decent Hinduistic-bourgeois distance.

When Mme Trombert turned out to have been recruited my mother said: "Ah, now there's a row of others ready to come". When she had seen Odette somewhere, she would say: "I saw Mme Swann on war path, some offensive against les Masséchutos, les Cynghalais of les Trombert!".

Those Cynghalais were Sri Lanka savages who since some time were on display in the Jardin d'Acclimatation.

My father, already discussing, granting the ends, the means of les Swann, confessed himself unable to grasp the use of Mme Cottard in the overall strategy, but my mother came to his rescue: somebody from the old times had to stay around to be told: "look at me now!", and, secondly, Mme Cottard was all over Paris and spread the word.

Unfortunately Odette's progress was limited to the official world; she had no success yet with the posh ladies. Which had nothing to do with the republican flavour of part of her salon.

Let me clarify this: when I was a boy, no respectable salon would invite a republican, and that was considered a law, eternal as that of oil lamps and horse drawn omnibuses. But eternity gets shaken every now and then. Even before my first communion posh ladies might risk, when visiting a salon, the scary encounter of an elegant jew. At the time I started visiting les Swann the Dreyfus affair shook things again: the Jew disappeared and the "nationalist" replaced him. At that time the loftiest salon was that of an Austrian fundamentalist catholic prince. But Dreyfus and with him his entire race got rehabilitated, moreover meanwhile the threat of war with Germany had increased again. Another shakeup. It became politically incorrect to doubt the loyalty of our French fellow patriots the Jews and nobody had ever been in that salon of the Austrian prince, as all others who never had been there could testify.

Every time after such a shake up, the new situation was regarded as fixed for eternity. When the shock of the telephone was over, the airplane remained a laughable phantasy and the past, especially the recent past, our philosophers of journalism told us, had been a sinful pool of political confusion, bad artistic taste and stray scholarship.

Also, Swann's image in his own family played a role in blocking Odette's progress. Before the affaire Dreyfus not Rothschild, but Sir Rufus Israels was the most powerful Jew of France. His family did the financial affairs of the princes of Orléans already for three generations. Lady Israels, Swann's aunt, was not regularly seen in salons. Swann honoured her little though he must have been her heir. But les Israel knew about Swann's contacts. The rest of his relatives had no idea. Every now and then they had the politeness to visit their "Cousin Bête", as they called him with a pun on Balzac

"Lady Israels, excessivement riche, disposait d'une grande influence ... " Under strict control of Lady Israels Paris blocs Odette's entry to the true posh.

Lady Israels, immensely rich, had used the influence she certainly had to prevent Odette from being received anywhere.

But there was a stealth deserter, le comtesse de Marsantes. She once had the bad luck that Lady Israels had herself announced just at a moment when Odette was visiting her.

The comtesse did not need to heed Lady Israel's ukases, but was coward as a hare and deeply ashamed.

Thus Odettes little breakthrough had been coped with promptly and effectively.

In the eyes of all those ambitious bourgeois snobs versed in aristocratic genealogy and trying to make their way in the faubourg Saint Germain Odette was an illiterate whore who should not think that perhaps she could be part of the circuit.

Neither did Swann seem particularly eager to force her in: a lot of her lapidary opinions were outright heresies from a mundane perspective and he never did anything about it. Even in the times he was in love with her, her lack of intelligence had not disturbed him at all, and he was interested even less in what she understood about the customs and ranks of the noble world. En that was, actually, nothing at all.

As a final stroke of bad luck for Odette, recently some salon hostesses had turned out to be whores and spies so the posh had turned a bit nervous and over-careful.

But Swann could not care less: the more stupid things Odette said in her jaunty aplomb the more he amused himself - while at the same time, if Swann did venture to add something sensible to a discussion she sharply corrected him, to Swann's secret pleasure.

Swann maintained a selection of old contacts in which he seemed to be led by the same artistic and historical motives that he had in collecting art.

And he loved experimental combinations. Once he thought it interesting to invite the duchesse de Vendôme with the Cottards, excited by his expectations of how such a meeting would work out.

But Mme Bontemps, with whom he shared his plan, did not receive it favourably. She recently had been introduced to the duchesse (for the totally different reason of fixing her more solidly to Odette's circles), and was far from eager to share her fresh pride with Mme Cottard.

To relieve Mme Bontemps' suffering she got invited to the occasion as well, so afterwards two versions of that evening went around, the Bontemps-version with the Cottards in a unsightly role, and the Cottard-version, in which the Bontemps featured as hairs in the soup.

And Swann split his sides.

"De ses visites Swann rentrait souvent assez peu de temps avant le dîner ... " Update on Swann and love.

With the vanishing of his love for Odette, that urge to bring rivals in the game to compete with her, gain leverage, or prove he did not love her anymore, had gone as well.

Using his professional skills in the field, he kept his new mistress outside Odette's awareness.

"Ce ne fut pas seulement à ces goûters ... " Mijn geluk bij les Swann

About my life at les Swann I resolved to digress, once writing La recherche, as Dante about the circles of heaven, for I dreamt of not, as most authors do, shunning the defiance to every now and then provide the readership with the satisfaction, not of readers' enjoyment, but of heroically performing the tough, repugnant and uninstructive job of moulding happiness in literal form.

I, my dear readers you have to face it: I was at les Swann like the innocence in paradise: even about those sinful urges of the flesh that Gilberte had triggered in me behind that shed on the Champs Elysées I had forgotten all - at least so it seems when I reread this episode of La recherche - so I did not have to fear Swann to assume a baron Thunder-ten-Tronck-posture that could get me closer than desirable to that unrivalled Bulgarian repeating rifle, glorious subject of that brilliant panygeric that almost had taken M. l'ambassadeur le marquis de Norpois right into into the Académie Française.

Those sudden little trips of Mme Swann that so sadly caused Gilberte's absence at the Champs Elysées turned into a joy for I got invited to join, and I even was asked which of the alternatives I preferred.

For such a trip I was asked to join their dejeuner, called "lunch" by Mme Swann. First I would look at our dejeuner at home, which was earlier, then, elegantly dressed, set off for les Swann.

Sometimes everybody there was still out. Once I got let in by a valet who led me through a number of large rooms and let me in a vide to wait for Mme Swann. My ears scanned, in the silence, for small signs of the advent of someone. The first time it was staff adding some wood to the fire. Then M. Swann. "What is this? Are you sitting here alone?" While shaking his head about his wife's lack of punctuality he took me to show his latest purchases. But I was hungry and could not concentrate on them.

Sometimes they stayed at home an entire afternoon. Then, before dressing for the evening, Mme Swann could put herself behind the piano in her peignoir. Thus I first heard the sonata of Vinteuil. The first time it sounded a bit confusing to me, but after two or three times that got better.

I resolved later in La recherche to dwell decently on the mental process of understanding music in a confusing essay out of which musical experts would no doubt conclude that I know nothing about it and at the time knew even less, but, whether I understood the understanding of the sonata, or just understood the sonata, or even neither, it mattered little to me, for the main thrill was to witness Mme Swann playing the piano. Her interpretation and touché seemed to me in an organic connection which the odour of her staircase, her chrysanthemums, her peignoir, in a mysterious unity infinitely superior to any prosaic world in which reason is capable to judge quality.

"Did you hear that little leaf hanging totally still in the dark?", Swann told me when Odette had finished. I hadn't, but neither had I been sitting so often, like Swann, on windless nights in garden restaurants near such trees listening to the piece. Had Odette realized how much closer this music was to Swann's heart than she herself, there would have been some consternation. But she would not even have understood it if somebody carefully set out to explain it to her.

"How it reminds me", Swann said, "of everything I had no attention for at that time! And it does not remind me at all of the rest, my worries, my loves".

That did cause one of those still leafs to whirl to the ground. "Charles it seems not very sweet to me what you just said", said Odette.

Swann, now realizing he had been slightly too clear, quickly covered his retreat with an ode to love, elegant enough to Odette, ironical enough to me.

When we went out I walked with my company with great pride, even more of the mother than of the daughter, hoping to meet all those people whom I suspected to not esteem me the way I thought I deserved.

That was all the more so when we met, and greeted according to the rules of the art, high nobility known to "us" with an exchange of words of fitting content and length, such as when near the Jardin d'Acclimatation we encountered Mme de Montmorency, princess Mathilde, a real niece of Napoleon I, imperial nobility, even asked for marriage by the Tsar.

But to be perfectly honest: in my view, nobody really could match Mme Swann.

"Faveur plus précieuse encore que ... " I meet Bergotte!

When once I got invited by Mme Swann for a "big lunch", with a lot of guests, she introduced me to someone she called "Bergotte".

Of course I had expected sooner or later to meet Bergotte at les Swann, but yet, his name sounded as a gunshot in my ear. I had no idea what he would look like (do not ask me how this had never come up between Gilberte and me). Barely managing to control myself I greeted him and got greeted by a young man, rough, small, disproportionately wide shoulders, seriously myopic, with a nose most closely resembling a snail-shell, and to complete the disaster, a thin little black chin-beard.

Everything turned before my eyes. In a split second, that grey wise old man with those grand and deep sentiments my mind, through the years, carefully had construed, had gone to dust, but not only that, for what now was dust had harboured, as a temple totally designed for the purpose, the splendour of an immense oeuvre, for which there was no place, no doubt about it, in this thick-set body full of veins, bones, ganglions with that snail-shell nose and that silly little beard. No way.

Curiously enough I did not die.

But what died was my conviction that life on earth would have been impossible without Bergotte.

Deeply disillusioned I knew nothing better to do than tie to this monstrous dwarf, as sort of a balloon, Bergotte's oeuvre, but now its size seemed to have shrunk to a scale making me despair it could ever take the air with its new ballast, small as it was.

At table my place turned out to be close to Bergotte's so I could hear him well. His talking seemed totally different from his writing, even when dealing with something he had written about. When he gained steam and started talking a bit like "my" Bergotte, I even sensed nothing at all of the sound, intonation and rhythm that his writing evokes, for, though at such moments he started to talk pretentious and coercive, it was entirely monotonous.

Whenever there was some sound variability in his voice when speaking, it had nothing to do with his writing. Totally different. I tried to explain it to Swann, who had known Bergotte from the times he still was a child between his brothers and sisters. He recognized the voice tonality I tried to describe as a characteristic of the Bergotte family. At first it seemed to me that it had not reached Bergotte's writing at all.

I this context, "Bergotte" means "my" Bergotte, as opposed to the general public's perception of Bergotte at the time. For "my" Bergotte senses and relates a mass of precise ideas such as you do not find at all when reading all those authors who adopted the "style of Bergotte". What was called à la Bergotte at the time was not at all the essence of Bergotte, I had concluded far earlier. That essence consisted of taking something valuable and true, from the heart, and then extract it in brilliant writing. That was the trade of the Mild Singer. He did so despite himself, since he could not help it he was Bergotte.

And once written down it showed as "à la Bergotte", as the woman looks after she has dressed herself.

A real genius senses some reality, which always is unexpected, a branch full of blue flowers shooting from the hedge in spring, at a place where things looked totally full already. Imitation, by contrast, is empty and uniform and provides the copiers only with the illusion to have made something that reminds them of a master whom they did not understand. The followers start paying attention when Bergotte writes about «the eternal deluge of appearances» en «mysterious shivers of beauty». But then you are too late!

When Bergotte talked you could get a glimpse in the kitchen that would not at all have interested the imitators à la Bergotte, for instance when he called Cottard a "float on its way to its equilibrium", or said about Brichot: "he has more trouble having his hair right than Mme Swann for depending on the situation it should make him look like a lion or a philosopher". Bergotte would never write such a thing for it was not "mild". But it was real Bergotte. My Bergotte.

In the end I discovered that the family-specific intonation of his speech did reach his writing: how every now and then for instance a euphoric sentence ended in sounds that reminded of the raw shout of joy he could end with when speaking.

In daily life, Bergotte was, like the rest of his family, not seen as refined or spiritual. They had, on the contrary, the image of being a bit loud, vulgar and even irritant in the way they made jokes that were considered partly as pretentious, partly fatuous. The truly brilliant was in what Bergotte did with it. Rolls Royce owners will typically look down upon a wooden construction on wheels, but when then it gains speed, goes up and takes to the air, at least the more intelligent among them are likely to change their minds.

As far as the á la Bergotte is concerned, even in authors almost proud to be different one sometimes recognized Bergotte for elements of his syntax had become generally used, certainly in literary circles. Nobody realized it was Bergotte.

By the way, as far as the final nonessential touch of writing it down is concerned Bergotte took a lot from a friend who himself never wrote something important.

Irritated by the generation of authors venerated when he was young, who used to virtually bury their observations under words he purposively antagonized them by writing: "See! A little girl with an orange shawl, that's nice!" And he hated them: Tolstoy, Eliot, Ibsen, Dostoevsky.

"Mild". That was Bergotte's keyword for the good in literature, I would hear him say: «Yes, yet my Chateaubriand is more the one of Atala than of René, I find it milder.»

If he got praised about something in his work he would say: "Yes that was useful". Many years later, after he lost his inspiration and, dejected, sent something to the editor anyway, he would mumble: "Yet useful for my country", turning unnecessary modesty in failed consolation.

Already at the time I met him he looked up to others for being, unlike him, members of the Académie Française or faubourg Saint Germain furniture.

And thus my ridiculously grave disappointment about Bergotte when first meeting him, had some aspects that stuck.

"Cela il le savait aussi, comme un kleptomane ... " Bergotte's worldly ambitions.

He perfectly knew, you could read it in his work, that genius annihilates the significance of your official position in the world. And what others told him about himself taught him he had that genius. But though he learned it, he failed to really believe it, so continued licking the arses of all those fatuous little authors in the Académie in order to be raised to their ranks.

And even that he understood, like the knowledge, so useless for a kleptomaniac, that stealing is bad. He, who so pregnantly described the value of simplicity had, by all means, to become part of the rich and powerful. On this aspect, M. de Norpois had been right.

And the heroes of his books, with the increasing finesse of their moral scruples during their loftiest deeds, more and more antagonized the man with the snail-shell nose and that shitty chin beard who wrote them down.

Not that he became undividedly weak and bad. Well, he treated his wife rudely, but once saved a poor woman who had wanted to drown herself, stayed all night with her and when finally he had to leave, left a good amount of money for her. Could it be that he had a similarly immoderate attention for the lives and characters of his books that nothing was left for himself? That he morally neglected himself by his overwhelming urge to care for his characters?

For I think he had dissolved into that poor woman as in one of the figures in his books. Not in her, but in an image in his mind. Even before a tribunal he would be unable to address the real judge of flesh and blood before him and instead would verbally draw images that would not move his prosaic audience for a millimeter.

"Ce premier jour où je le vis chez les parents de Gilberte ..." With Bergotte and the three Swanns about la Berma, Phèdre and M. de Norpois.

That moment where la Berma, in Phèdre, with elevated head and arm stood still for a moment in green light, which would, I thought have charmed me had it lasted a little longer, Bergotte interpreted as an element af classical Athenian sculpture from the golden age.

I eagerly added that to my industriously gathered collection of reasons why la Berma was a genius, though immediately with the regret I learned about it only now and not before the performance, when I could have built up a tension to look for the moment to arrive.

Bergotte disliked the green, but did not silence me who had liked it, like M. de Norpois would in such a case. And this was not at all because his opinion was of lesser value: the opinions of M. de Norpois were not open to discussion due to their total lack of reality.

Thus M. de Norpois was back in the discussion, who seemed warmly appreciated by neither Bergotte not Swann.

"Pour dissimuler son émotion, ... " Going back home with Bergotte.

While Bergotte started a conversation with Gilberte I wondered about the lack of inhibition with which I had told him my thoughts, and suddenly started to seriously worry that he might have thought of it all, most of which I developed when still much younger, in Combray, as not up to much.

A substantial amount of time later I was still engaged with these worries when Gilberte returned from Bergotte and whispered in my ear: "I am swimming in joy for you conquered my great friend Bergotte".

Bergotte lived near us and after the "lunch" invited me to return home in his coach.

"I hear you are often seriously ill", Bergotte said, "that looks awful to me, I sympathize with you". He went on "but I do not overdo it since I see you know the joys of intelligence, which compensates a lot of suffering".

This entire balancing operation felt strange to me. I answered: "No Sir, I do not know how to appreciate the joys of intelligence, I do not seek them and do not know whether I ever tasted them".

"Yet it must be so, is my impression"

He did not convince me, but I felt a small relief, as if even in my low self-esteem I got some breathing space. M. de Norpois had helped me in a beautiful dream about myself. But that had clearly felt as a dream. With Bergotte, with that conviction of his to know "my case", it looked like I just had to abandon my doubts, and should stop having enough of myself.

"Who is your doctor?"

"Monsieur Cottard"

"I do not know him as a doctor, but I talked to him at les Swann, an imbecile! Even if he is a good doctor for simple souls he should bore intelligent people so much that he cannot be effective. Three quarters of the illnesses of intelligent people are caused by their intelligence, a doctor should at least understand them. I mean, if you ate something wrong he will understand, but what if you read Shakespeare?"

"I recommend doctor du Bouldon, he is intelligent"

"That sure is a great admirer of your work". As far as Cottard was concerned Bergotte touched nothing in me.

"Swann", Bergotte said, "also could do with a good doctor".

On asking what was wrong with him, he said: "Married to a prostitute, fifty times a day sucks up to snakes of women who do not want to receive his wife, and up to men that had sex with her. And look at his face when he does it"

The malevolence with which Bergotte, to me as an outsider, spoke about a very old friend of his was as new for me as his almost tender tone when he addressed les Swann when meeting them.

"All this between us", Bergotte said, when he dropped me at our house. Later I would learn to answer: "of course", and not feel bound. At that moment I merely remembered my grandmother's reply to something like that.

She would ask: "But why then did you tell me?"

So I said nothing.

"Malheureusement, cette faveur que m'avait faite Swann ... " Back home after Bergotte.

At home my hope that my parents would start sharing some of my enthusiasm for les Swann quickly vanished. My father navigated again on the stars of M. de Norpois, now in my disadvantage: "Did he introduce you to Bergotte? Another thing we aren't spared of".

Bergotte's not undividedly positive view of M. de Norpois turned out for my father to be another proof that I was on my way to fall in wrong hands.

My parents, I judged, had so blatantly lost every contact with reality that I realized I would not even try to mend it had I known a means, but meanwhile I heard myself say: "He told Swann he thought I was extremely intelligent".

And thus my instincts, on their own, turned out to move M. de Norpois, who after a short silence was said to be "not always generous to people beyond his persuasion", just enough to make space for Bergotte. My mother proudly caressed my hair.

Even before this Bergotte-battle, my mother had told me I could invite Gilberte when receiving friends. But I did not dare, for, first, unlike Gilberte, my mother served, besides tea, always chocolate. I feared Gilberte would judge that common. Secondly my mother was not, like les Swann, always asking: "How is madame your mother?". Sounding her I did not find her ready to assume this habit.

And so I prudently opined I should postpone this operation for an indefinite period.

"Ce fut vers cette époque que Bloch bouleversa ma conception du monde ... " Bloch threatens the order of my opinions.

This was also the period in which Bloch made mince meat of my world view by assuring me that women always only think of sex, and taking me to a brothel. A third class establishment with ugly girls, bad furniture, but a sympathetic madam, with whom however, we did not engage in business.

After having been there a number of times I decided to give that sympathetic madam some furniture, notably the canape, from my heritage of Aunt Léonie. But when they had arrived, something started to haunt me and I never returned.

Only much later I realized that in Combray, on that very canapé, I had had my first ever skirmish with a girl.

I also sold the silver of Aunt Léonie. That was to keep financing my stream of baskets full of orchids to Mme Swann. As I come to think of it, generally in this period, I was mainly engaged in all kinds of gestures that could make me even more pleased at les Swann.

No wonder the first fruits of my authorship were painfully staying away. At home it was on everybody's mind, but nothing was said, except once by my grandmother, who regretted it immediately and promised never to do it again.

Mme Swann saw it differently. When I once declined an invitation in order to keep "working", I seemed to embarrass her. She raised the pressure by adding Bergotte would be there, as if she thought great literature was made by having the right contacts.

"Ainsi pas plus du côté des Swann que du côté de mes parents ... " Mme Swann's seeks my good but causes my demise.

And so I went, being again with Gilberte too. With her everything kept moving, for, though I had arrived at the stage of Love, there was always something new to long for. Every time I came home I found something new to tell her, that she absolutely should know on short notice for our entire friendship depended on it.

Thus putting the first hand at my oeuvre assumed the status of a secondary occupation, especially at times when Gilberte seemed a little less keen on seeing me return to her as soon as possible. I easily could go round that, since as for her parents I could never pay enough visits. They also thought I had a good influence on her. But I should have been more careful with that.

The last time I visited Gilberte she was just preparing to leave for an afternoon of dancing in a house where I was unknown, so she could not take me. With a sharp "Gilberte!", Mme Swann ended her daughter's preparations for departure and, though she said the rest in English, while she talked I felt myself burn to the ground in Gilberte's mind.

Gilberte had to stay, and in as far as she talked to me it was to keep the conversation going until I would decide to leave.

I tried to get to the point somehow saying she was not nice.

"You're not nice yourself!"

"I am!"

"O, yes of course, you think yourself nice".

"What am I doing, say it, I'll do everything you say".

"That makes no sense, I can't explain".

"I really loved you, you will understand that one time", I said and had the courage to decide I would leave and never come back. But I did not say it, she would never have believed it.

Furiously, bowled over, mortally wounded, I marched home where I judged I could only survive by returning right away. But I did not want her to grab the victory, and gave myself to the writing of a great many confused and inconsistent draft-letters.

When that fire had burnt out I went back. The house-keeper of les Swann, who liked me, not only reported her absent but, much worse, added he could call some other staff member as a witness in case I would not believe him. Had I had the hope not to have spoiled it all with Gilberte, now I would have lost it: her mood had reached staff.

Well then, I would not return, I promised myself again. She would surely write to excuse herself. And after that I would still not come. I was going to prove I could do without her.

At home I started waiting for her letter. This entailed some peaks of tension every day at the moments of the postal deliveries. But in between there was no calm, for of course she could use another delivery service.

And such remained the situation. I lapsed into phantasies about what I would do when she wanted to see me again. I would agree and then, just before the moment agreed, write a letter saying that unfortunately something had interfered. That would give her the feeling that I did not care a lot about our relation anymore. Or in my phantasy I wrote the letter she would write me, may be even bring it herself.

When I knew Gilberte was out I visited Mme Swann. That was terrible as well, but I forced myself to believe this would make Gilberte think better about me. Mme Swann had told me for long that she would like me to visit her outside the routine of the salon, her "Choufleury" she would call it. That now was an excellent reason to do that, though of course I only thought of Gilberte.

"Et très tard, déjà dans la nuit, presque au moment ... " The deeper layers of the meaning of late tea.

Such a visit to Mme Swann started as a late night walk through dark streets, for to Mme Swann tea had a special meaning. When she told a man "You will always find me up late, visit me once for a cup of tea", she did so with a subtle and soft smile in a slightly more English accent than usual, as a result of which the addressed company was inclined to receive the message with the mimic of a certain weight.

From the style of her previous life as a top prostitute she had kept the attention for things that only come to the forefront in the intimate atmosphere between man and woman, like in-house garment, furniture, ornaments and flowers. This explains her love for orchids and generally everything that gets revealed, not when a women dresses herself, on which the part of feminity that considers itself decent is focusing itself, but when she gradually distances herself from the items she is wearing.

From October on Odette was very keen on keeping the habit of what was then called by its English expression five o'clock tea, for she knew that Mme Verdurin's salon, with which Odette was now competing, had gained solidity by the certainty that the hostess would always be there at that time.

And on such occasions she beat Mme Verdurin with quite a margin, between her orchids and never in the same peignoir (every single one was for me by itself a reason to go for "tea" at Mme Swann)

And thus there often were others and I listened, my mind on Gilberte, with a half ear to the conversations in order to make some polite contribution at a proper moment.