Marcel Proust

DU COTE DE CHEZ SWANN

Première partie

COMBRAY

Crtd 14-06-05 Lastedit

15-09-14

download pdf

- I -

"Longtemps, je me ...". Dream, consciousness, and memory.

Often I fell asleep early. Once I had put my book aside and blew the candle I was gone. Then, in my dream, I would be straight back in the book, as a church, a music quartet or the quarrel between Frank the First and Charles Quint.

When waking up a little later, it would last a while before I could liberate myself from the book and reacquire the status of its beholder. Then I started to see and I saw it was pitch dark. Trains whistling far away reminded me of the extent of the world.

Then I would see light under the threshold. Morning! The end of the suffering! But no, the light got blown out. It was not even midnight. Hours of suffering to go. No solace.

Sleeping in again I usually only had short dreams, often featuring fearful experiences from far earlier days, like when my great-uncle pulled at my earrings. Then I would wake up, remember the day the rings got cut off, and slept again, with my pillow, for safety, all around my head.

If the pillow ended up next to my head sometimes it became a woman and I got kissed. If she looked like someone I knew, all details arose until she was the one. Slowly it would reside and she would disappear.

Waking up after longer sleep I would have no idea of time. If I had slept deeply, I would not even know where, who and with whom I was. This latter would come back first, after which I rebooted step by step.

The key thing was to locate my legs. That would allow me to position the walls and the furniture. But which ones? They could be taken from sleeping rooms of my past, and then I would think: "O, I fell asleep before Mama had come to kiss me goodnight", and presumed myself to be at my grandfather's, who died years ago. But everything would be there around me, like the superb old ceiling lamp, in all detail, and the more I woke up the better I would remember it.

Then, even if house showed no life yet, I did not want to sleep again, and enjoyed remembering all about my life in Combray at my great-aunt's, in Balbec, Paris, Doncières, Venice.

"A Combray, tous ...". Swann junior and my family's Hinduism.

In Combray they had bought me a magic lantern. To cheer me up they put me in my room and dimmed the light. But that made my room seem strange, like I was in some hotel. Moreover, this sweet Geneviève de Brabant succumbed in her slandering by this terrible Golo, projected on that same wall, and at dinner time I fled in my Mam's arms, relieved that it had not been her, while I severely scrutinized myself for Golo-type urges that I should liberate myself of with the harshest of means.

After dinner I had to part with my mother again, who would sit and talk with the rest in the garden. Or, with bad weather, inside, while I was not allowed out myself, to the indignation of my grandmother who was of the opinion that I would never become a strong boy like this. My father did not even reply to my grandmother while my mother restricted herself to the role of the loyal and modest wife, which prompted grandmother to enter the soaked garden for a walk. "O my dear, finally some fresh air", she would say to herself, redirecting her pique to the gardener, for everything was way too straight and boring. Quick-tempered little steps. Françoise, our maid, could be looking at her from the inside, her expression revealing full knowledge of how grandmother's dress would start looking in a minute.

My great-aunt, owner of the house, niece of my grandfather, was capable of luring my grandmother in if she thought it was enough. Then she shouted: "Bathilde, come to help keeping your husband off the cognac!". Grandfather, who was not allowed cognac, always got a sip from her. On that sign, Grandmother would storm inside and beg her husband not to take the sip, but he would take it anyway, and Grandmother would get out again, sad, disappointed, but with a smile ... about herself.

I had no clue it was a game. I could not bear witnessing it. As soon as I heard this "Bathilde, come ... " I sped up to the attic, for I was allowed to lock there, my refuge for reading, dreaming, tears and lust. And what I also was unaware of was that Grandmother spent the largest part of her fiery garden-thoughts worrying about my brittle health.

As far as disasters were concerned, there was one guaranteed at the end of every day: being sent to bed. Once lying, there was only one thing left to look forward to: Mama would come to kiss me goodnight. But it was hard to fully enjoy it, for when I heard her coming I already realized the sadness that would come over me once she had gone. So, the later she came the better.

Once she was back at the door to leave I really would like to ask for another kiss, but I knew that would make her angry. Dad thought of the whole bed kiss exercise as nonsense so I even had to be careful guarding my privilege. I knew what it would mean to loose it for if we had dinner guests she would not come.

Our circle of dinner guests in Combray was largely confined to M. Swann, who got invited less frequently since he married a lady that, in our house, was not discussed in favourite terms.

But Swann did also simply pass by some evenings. Then we would hear the bell of our front garden gate and one asked one another: "who would that be?". But it always was Swann and everybody knew.

My grandmother was the one to be sent scouting while my great-aunt countered the whispering tone the company had assumed by loudly proclaiming that such makes, on whoever is approaching, the impolite impression of being dealt with in confidence.

M. Swann's father had been an intimate friend of my grandfather, who had a repertoire of stories about him. At the death of his wife he had been inconsolable. At one point that day, my grandfather had taken him out to his park to have some fresh air. Suddenly, the old Swann got passionately moved by the beauty of his park and pond, to lapse back in his desperate sadness a moment later.

In the two years he outlived his wife M. Swann Sr. remained in utter saidness, often saying: "Curiously, I very often think of my wife, but every time but a little." This made me think of him as a monster, but to the judgment of my grandfather, which in this matter I trusted more than my own, and who since used frequently and with joy the expression: "yes, yes, very often but every time a little!", M. Swann Sr. had a heart of gold.

We did not know that M. Swann had taken off the world of his father, an exchange dealer, in what could well be deemed an ascension. He was a member of the Paris Jockey-Club, intimate friend of personalities like the comte de Paris en de prince de Galles.

Our ignorance stemmed partly from his discretion, but mainly because he was considered the son of his father, hence fully known. Bourgeous circles at the time had a kind of Hinduist approach to social matters, in which your family determined your status whatever happened to you in your life. We would not dare to ask M. Swann's about his, for fear of embarrassing him and we firmly believed that in our company he would shy away from greeting his friends.

In our view, M. Swann even had sunk a little from the level of his father, who, in Paris, would never have chosen to live at the quay d'Orléans.

M. Swann's conversation subjects were prosaic. He liked to speak of kitchen recipes, and got raised to the level of authority: when preparing a dinner for which he was not even invited, someone was sent for his instructions for the sauce gribische or the pineapple salad.

But he could, to the enjoyment of especially my great-aunt, relate amusing events, for which he invariably chose ones involving people we knew: the village pharmacist, our coach man, the kitchen aid, and in which he gracefully positioned himself as the one to be made fun of.

We knew he was collecting art, but among us experts there was little confidence in the result, even though my grandmother would have loved to come and see it, had M. Swann not lived at the quay d'Orléans.

When the sisters of my grandmother forced him on a judgment concerning a painting, he would ask almost impolitely little about it, merely, for instance, suggesting we should inquire about its date, which was judged just as little cultural and artistic as his recipes, which were in the exclusive format of measures, weights, and cooking times.

Once he entered, in Paris, excusing himself for his dress-coat: he had "dined with a princess". That was probably just true, but he could easily say it: nobody would believe him. My aunt asked ironically: "a princess of the good life?", by sheer luck, as we shall learn later, she was close, albeit at the wrong moment.

When some evening my grandmother would sing, M. Swann got asked to help moving the piano and turn the pages, which he loved to do. Imagine! While an invitation from Twickenham, or others totally above the social reach of my family might sit in his pocket!

That would later all radically change, but at this time, though of course I too knew nothing, he was for me the most marked figure under all people I knew, master of his own time, smelling of those walnuts, those baskets with raspberries and tarragon he often brought us.

"Pourtant un jour ...". Revolution of Swann's status in our family. But not without a blow.

The mask that my family had dressed M. Swan with, so much to his pleasure and amusement, nearly fell when one time my grandmother visited the marquise de Villeparisis, whom she liked a lot, which was mutual, but whom she considered socially above the level suitable for a personal friendship with herself.

The marquise had heard that Swann regularly visited us and said that he was a great friend of her nephews des Laumes. But Grandmother firmly maintained her social positioning of M. Swann, and moved the des Laumes down a bit.

One day Grandfather read in a newspaper about M. Swann's high contacts, including descendants and friends of historical figures that interested him. This, however, was far from the final breakthrough, for my great-aunt despised people seeking company above their own social level. Indeed she once terminated her intercourse with a lawyer's son after he had the temerity to marry some highness. Such lads were, in her eyes, frivolous adventurers to be shunned by decent people like us. She felt her stance vindicated when somewhat later Swann married a lady of questioned morality.

Neither did her two sisters understand Grandfather's curiosity about those details of famous people, so far from their elevated aspirations of beauty and virtue. When such frivolous subjects were raised at table their ears shut so completely that my grandfather, if he needed them again, had to sound his glass with his knife.

But finally the closed system acquired an irreparable tear. That was when, one day before Swann would come for dinner - without wife! -, the Figaro featured a picture of a painting "from the collection of M. Charles Swann".

Some silence persisted after the news had spread our sitting room, after which my grand-mother said: "I have always told you he had taste!". This provoked a fierce reaction of my great-aunt, who, to avoid all doubts, denounced Grandmother's pigheadedness in general, and invited us all to line up behind her.

But she failed: another silence ensued.

Things seemed to go entirely the other way: my grandmother's sisters planned to raise the issue of the Figaro painting at table tomorrow. My great-aunt engaged in a meritorious rear-guard fight by assuming M. Swann extremely embarrassed having himself in a newspaper, that tomorrow he would just experience his first recovery from that blow, and that it was a matter of civil decency and Christian charity not to remind him. In vain. The bear was on the loose.

Nervously, my mother anticipated that my father tomorrow would touch on Swann's wife and issued the unsolicited advice instead to ask about his very beloved daughter, the presumed reason for the inappropriate marriage. My father deemed this absurd and frantically showed himself unwilling to behave "so ridiculously".

Amidst the excitement I was the only one regretting the events of tomorrow night: I would have to dine in advance, my mother would not come to kiss me upstairs, I would get my kiss in the dining room and would have to carry it up, all on my own, and keep it fresh until I had undressed and would lie in my bed.

The next evening Swann's opening of our front garden gate caused the familiar sounding of the little bell and the entire ritual rolled off: who would that be, grandmother why don't you have a look, do not talk softly, it's impolite etc. etc.

But this time my mother went after my grandmother. She wanted to talk with Swann à deux, to let him forget our family's disdain for his marriage by having a small charming talk about his wife an daughter. I ran after her: my time of expulsion was near, so I had to get all I could out of these last minutes. Grandfather followed not far behind me. So, my mother did not stand a chance to realize her intention.

And that's how it went on. My entire family in battle for Swann's attention, wiping each other's subjects off the table.

Grandfather's pregnant questions concerning French historical heavyweights lost from what in his eyes were banalities of Céline and Flora, my grandmother's sisters, to which he ceded with mumbled irony, Swann did not forget him and came back to it at the first opportunity, but then Céline and Flora started to apply the technique of taking keywords from the conversation hostage to totally change the subject and redirect the attention to themselves.

The contrast with the handling of his presence up to the previous dinner must have given Swann some amusement, that, with hindsight, might have been mixed with a slight pity that he would now never more be asked to move the piano and turn the piece's pages, which I had seen him doing with much pleasure.

"Je ne quittais pas ma mère des yeux ...". Passion makes me brave danger. With more success than I could handle.

Suddenly Grandfather looked at my yawning face and judged it was getting too late for me. Should not I go to bed? Dad, never impressed by the high house rules established in the conjunction of my mother and grandmother, agreed. Reluctant I went on my way to Mam for my kiss, but Dad blocked me good-humouredly: "Give your mother a break. Up to bed you!".

A disaster. There I went.

After the cumbersome taking of all steps, ready to sleep, I got caught in a mental dead end street. Despair overtook me and I considered an expedient: I would ask Françoise, the maid, to bring a letter to my mother. But my doubts about whether she would agree to do that were so elaborate that I decided, once grown up and writing La recherche, to deal with them in utter subtlety. My conclusion was that I should tell her my mother had asked for this message.

She saw through it. Stopping short of opening the letter, she left the room with it in demonstrative pity for parents of a child like me.

It was a relief. In my perception, this message out, the contact with my mother had restored already. And she would come as well. Angry, but nevertheless.

M. Swann would, I thought, have laughed about it. Later I learned how well he knew the oppression not to be in and unable to reach the field of pleasure where the object of your love finds herself.

Mama did not come.

Dreadful. No chance I would sleep. No chance.

Suddenly it dawned upon me how to relieve myself of these miserable feelings: I would not even try to sleep, wait till they'd go to bed and then go to her when I would hear her on the stairs. She would be angry but I did not care.

Yes, all pain faded away. Cautiously I opened the window and listened to the voices in the moonlit garden, and the occasional rustle of the walnut tree. My offense would mean expulsion to a boarding school, surely, but I could not care less.

M. Swann left, accompanied by the entire family, I had little doubt that outside my view, at the garden gate, they would form a guard of honour. After he left, conversation about him was unrecognizable as well.

My father proposed to go and sleep, but my mother was totally awake, she said. They entered. I left my room, entered the corridor. There was the shadow of het candle at the walls of the staircase. There she was. I ran towards her.

First it totally surprised her. Then a storm rose on her face. I expected the worst, but Dad came after her. "Save yourself and do not let your father see you here like a fool on the corridor", she hissed. I said again: "Come to say goodnight", hoping Mam would say something like: "Off to your room, quickly, I'm coming!". Too late. There was Dad.

I heard myself whispering: "I am lost!".

But there my father's disdain of established house conventions saved me: "Just go with him", he told my mother.

Mam, slightly rebelliously insisting on the established rules and regulations got, yes, reprehended is the word: "don't you see there's something wrong with the boy, just do it, we're no executioners are we, why don't you sleep with him tonight".

This later made me think that my father generally was not at all, as I thought at the time, stricter than my mother and grandmother, for he was totally ignorant of my daily recurrent bedtime miseries. Mam and Grandma knew all about it, but loved me enough to force themselves into maintaining a regime designed to diminish my nervous sensitivity and strengthen my will.

There I lay, in bed, in tears, my hand in my mother's, who was sitting on a chair next to me. Françoise entered and asked "what makes him cry so much?", and my mother answered; "he does not know himself, just prepare the big bed here and go to sleep." And she stayed with me.

A prize that with good behaviour of whatever kind would have been totally out of reach.

Now my tears for once were accepted as forces beyond my will, their bitterness was not mixed with the usual scruples. I allowed myself to let them flow freely. The whole situation felt like a victory on Françoise, whom I deemed responsible for the failure of my letter-diplomacy, and, of course, on my mother herself.

I felt like a big man, I should have been happy, but I was not. I felt like, like Patroclus on the walls of Troy, I had called disaster over myself, as if I had, by forcing Mama to stay with me this night, had caused her fall from her motherhood of me. I wanted to tell her she could go and sleep at her normal place and please be my mother again, but that would kick up only more dust, I thought realistically.

I looked at Mama's beautiful young face, she now seemed older to me, I saw a grey hair, a little fold, at least in her soul, and cried even harder.

And there something unheard of happened: my crying seemed to contaminate her, who never gave in to tears in my presence. She seemed to swallow a little tear-drop, saw I noticed and said: "Now see what you did, you little goose, now you mother is as foolish as yourself. Come, sleep we can't, let's take a book."

But I had finished all.

"Shall I bring your birthday books?"

I was in for it.

"Will you not regret it when in two days you will get nothing?".

I nodded no. She stood up to get them. They were la Mare au Diable, François le Champi, la Petite Fadette and les Maîtres Sonneurs.

Later I heard that Grandmother first had bought poems of Musset, a Rousseau and Indiana. Fatuous books she deemed bad for a child as sweets but fits of genius not more dangerous than fresh air and a sea breeze. She just had not reckoned with my father who sent her back to buy something else. That turned out to be George Sand, because, she told my mother: "I am really unable to buy something badly written for the boy".

When my grandmother bought something it should have a touch of culture, something intellectual. When she liked to present me a picture of something, she might buy a photograph, but of a painting of the scene, to let it have something artistic. Thus I had wall-photos of the cathedral of Chartres by Corot, the Grandes Eaux of Saint-Cloud by Hubert Robert, and the Vésuvius by Turner.

This taste of hers could bring her in trouble occasionally, like when one time she was asked to buy a chair as a marriage present, and produced something that, though having artistic value, in the house of the newly wed collapsed at the first attempt to sit on it, which caused her, after rest at home had got air of it, to be subjected to merciless interrogation and reproof.

And so Mama sat next to me, in the middle of the night, with François le Champi. Something like this, I knew, would never happen again. Her reading moved me so that I resolved to later, when I would be big, deal with it in La recherche extensively and subtly.

"C'est ainsi que ...". Tea with a memorable piece of cake

Thus my memory of Combray was like Bengal-light: bright where it shone (the terrible path between the garden chairs and my bed), darkness everywhere else. Had you asked me more, I could have told some of it, but I would not remember it on my own initiative.

On a winter day in Paris something remarkable happened. I came home, my mother saw I was cold and offered me a cup of tea, which I never drank. I declined the offer at first but then I thought: "Why not". She gave me a Petit Madeleine with it, such a soft piece of cake. I sucked it in the tea and took a sip.

This had a curious effect. A great happiness came over me, making me forget all little worries of the day. At once I ceased to feel like a mediocre, accidental, mortal being.

Where did that come from? What did it remind me of? For quite some time I tortured my brains, even shutting my ears to prevent any distraction. Frustrated, I attempted to get it out by thinking of totally different things. To no avail.

I took another sip. Something moved a little, deep inside me, but soon it was silent again. It would have sunk back, I thought. At least ten times I tried to get it to the surface, until I reached the point to forget about it and resume my life.

But then it came: aunt Léonie. Sunday morning. Combray.

On Sundays I would not go out before mass. I went to say good morning to her. She sat in her room, soaked a piece of Petit Madeleine in it and gave it to me.

I had seen those Petits Madeleines often enough but that had not triggered memories. Scent and taste did. And it would last quite some more time before I found why that feeling of great happiness got tied to it.

Like in that Japanese game where one throws small, prepared, coloured pieces of paper in a bowl of water, that while getting soaked unfold themselves to reveal flowers, houses, and even recognizable people, all flowers of our Combray garden appeared, and those of M. Swann's park, and the water-lilies of the Vivonne, and the good people of the village, and their small houses, and the church, and entire Combray and the environment, all that has shape and extension, village and gardens, out of my cup of tea.

"Combray de loin, ...". Tante Léonie and Françoise.

My great-aunt, niece of my grandfather, had a daughter, Aunt Léonie, the one of the Petits Madeleines, who had stayed behind at the spot where her husband Octave died, petrified in a state of mourning, devotion and illness. She would never go out again.

I entered on that memorable Sunday morning. In the next room I already heard her talking. To herself. She never did that loudly, for she thought something in her head was weakly fixed and could break loose. But she talked a lot in herself, for it was, she held, good for her throat and would keep her blood circulation going, which in turn, she held, would alleviate the oppressions and tightness of chest she suffered.

Thus one could hear her say things like: "I have to remember I did not sleep at all". She considered her sleeplessness to be the crown on her image, and we played the game with her: Françoise did not "wake her" in the morning, she "entered". When she laid back for her little afternoon nap we said we would retire to leave her to her "reflections". Every now and then her tongue slipped and said she "woke up", or "dreamt". She did sometimes notice it and then blushed.

Françoise was boiling the tea water, and when Aunt was nervous, as now, this Sunday morning, this would be the pharmacy's herb tea. I got the assignment to shake the right amount of the beautiful mix of little stalks and leaves out of the bag on a towel. The tea brew and after that I got that memorable piece of Petit Madeleine.

I should not stay too long, Aunt Léonie held, for that would enervate her too much, and I left the room with the bed on which she always lay, next to the street window to stay in touch with the latest movements in Combray, and the lemonwood sideboard sporting all that gave structure to Aunt's life: the scheme of church services which so unfortunately she was unable to attend, and the daily and weekly medical prescriptions.

Françoise, her maid, loved, when we were there, to devote her attention to us as well. Not only were we the kind of family she loved to work for, she considered it an honorable status to be part of it, in her role of course, but all the more because with us their was attention for her too, above all from my mother, who often talked with her about her daughter and her son in law with whom she did not cope particularly well, and the sadness she still felt about her parents who died some years ago. Françoise had good brains, an enormous energy and she worked like a horse. And she had good looks as well.

When we were there, she loyally kept fulfilling all her obligations to Aunt Léonie, which included aid in the answering of questions left open after a day of gazing out of the window: identity, destination of, or goods carried by, passers-by.

Yes, unknowns in the village. That was something! When accidentally I dropped a remark about an unknown whom my father and me had encountered that day at the old bridge, my father got summoned immediately. He turned out to know him: Prosper, the brother of the gardener of Mme Bouillebœuf. My aunt, embarrassed, excused herself by my mentioning of an unknown en I was urged to mind my words and not create unnecessary havoc.

My aunt was known to have reached an elevated state of excitement after an unknown dog had passed her window. Françoise had been obliged to make a third party enquiry after all dogs that she had claimed to strongly presume had been the one turned out perfectly known by my aunt and in no way satisfying the description.

The tact and agility used by Françoise to keep Aunt manageable without abandoning her role as a maid was of the same high level as her other uncountable services.

After that Petit Madeleine event we went to mass. We had, in Combray a superb little church about which I planned to express myself, later in La Recherche, subtly and at great length, while skipping altogether the sincere sentiments raised in me by all pious words and events during mass. But it should be reported, for reasons that will become clear later, that on the way back we met M. Legrandin, an engineer with some kind of literary reputation. A famous composer even had put some of his verses to music.

He spoke, from under a beautiful blond mustache, very well, even a little too well, my grandmother opined, almost written language. When dealing with fashion and snobbism he would mercilessly chastise the nobility and was not shy to reveal that in his view the Revolution had been half-hearted by not killing them all, to the dismay of my grandmother, for she pitied M. Legrandin's sister who had married in the nobility.

As a visitor, it was very hard to leave Aunt Léonie with the prospect of being invited again. Two rather large groups had to own up at once. First, there were those recommending a good steak and some fresh air. The second was that of those who loyally accepted her professed self-diagnosis of irreversible illness and ongoing corporeal degeneration. Thus remained: A. The curé, hors concours, and B. Mme Eulalie. Mme Eulalie knew how to to it! "It is over with me, Eulalie", Aunt could say it twenty times but Mme Eulalie steadily replied with inimitable firmness: "I know your disease like yourself, madame Octave, but, madame de Sazerin said the same yesterday, you are going to be a hundred!"

"I do not ask to become a hundred", my aunt would reply, for she did not like to commit herself to a number.

Mme Eulalie, former maid of a deceased lady, who made this type of visits as a kind of church volunteer, and in doing so, confessed, at appropriate moments, the restrictions of her small household budget, had established herself in no time to the status of vital element of my aunt's week schedule.

But I actually was dealing with Françoise. Those dishes she served! It seemed never to stop. And we were supposed to finish everything, there she was strict.

After dinner I did sometimes sit on the tiles outside behind the kitchen at the pump. To me it was more a little Venus temple than a kitchen yard. Cool, moist, shady, a salamander next to the impressive heap of fresh vegetable cuttings and the cooing of a pigeon somewhere.

"Autrefois, je ne m'attardais pas ...". Uncle Adolphe vanishes, through me.

Behind the kitchen yard was a cool little room where Uncle Adolphe, brother of my grandfather, used to retire. After a certain incident he never returned.

Discord, through me.

This went as follows: when in Paris, my parents sent me once or twice a month to Uncle Adolphe. Usually he was about to finish his lunch. Then we went to his "study", as he called it. There between all kinds of paintings and ornaments, mostly featuring ladies dressed in transparent veils at most, the valet used to enter and ask what time the horse should be put to the coach. After a ritual moment of contemplation, Uncle would say: a quarter past two. He always said a quarter past two.

It was in that time I started to fall in love with theatre, but entirely platonic, since I was not allowed to go. I read all announcements and made myself a ranking of actors and actresses. With my friends I would not talk about anything else. I would storm a new boy in class and ask whether he went to theatre and what according to him were the best actors and actresses. Then, when necessary, I reshuffled my rankings.

This detail I had to add since my great-uncle, a retired military commander, knew a lot of actresses; and a lot of whores too. The difference between the two was not yet entirely clear to me at the time, but I did sense some unexplainable irony when at home an actress was discussed and my father told my mother: "a friend of your uncle ... ".

I myself only fancied portly gentlemen failing to get access to an actress, while I simply got introduced to her at my uncle's place.

Twice before already, Uncle had almost disappeared from my life. The first time was when he had the courtesy to introduce one of the ladies to my grandmother, the second when he had surprised another one with some of our family's jewelry.

One day approaching his home for a visit, an elegant coach with two horses was waiting. Inside I heard the splashing laugh of a young lady. The valet opened and said, in quite an embarrassed tone, that Uncle was "very busy", but nevertheless went off to announce me, upon which I heard the young lady again: "O, let him come in for a minute, I want to see him! He looks so much like your niece". My uncle's reply was low voice but it had the sound of reluctant agreement.

"He has beautiful eyes, just like his mother", she said once I was in.

My uncle disagreed and pointed at similarities with other family members.

She was very beautiful, but in vain I looked for theatrical traits or testimony of any of the enigmatic objectionable features that my parents had led me to look for.

"Well, it's time to go home", Uncle Adolphe said after a while.

I felt rising in me an urge to kiss the hand of lady, though it seemed to require a daring close to that of an abduction. Suddenly I turned out to have done it already.

"Isn't he sweet! And charming, he is like his uncle too, he is going to be a real gentleman", the last word she pronounced as English as she could.

At goodbye my passion for the girl made me cover my uncle's tobacco cheeks with kisses. Maybe he urged me in covered terms not to report her at home, but I was so full of it that, all excited, at home I told my adventure in every detail. There was nothing wrong from my perspective, but my parents upheld another one, and immediately put themselves in communication with Uncle Adolphe, as I later learned through third parties.

The next time I met Uncle Adolphe on the street, I got overwhelmed by the conflicting feelings of sadness, gratitude and remorse, and wished to share those with him. The massiveness of my emotions made me judge insufficient a simple lifting of my hat, and not touching upon anything better, I ended up looking in another direction. My uncle firmly drew the conclusion I did so under my parents' instruction and in all the many remaining years of his life so full of healthy exercise and well-being we never saw him again.

"Aussi je n'entrais plus ...". Giotto and the amazingly pregnant kitchengirl.

The kitchen aid was more of an institution than a person since we had another one every year.

The year in which there was so much asparagus, with all the peeling work involved, it was a plump clumsy girl in late pregnancy. We were amazed how much work Françoise gave her, because her belly which was already judged to be at maximum size, kept growing and growing. Panting and lifting she walked behind it. In all eyes, but understandably, her services tended to fall well below standard.

She reminded Mr. Swann of a fresco in the Arena of Padua and he often asked: "How is the Charity of Giotto?" In his eyes, the girl had assumed the plump shape of those virgins with their straight cheeks, strong and masculine, as they personify virtues there.

I could not yet appreciate those frescos by Giotto at all, though I planned, once that would have changed, to devote an ample amount, if not an outright overload of subtle words to them in La Recherche, if only to unambiguously prove that later on nobody had to tell me anything of this elevated subject, and that it has, with that kitchen girl, absolutely nothing to do.

"Pendant que la fille ... ". Reading, novels, and - again - memory

I was lying in my cool room in de summer heat of Combray. In my book events passed by as if I held my hand in a little mountain stream.

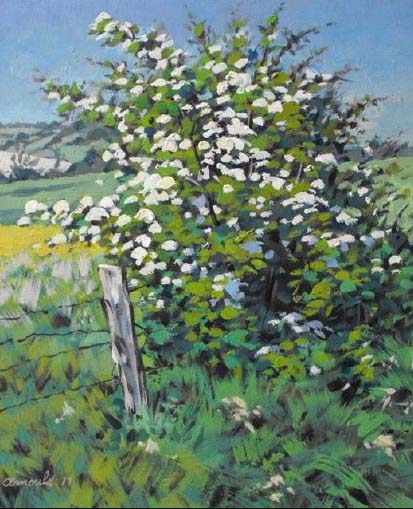

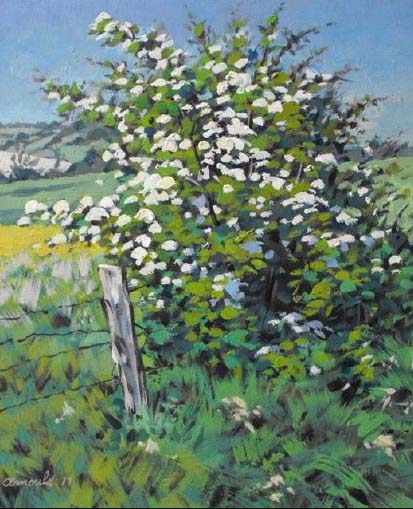

Even when the heat resided only a little bit, like after some drops of rain, Grandmother came to pull me out of the house. I took my book and continued reading in one of those foldable beach chairs under the walnut tree.

Novels were not "real" according to Françoise. But they moved me more than the daily events in Combray. Then how could they be less real? The inventor of the novel had understood that it is the image that matters, that suppressing the underlying real person is a decisive step to perfection. That real person is the inscrutable dead weight a novelist frees the reader of. You deal purely with acts and feelings, which are on their own far more real, since the reader, whose mind is what reproduces them anyway, even in case it concerns a real person, can totally stop doubting now that questionable intermediary has been removed.

This is how a novelist succeeds to guide us, in one single hour, through so much luck and misery as in real life we will not experience in years, since the pace of observations on which we depend in our real lives is far too slow. Changes in our hearts go far too slow to notice and if we dig for them anyway this founders in cumbersome comparisons with our earlier selves and doubts about our own memories. But the novelist easily puts them before us!

Besides my occupation with the events of characters there was, further down, the landscape in which it all happened, and, again further down, the garden in which I was sitting.

This is how to explain the curious fact that I, when remembering Combray, think of a mountainous landscape with cool splashing streams. While the heat at that moment could have been unbearable!

And in my memory of the dreams I so often had of a woman that loved me, she did not walk sweating in the heat, but bent herself over me, to the satisfaction of both of us, in the freshness of the mountains.

While absence of a living person behind a novel's character makes things more real, with landscapes it is different: I really believed that if my parents would have taken me to travel and see the landscapes described, I would have made an invaluable step towards conquering the truth. The landscape stimulates you to surpass the novel and get out of it.

Behind the characters, the novel's landscape, and our garden, there was a fourth layer in my consciousness: realizing how comfortable I was sitting, to smell the air and to know I was not going to be disturbed.

"Quelquefois j'étais tiré de ma lecture ... ". Bergotte and his for my family unbearable postilion, my friend Bloch.

Once I got brutally pulled out of my book by a wild sprint of the little daughter of the gardener. She ran down an orange tree, cut a finger, broke a tooth but kept shouting: "There they come, there they come!".

On such Sunday's all houses' staff would sit outside the street gates to see the walkers pass by. Now they hastily took their chairs to fly to private ground. Dust blew up. The local garrison, on maneuver, horses and all, would use the full width of our street.

"Poor children", Françoise would say. Then the gardener: "How lovely it is to see the fearless youth pass".

But I got more overwhelmingly affected when M. Swann once entered our garden and saw me reading Bergotte. His comment had a stunning effect: the background of violet loosestrife before which the ladies of my dreams invariably used to appear would get replaced by that of a cathedral's portal.

Bergotte was given to me by my friend Bloch, older than me, after he first had eloquently sneered at my admiration for Musset's Nuit d'Octobre, recommending me, in passing, some poems void of content, which amazing property, he held, did far from prevent them being brilliant, which in turn brought me, who wanted in a good poem to find Truth Itself, in some kind of confusion.

Bloch's career as a visitor of my house was an outright disaster. My grandfather noticed with emphasis that always when I took a particular interest in some of my acquaintances, it would be a jew. Of course he could not leave it there, since his own friend, the late M. Swann Sr. with his golden heart, had been one, so he continued to claim that in his judgment, I never chose one among the best in that questionable corner. When one was around he hummed or whistled songs about Jews as well, and I always nervously hoped the visiting friend would not know the words.

When my father once saw Bloch entering in soaked clothes, he asked mockingly: "But master Bloch, how is the weather? The barometer points well, you confuse me", he got retaliated by: "There is no way I could inform you Sir, for I fundamentally live outside all physical contingencies and my senses never take the effort to monitor them".

My father, his ears red, hoped that the boxes on them had escaped my observation and tried to preserve his standing in my direction by sticking to the literal interpretation of this small exchange: "the imbecile does not even know what kind of weather it is!"

When at table my grandmother once confessed she was not feeling very well, Bloch brushed a tear from his eyes, concerning the true intentions of which a family-row arose.

Subsequently, Bloch brushed off everybody by arriving, covered with mud, one and a half hours late for lunch, and instead of excusing himself, made this speech: "Never I allow myself to be influenced by the turbulences of the atmosphere, nor by the conventional partition of time. I would be delighted to reintroduce the opium pipe and the Malayan cris, but I totally neglect that of infinitely more detrimental and outright bourgeois intruments such as there are the watch and the umbrella".

No more need to add: I held Bloch high.

And he kept visiting Combray. My parents restrained their grudges for my sake, though they would surely have preferred me to receive more bourgeois friends. Bloch even sent me a fruit basket after, somewhere far, he had thought of me in a favourable terms, which my parents judged odd indeed.

My mother feared the influence of my conversations with Bloch, she did not know the worst had happened already when Bloch had advocated the value of meaningless poems. But finish and end were reached when he said he could inform me from usually trustworthy sources that my great-aunt had a wild youth during which she had been sponsored from many sides - and, after, I am sorry I have to add, my youthful innocent enthusiasm had inspired me at home to table this.

But what he said about Bergotte was true. No doubt.

"Les premiers jours, comme ... ". from Bergotte to Gilberte (though I would not yet learn her name).

The first days I read Bergotte I was occupied purely with content and still unaware of the style that would later take me away, but soon I halted at phrases like: "touching images that for ever would ennoble the venerable and charming facades of the cathedrals", which to me, expressed an entirely new philosophy by the miraculous images that, as it were, awoke a chant in which harps burst out to accompany the Sublime.

Not much later I even had the "perfect phrase" experience: a phrase melted with phrases in other books that it reminded me of, which gave me a sense of depth and volume, as if I was not reading Bergotte, but The Book (in the abstract), by which my mind seemed to get bigger by some kind of inflation. That was something, I'll tell you. My god!

In that time, there still were only a few admirers of Bergotte: a friend of my mother, and the waiting times for our village doctor's patients seemed to have increased a bit since he too had started reading Bergotte. The first germs of a little flower that can now easily be found in every village all over the world.

I got haunted by the urgent need to have Bergotte's light shining on every subject that ever had occupied me. Of course I resolved to express myself, later, in La recherche, subtly and amply about Bergotte, in order to provide my future dear esteemed readers with something to skip.

That was the stage in which I found myself when, as I said, M. Swann entered our garden and saw me reading Bergotte. On his question I told him it was Bloch who had recommended it to me. M. Swann remembered Bloch well, he said, for he strongly resembled Bellini's Muhammad II, "and anyway, he has taste, for Bergotte is a most charming author". Then, breaking, for once, with his normal discretion, he said: "I know him well, and he is also a great friend of my daughter. They often visit old villages, cathedrals and castles together. Would you like me to ask him to write something in your copy?".

This was too much for me. But I managed to ask my top question: what according to Bergotte, was the best actor? M. Swann did not know, but, as far as actresses was concerned Bergotte was most impressed by la Berma, whom, based on information thus far collected, I had on second place.

"Did you see her?", Swann asked.

"No Sir, my parents do not allow me to go to theatre."

M. Swann regretted that. He praised la Berma and professed not to believe in that "hierarchy" of arts, almost pronouncing the inverted commas, as he also did with key words used by the sisters of my grandmother when discussing a piece of art. It used to annoy me a bit, his way to express his abhorrence to seriously give his opinion. I took it for a way, apparently deemed elegant in his Paris circles, to counter the provincial dogmatism he got snowed under by the ladies.

Something fishy there: he even spoke with dédain about newspapers, stressing the irrelevance of the bal masqué given by the princess of Léon. One had better read books, he said. But did he not devote his own life to the pleasures of those circles? Or did he have another life elsewhere, free of quotation marks?

As far as Bergotte was concerned, M. Swann was not the only one who called him "most charming", "someone who expresses himself a bit affected but agreeable". I never heard anyone say that Bergotte was a "great author".

At the time I had no clue yet about social hierarchy, so, surely after I learned Bergotte was his frequent guest, I took our apparent impossibility to visit M. Swann and his wife as a sign of M. Swann's prestige, enhanced by what I was told about Mme Swann: she painted her hair and used lipstick.

Now I fancied how his daughter, against the background of a noble cathedral's facade, would lovingly introduce me to Bergotte.

"Tandis que je lisais au jardin ... ". The life of Aunt Léonie, part seven (or eight?).

While I was reading in the garden, which, according to my great-aunt was odd on weekdays, since, she held, the prohibition of doing useful work only applied to sundays - she never sewed on sundays - Aunt Léonie chatted with Françoise, waiting for Mme Eulalie. Aunt said she had seen Mme Goupil pass without an umbrella, which, she predicted, given the dark sky, would earn her a wet dress

Françoise agreed, at least to the possibility.

"O dear!", Aunt said, putting her hand at her temple, "now I told myself to ask whether she reached church in time for the elevation, I should not forget to ask Mme Eulalie".

There was a slight panic when the church clock struck three: Aunt had forgotten to take her pepsine. She took it and quickly snatched the bible from the table to read passages prescribed for the hour. "Three o'clock! How time flies!"

And yes, it started raining. Aunt heard the little bell of the garden gate and sent Françoise for reconnoitering. It was Grandmother. "Oh, always the same", Aunt said, her eyes directed to heaven in demonstrative despair. Françoise knew that Grandmother should be piqued somehow but wisely kept that for herself.

"I think we should forget about Mme Eulalie today", Aunt sadly said.

"It's still long till five", Françoise said, "it is only half past four".

And yes, there she came. But shortly after she entered, the curé appeared at the door.

Well, the curé always was a welcome distraction, but not, of course, when Mme Eulalie was visiting. Quickly she asked Mme Eulalie to stay a bit after the curé would have left, something Mme Eulalie surely would have understood without asking.

The stream of words of M. le Curé took off. His flux de bouche always reached cruising speed when he embarked on the subjects of his church, history and etymology, and he never lost much time to get there. Then, all his company could do was wait with attentive mimic.

After the curé had finished and left. my aunt was so exhausted by her failed attempts to remember the names and concepts that had passed that she was forced, after handing over the usual coin, to send Mme Eulalie away.

The little transaction always took place out of Françoise's sight, whom it of course did not escape. Françoise considered herself to be part, albeit in her role, of our family, and thus quite distinguished in her own ranks where she liked to be addressed as "madame Françoise". She held her wage, with which she was totally satisfied, using not her own, but the our family's budget as the standard, as a trifle. But she had different ideas, since she never succeeded in determining the exact quantity of that little transaction, about what was so frequently given to Mme Eulalie, someone, let us face it, ranking well below her.

In Françoise's estimate, Mme Eulalie would soon be able to buy an entire farm. She did not want all that money herself, but, as said, in her status of a bit of a family member, she judged these gifts to Mme Eulalie irresponsible and unnecessary expenses for "us all". Though of course Aunt Léonie was responsible, and Françoise thought she should make very sure her mixed feelings would not transpire to Mme Eulalie, Françoise cherished some Bible passages where God's displeasure with people "like Mme Eulalie", in her judgment, showed.

Françoise had left my fatigued aunt only a few seconds when she got recalled by four firm hits on the room bell. "Has Mme Eulalie gone away already? My God! I forgot to ask her whether Mme Goupil has reached mass before the elevation!"

But Mme Eulalie had left already.

Thus Aunt Léonie passed her days in what she herself tenderly called her "petit traintrain".

I remember one time that year that this "petit traintrain" got challenged. Our overly pregnant kitchen aid got, unexpectedly unexpected, her contractions. Françoise had to collect the midwife before dawn, while Aunt, as a result of the screaming of the girl, was unable to engage in her "reflections". I got sent to scout and ask Aunt whether she needed anything.

She was lying with her back to the door I opened and snored a little. I judged this observation sufficient for my report to my mother. Some noise on my retreat shortly interrupted the snoring. It returned, to settle at slightly lower pitch. Then she woke up, turned on her back, revealing the side of her face to me, which expressed a fear. "Thank God", she murmured, "We only have the hassle of that girl giving birth ... I dreamt my poor Octave had resurrected and wanted me to take a walk every day". Her arm made an unconvincing attempt to reach her rosary on the bed table. Then, in total relaxation, she fell asleep again.

"Quand je dis qu'en dehors...". Saturday (for insiders).

On Saturday Françoise would go to the market in Roussainville-le-Pin. To be able to leave on time, on Saturdays, lunch would be an hour earlier. Since this looks like an insignificant issue I cannot escape explaining how this was a cornerstone of our family culture in Combray.

To start with Aunt Léonie: the routine had so deeply sunk into her that she would have been brought in total disarray when one Saturday she would be told lunch would be at normal time.

To the others it was what distinguished insiders from outsiders. Of many small intentions and plans for the day the small aberrance would be explained in passing by a simple: "for its Saturday, remember", and after a Saturday lunch, even the sun would need one more hour to reach its zenith.

The month of May would outdo the normal "Saturday" ritual, for after dinner we would go to church for the "mois de Marie", in my memory inextricably linked to the Vinteuils and the hawthorn.

"Comme nous y rencontrions parfois M. Vinteuil ... ". The Vinteuils.

M. Vinteuil often referred, full of indignation, to the "neglected youth in this epoch's world of ideas", which had trained my mother, when she expected to meet him, like during the church visits of the mois de Mai, to perform some extra checks for foreign matter on my clothing.

M. Vinteuil, now a widower, had been the piano teacher of the sisters of my grandmother in Paris. After he received a substantial heritage he had moved to nearby Méséglise and was considered fit to occasionally be received in our house, which however had taken an end by consequence of M. Vinteuil's fear to meet M. Swann after the latter had concluded his "improper marriage in the spirit of the time".

We kept visiting M. Vinteuil. My mother once asked him to play one of his piano compositions. He was delighted but haunted by a massive fear to ask too much attention. When once, visiting M. Vinteuil, I left my parents even before reaching the house, to play on the steep slopes around it, I saw M. Vinteuil hastily push the piano in a corner.

The only passion of the widower was his little daughter, a bony, robust girl with freckles that he treated like a fragile angel by throwing shawls over her at the first whiff of wind.

Leaving church, kneeling before the altar, I smelled the hawthorn put there and its little leaves started to look like the freckled cheeks of the little daughter of M. Vinteuil.

After church, when daytime, a long family walk would follow, under my father's leadership, for the rest would err immediately. When we were tired and had enough of it, my father would ask: "where are we?" and we would have no idea.

Then Dad would point out our garden gate, my mother filled with admiration.

"Si la journée du samedi, qui ... ". Aunt Léonie embarks on intelligence operations.

When Aunt Léonie's weak and maniacal body was for a while not affected by disturbing events, she could build up some taste for disaster.

Then, during a game of solitary she could get haunted by a phantasy in which our entire house burnt to the ground with no survivors, and she would collect all forces in her terminally ill body to organize - the entire village flabbergasted - our complete funeral in appropriate mourning, for she really loved us, after which she would, to recover from the blow, spend the summer on her lovely farm the Mirougrain, were there was a cascade.

After this stable routine of her "petit traintrain" had continued undisturbed even longer, she got dissatisfied with mere fantasy and started to suspect Françoise of stealing.

Similarly to many card games in which she was used to play both sides, she started to create dialogues in which Françoise, deeply ashamed, excused herself and she, Aunt, answered with such a fire of indignation that once we found her bathing in sweat with scintillating eyes, her false hair displaced to lay bare her heated forehead.

But that got boring to her as well and she informed Mme Eulalie behind locked doors that Françoise had come under suspicion and was about to be sent off. Françoise, likewise, was informed about strong suspicions of disloyalty from the side of Mme Eulalie, who was, on short notice, to be denied access to the house.

Aunt's intelligence operations were conducted entirely from her bed, she did not risk a cold by embarking, say, on a full kitchen check, so she concentrated entirely on purported inconsistencies in Françoise's words an body language until in her eyes she had enough proof to confront her. Françoise was quite taken aback. For Aunt, who enjoyed it, this only added to the overwhelming incriminating material.

My mother feared that Françoise would not be able to cope with this for long, and would now really start hating Aunt Léonie, whose raving reached new levels every day. But Françoise's understanding and clemency enabled her to swiftly accommodate her management style under the stunning adoption of her role as Aunt Léonie's stealing maid.

" - 'Je veux profiter, dit-il ... ". About Legrandin, with, by way of intermezzo, another digression concerning Françoise's attitude towards the lower classes.

"I fear we are no longer on speaking terms with M. Legrandin", my father said, "he ceased greeting me. A real pity, such a nice man".

M. Legrandin had passed in the company of a chatelaine of a nearby castle, not in our circles. I had witnessed the incident, both the event and Father's bewilderment afterwards, so, as always, keen to know Françoise's dinner menu, did not wait to hear father's story.

It should have been imagination, or M. Legrandin would have been accidentally distracted, was the general family judgment, vindicated at te next encounter when M. Legrandin greeted us cordially. He quoted Desjardin: "the forests dark already but yet the sky is blue", lit a cigarette, gazing at the horizon in silent contemplation, which he interrupted after some moments to continue his way with a somewhat overly cordial "goodbye comrades".

But we aren't there yet, I was on my way to the kitchen while my family discussed my father's somber hypothesis.

Françoise had everything going and walked, as a slave-driver of Nature, between the steaming pots.

Poor Charity of Giotto sat at the kitchen table and, looking like she was carrying all misery of the world on her own, peeled an impressive heap of asparagus, while Françoise turned the chicken as only she could, until, all Combray knew, not even a blind man could doubt it: this was chicken of Françoise.

Because the plump kitchen aid had just given birth, she could not walk and Françoise was behind schedule, while another chicken had to be slaughtered. Stress. Quickly she went out to grab the loudly resisting poultry and made some attempts to deal the fatal blow, which, however, failed. "Rotten beast!" she swore. The next blow did the job. She allowed the blood to run away, but it did not cool her temper. "Rotten beast", she mumbled again reentering the kitchen after having turned her back to the remaining convulsions of the unfortunate fauna.

I fled, wishing that Françoise would be banned from our premises at once and forever, but on the stairs I had already discovered the wisdom to better judge Françoise on the end result of her endeavours. After all, Françoise's life had, I told myself, a front view, the neatly arranged dinner table where we folded our hands several times a day, and a rear view with the screaming and the squirting blood, as I knew also to be customary under the regime of many a king and queen.

Françoise considered the suffering of the Charity of Giotto, who had a hard time after giving birth as theatre. But she could be quite compassionate as well, as illustrated by the memory I will now relate.

Our doctor had put a bookmark in one of our medical books where we could read the symptoms indicating that her problem, some kind of infection, got more serious and would require attention.

My mother woke up one night by the screaming of the girl and asked Françoise to get that book from the library. When after an hour Françoise had not returned I was sent for her, and found her in the library, reading the book, in tears. At every symptom that she passed her crying reached a new peak: "O Holy Virgin, how can it be God's will to let an unfortunate human creature suffer like this. O, o, poor girl!".

But once I had pulled her with me to the victim her compassion vanished totally leaving her exclusively with the irritation about the hassle it caused her.

And when she thought she was out of reach of our ears she said: "She did this to herself. O, how can the good God have so totally abandoned a boy to let him start with her, my mother always said: 'Who starts fancying the rear of a dog thinks it's a rose' "

When Françoise's grandson had caught a cold she walked seven kilometers at night but the next morning our breakfast would be perfectly ready for us and on time. We never encountered staff helping her in our house. She shielded us hermetically. Even when very ill, she would always come herself. Always. Later I have concluded that we ate so much asparagus that year because poor Charity had such a heavy allergy for them that in the end she was forced to resign.

This, needless to say, explains way we changed kitchen staff so often.

After we saw M. Legrandin at the end of mass, outside the church with the husband of the chatelaine with whom we had seen him some weeks earlier, introducing him, shining with delight, to another great landowner of our region, we knew that we had to fundamentally revise our opinion, since while we passed M. Legrandin, his gaze firmly locked to the horizon.

We had forgotten our church donation and Mama sent Papa and me back to bring it. Thus we met Legrandin again, this time with the noble lady on their way to her coach. While he continued his graceful conversation with the lady he seemed to give us a minuscule sign from the outer edge of the eye widest from her.

The previous evening he had asked my parents to send me to him for dinner today. "Come and remind your old friend", he had said, "of how he was when he had your age", which he elaborated upon as usual: in phrases that, if literally written down could have been sent to a publisher right away. After this second church incident the question arose whether I should go, but there was judged to be insufficient evidence for a measure by which we would put our own cards so blatantly on the table.

So I had a diner à deux on M. Legrandin's terrace. As a reading child I understood without effort the elegant, often long sentences with which he dealt with himself and the fair moonlight. And now I had seen him so close with the aristocracy, I found the courage to ask him whether he knew the chatelaines de Guermantes, giving myself the pleasure to let a dream make its first step into the world, by at least talking about it.

M. Legrandin said he did not. But he did so in a way to which I decided to devote later, in La recherche, ample and subtle attention. In short: he made it seem like his lack of connection with the chatelaines de Guermantes surprised himself too, but at the same time that he always had managed to maintain this very distance, for sophisticated reasons, with severity and cunning.

Subsequently, he posed again eloquently as we knew him: an ultra-Jacobin, contra the nobility up to denying its right to exist. I did not completely grasp all points he made there, but after having seen him this morning, in the company of those noble gentlemen and refuse to greet us bourgeois, I was sure there was something fishy here.

And I knew the name: M. Legrandin was a snob. A snob who refused to see himself as such. In indulging in intercourse with personalities of the noble class he wanted to believe to have yielded to forgivable passions for beauty, virtue, and things like that.

Surprised by my question he had first slipped on the wrong role, and then could only retouch what he had already applied.

"Maintenant, à la maison, on n'avait plus aucune illusion sur M. Legrandin ... ". M. Legrandin and the heavenly geography of the Basse Normandie.

Now we knew that we should have no more illusions about M. Legrandin and his invitations got scaled down.

My mother had to laugh a bit about him, but my father was unable to produce the disdain such required, and even opined, when I was about to go to the Balbec sea side with my grandmother, that we should ask M. Legrandin to link us to his sister who lived near there, married into the nobility.

Grandmother thought it nonsense: we would be at sea and there should be nothing to distract us from the associated healthy activities.

Before this issue was resolved at home, M. Legrandin worked himself in a trap: we met him at the banks of the Yvonne and his immaculate prose touched Balbec.

Mij father did not let the opportunity escape and went for a surprise attack: "Ah, you know people there! The little one is going there with his grandmother for two months".

M. Legrandin had, until that moment, looked at my father and apparently he thought it best to keep doing it, his eyes a bit larger, until he looked like gazing right through him, which suggested something like: "how dare you".

My father, very irritated, asked again: "Do you have friends there, you told us you know Balbec so well!"

M. Legrandin decided to confess that, to be honest, he had friends everywhere, and kept shielding himself from the ever fiercer attacks by my father until the latter started fearing if he would insist, the most he would get out of this would be an entire ethics of the landscape and the heavenly geography of the Basse Normandie, and surely never a letter of introduction to M. Legrandin's sister, married into the nobility.

And this hermetic entrenchment was inspired by irrational fear, for the chance Grandmother would use the letter was totally negligible; if M. Legrandin could have weighed the risks in mental equilibrium, he surely would have concluded that on balance he'd far better write the letter of introduction - how embarrassing it might have been for his segmented soul - ready for oblivion.

"Nous rentrions toujours de bonne heure ... ". Gilberte and the dichotomy of du côté de Méséglise and du côté de Guermantes.

For our walks in Combray there were two directions. First, there was du côté de Guermantes, a long walk which had an element of achievement. When we went that way, we should report this to Aunt Léonie, for we would return late for our usual before-dinner visit to her, which would put her on thorns and, after a stroke on her room-bell, Françoise.

The other direction was called du côté de Méséglise or, also, du côté de chez Swann. When opting for that direction we made, since the inappropriate marriage of M. Swann, a small detour to not conspicuously pass the park of his house (called "Tansonville").

I found this out when once it was known to us that M. Swann was in Paris, and mother and daughter absent, for then my grandfather said to my father: "why don't we pass the park, nobody is home and it is a nice shortcut".

Moreover, this turned out to be a nice occasion to have a look at the park and allow my grandfather to tell how it looked like in the times of the old M. Swann, and what M. Swann Jr. had changed.

I felt relieved that we would not come in sight of Mlle Swann, his little daughter, since she, who visited cathedrals with Bergotte, would no doubt look down upon me. But a little later I fancied again that by a miracle we would meet her with her father without an opportunity to hide ourselves, so we would be forced to allow Swann to introduced us to her.

We continued our walk du côté de Méséglise through opulent nature and reached a long hedge through which here and there you could see a park. There I froze: I suddenly stood eye in eye with a girl with reddish blond hair and a face full of freckles. She seemed just to return from somewhere. With a garden spade. Her black eyes shone markedly, may be because she was blonde for the rest, and looked at me sharply. It seized me.

I looked at her, first without expressing anything, in an obsessed absorption of the image, after which for a moment I did not dare to look out of fear Dad and Granddad would see the girl and order me to proceed.

Just before that, she had looked at them both and apparently judged us ridiculous, for she had turned half to hide her face.

Dad and Granddad did not see her and passed me. She aimed her black blinking eyes on me again, with a feigned smile, like she was watching a weird tree. I felt to be the object of insulting disdain. As if this was not enough, she made an indecent gesture that in my pocket dictionary of civil politeness pointed at absolutely insolent intentions.

"Come on Gilberte, what are you doing there!", a shrill voice of a lady in white who had escaped me thus far. A gentleman in denim looked at me intrusively.

The girl obeyed in a docile, unfathomable and sneaky way.

While walking on, my grandfather mumbled: "Poor Swann, this role they let him play. They let him go to Paris so she can be alone with her Charlus, for that's him, I've recognized him! And the little one entangled in this scandal".

Her obedience to the command of het mother, who I inferred was Mme Swann herself, diminished Mlle Swann's air of superiority, which relieved me by reducing my love a bit. But not much later my humiliated heart wanted again to rise or sink, I did not care, to her level. I profoundly regretted I had been unable to insult or hurt her, in order to make a lasting impression. I wanted to go back and shout: "How ugly and grotesque you are, simply disgusting!!"

And thus Gilberte established herself in me. Forever.

"'Léonie, dit mon grand-père en rentrant ... ". Tansonville becomes my sacred place. And again Aunt Léonie.

After returning from our reported walk du côté de Méséglise, Grandfather told Aunt: "Léonie, I wish you had joined us today. You would not have recognized Tansonville. Had I dared, I would have taken for you a branch of those thorny shrubs you like so much".

"Yes", Aunt Léonie answered, "when once the weather is good, I will let myself drive to the entrance of the park"

I solumnly swear she said it.

But the plan alone had depleted her forces.

Thus it started to happen that Aunt would resolutely dress herself when the weather was good and would even reach the adjacent room. Then, exhausted, she turned and fell back on her bed. This was the start of the familiar phenomenon of rising resistance against the stage when old age starts to prepare for death, and which will end up in one ceasing to take the trouble to contact one's most intimate friends.

And curiously enough, to Aunt Léonie, such resignation was made easier by her refusal since long to practice her body and her choice to permanently lie on her bed: the giving up, after standing up, of planned action gave her, once back on her bed, a sweet complacency.

Since I'd seen Gilberte I was eager to bring conversations - inconspicuously - on Tansonville and the Swann family, which had assumed, in my mind, a god-like status. Aunt Léonie's "plan" was suitable for this. "Would she go?", I asked. But after having asked this a suspicious amount of times, I concocted other questions in the answer of which M. Swann of Tansonville would, I hoped, figure.

Here I restrained myself for I knew how we thought about M. Swann's wife and daughter. Often I was nervous for I feared my parents for long understood my feelings and forgave me, what gave me the feeling I had overcome and lost them already myself.

When at the end of the season we prepared to go back to Paris, my mother found me in my best clothes on the path to Tansonville, saying farewell to the hawthorn - in tears.

"C'est du côté de Méséglise, à Montjouvain ... ". The vertiginous fall of M. Vinteuil's self-image.

Du côté de Méséglise, on a hilly plot at a pond, was also Montjouvain, the house of the widower M. Vinteuil, the pianist, as told, of such firm morality that after M. Swann's inappropriate marriage, he ceased to visit us for fear of meeting him. There in Montjouvain he lived, with his plump and bony daughter.

Her horse used to pull a portly two-wheeler, and after a certain time she drove it in the company of a somewhat older friend who had a bad name for she was told to cool her lusts with persons of - for a lady, for the purpose - inappropriate gender.

Not much later she even lived in Montjouvain. M. Vinteuil meanwhile got quoted, mockingly, as admiring the unfortunately uncultivated musical talents of the lady. Usually such quotes frivolously stressed the word "musical". Who knows, may be he even thought so, for the goodness and self-sacrifice of someone in corporeal love can easily reach as far as the relatives of the object.

But no doubt: M. Vinteuil suffered. He avoided his acquaintances, after some months he already clearly started looking older, he spent entire days sitting at his wife's grave. Those who saw him dying of sadness strongly suspected he realized what was going on, but anyhow, he did not interfere. His love for his daughter apparently made it totally impossible for him to cause her grief. But from the perspective of the world he knew she had sunk. Deep. And he had gone down with her.

Once, with M. Swann, we encountered M. Vinteuil on the rue de Combray so unexpectedly that he impossibly could avoid greeting us.

It was far from M. Swann, who liked to see himself as endowed with a charity unhampered by bourgeois limitations, to stiffly exchange some words and walk on. It even pleased him to converse extensively and cordially with a man in the gutters, ignored by everybody. It pleased him even more than it did Mr. Vinteuil and this ended in an invitation to M. Vinteuil to send his daughter to play at Tansonville!

Such a proposal, which would have roused M. Vinteuil's indignation only some months ago, now got received as so endearing, dignified and invaluable that it seemed M. Vinteuil that if kept platonic he would enjoy this invitation even longer and seriously considered purely for conservation purposes not to take it up.

"Comme la promenade du côté de Méséglise ... " Bad weather in Combray, Aunt Léonie's heavening, walking in autumn.

As for walking, du côté de Méséglise was our bad weather option as well. It was shorter and one could walk along the edge of the wood, to enter it when it would start raining. Another shelter was the portal of the Saint-André-des-Champs.

When the weather was even worse we stayed at home and I read. The dripping trees, the landscape, grey as a sea with houses as wet ships, could not spoil my mood, for it was summer and the rain would only make things greener.

Later, I would go out alone on such days, du côté de Méséglise of course. That started after that autumn when we had to return to execute Aunt Léonie's heritage. Finally she'd gone heavening, triggering a last discussion about her in the village between those who had always said that her self-chosen life on bed would destroy her, and those who had maintained, and now felt vindicated, she really had some kind of illness. Meanwhile my parents sat at table with papers and the lawyer, and talked to the farmers.

Aunt's fatal disease had needed fifteen days, during which Françoise did not undress for sleep neither left Aunt's bed side, strictly keeping staff away, not distancing herself a millimeter from Aunt until she had been buried, totally defying Mama's fear that Aunt's manic theft suspicions had eroded Françoise's sense of duty and dedication.

In Françoise's eyes it were even we who had sunk a little for we had not organized a huge burial meal, we had not started to talk about Aunt on a solemn tone, and I even occasionally sang. And on my solitary walks du côté de Méséglise I wore to Françoise's dismay no black but a colourful Scottish plaid.

I got older a bit and did this to pester her. Strange: in books I would have appreciated ceremonial mourning but within short range of Françoise I would resume maintaining that I only regretted Aunt's death, despite her utter ridiculousness, because she had been a good person, and not because she was my aunt.

When Françoise, despite not being used to abstract discussions, took the trouble to expound her view on the special meaning of kinship, I just started to make sick jokes about the pronunciation errors she had made in her explanation.

"C'est peut-être d'une impression ressentie ... ". M. Vinteuil spat on posthumously.

Du côté de Méséglise, at Montjouvain to be specific, the house of the Vinteuils, I also found the first building stones for my understanding of sadism.

I was hot, my parents were busy, I could go and was free to decide when to return.

This made me go to the pond of Montjouvain, which so nicely reflected the roof of the house. There, on the slope, I fell asleep between the shrubs.

I woke up only at sunset, wanted to head home immediately but could not move for fear to cause twigs to crack: Mlle Vinteuil was sitting in her room and I was embarrassingly close, she could start thinking all kinds of things.

I felt sure it was her, though since I last saw her she had become a young lady and wore a mourning-dress. Her father recently died. We had not visited her, for in my mother one virtue was more powerful than goodness: shame.

But Mama pitied M. Vinteuil and she was full of compassion with the extraordinary feeling Mlle Vinteuil should now have to be virtually the cause of M. Vinteuil's death. "Poor M. Vinteuil", she would say, "might he still get his reward some way in heaven?"

Frozen, I waited for a moment to sneak out. Mlle Vinteuil's buggy arrived, she heard it, brusquely rose, took a photo portrait of her father, fell back on the canapé, drew a low table near and put the portrait on it.

When her friend entered she had lied down at one side of the sofa, her hands behind her head in a pose suggesting total relaxation. But somehow this seemed her too inviting in case her friend would prefer to sit on a chair and she stretched, quasi yawning. Though she had a kind of rough dominant attitude towards her friend I thus saw some tendency to have scruples that she might have inherited from her father.

Then, she feigned to lack the energy to close the window blind.

"Let us leave them open", her friend said, "I am hot".

"But it is annoying, they can see us", Mlle Vinteuil said. That did not sound serious at all, she seemed to be provoking some specific answer. Clearly, a game had begun.

"O yes, how annoying", her friend said, "especially here in the countryside on this busy hour ... and what?". She thought she should have a vicious glance at Mlle Vinteuil behind which I sensed some tenderness. "If they see us, the better".

Mlle Vinteuil trembled a bit and rose, craving for words appropriate to the image of the bad girl she wanted to pose for, but she did not know better than to copy something, I suspected, she had heard her friend saying some time: "Madame, it seems, is tonight under the spell of horny thoughts".

In the opening of her crêpe corsage Mlle Vinteuil sensed a little kiss from her friend. A little scream escaped her, she escaped, after which I witnessed a playful hunt, during which the ladies, due the the long, streaming sleeves of their mourning-dresses looked like displaying cranes.

Mlle Vinteuil ended back on the sofa, now with her friend on top of her, so with her back to the portrait so carefully positioned.

Hence, Mlle Vinteuil needed an expedient. "O dear, my father's portrait looks at us, I so often said that it's not its place". Now this was sarcasm of some quality since M. Vinteuil often used this phrase about a piece by himself that he carefully had put on the piano, waiting for notice by third parties, and the ensuing opportunity to get awfully modest about it.

Now the game turned out a ritual, clearly in use for some time. "Why don't you leave it", Mlle Vinteuil's friend said, "can he still bore you, or nag, or throw shawls over you because of the open window? The disgusting monkey!"

"O, be careful!", on a tone of sweet reproach Mlle Vinteuil gaudily masked the excitement her friend caused her with het brutalities. But then she surrendered to it totally, jumped on her friends knees as if on her mother to commonly enjoy the cruelty with which they robbed the poor defenseless deceased from his paternity.