PHiLES home

PHiLES home| Lingeblog Home |

| Previous |

| Next |

PHiLES home PHiLES home |

Crtd 2014-04-07 Lastedit 16-01-20

A phone booth in the blossom

Today I decided to take a look in a curious asset of the village Beesd, a mile from my Linge river mooring. It is a phone booth. Probably all other phone booths are scrapped in the Netherlands. And you can't call in the Beesd phone booth. A teacher bought it to put it in front of his house and make it an exchange library for villagers.

Surely the books there would largely be local Dutch literary folklore, virtually unknown at any distance greater than 300 miles from this booth. Which is, given its quality, a blessing to everyone outside that narrow area, except for the 17th century ship's journal (Amsterdam, Indonesia, China) by Willem Bontekoe. It's English translation is only sold hard copy for a collector's item fortune, so I plan a free translation one time. Bontekoe is not a literary artist, he is a captain writing the journal he is ordered to by his bosses, got it embellished by a reader who sent it to a street-corner printer, thus launching a multi-century resounding Dutch best seller. But what else to write for that spooky public of Calvinist fundamentalists and trustworthy cheating merchants, neither of which like to be seen with a smile on their face, let alone while thinking of themselves? You can write to them about how to navigate the seas, how to organize double bookkeeping, how to build the best military defenses of Europe, human body parts and their functions, animals and plants in the world, physics, microscopic life forms, but providing art literature digestible to them means subjecting yourself to the canons of boredom. Even the Dutch heresies that cost lives and led to book burnings are boring to outsiders. And though the Dutch did some tough self-liberation the artistic predicament lingers on today, surely in literature.

Once in the phone booth I seem to have been saved for the worst. Do I face a selected display?

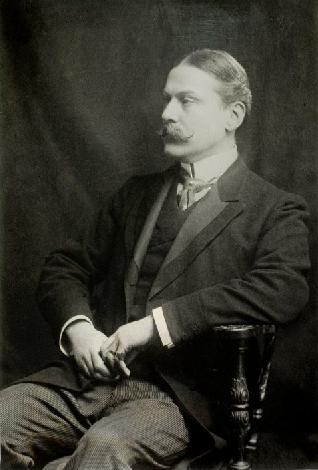

Jozua Marius van der Poorten Schwarz, alias Maarten Maartens, 1858-1915

And a curiosum: God's Fool (Londen, 1893) by a Dutchman named Maarten Maartens, but registered Jozua (Joost) Marius van der Poorten Schwarz. From his sixth till his twelfth he lived with his family in London and decided to write in English. During decades around 1900 he was a famous author in the UK and the US, sold as Dutch writers can only dream of, had great people of the time among his friends. It may be a surprise that I, who read most of my day during over 40 years now, had never heard of him. Ok. Sorry. I am Dutch. The few in Holland who knew about him at the time felt insulted by his satirical style writing about Dutch life, or jealous, or both.

This I gathered in the phone book, a Dutch translation (of 1975, had the anger finally ceased?) in an epilogue by some Dutch professor. And later Google sharpened those outlines by sporting the English "Maarten Maartens" wiki page on top and the Dutch one, though existing, not even on the first screen.

But I am still in the booth. An earlier reader of this copy staunchly ploughed the pages putting some pencil marks at loci involving things like God, Love, Past, Future and Judgement. And, like I am used to do, kept track of them by having their page numbers listed in the back with a keyword. This makes for a bond, I leaf on, though slightly unsettled by his selections. But I encounter a number of neat accomplishment on short distance, like:

"There was a big dinner-party at the Lossells'. Now, what more cheerful than a dinner-party? Especially for those who, sitting comfortably established by their own fireside, with a book and a valid excuse, remember that, but for such valid excuse, they too must have been there."

No it should not be really bad, I concluded, took it under my arm, and reshuffled the books to close the gap. I never leave a mess when avoidable.

Was there more?

I spot a title "Brazilian Letters", by August Willemsen, clearly a virile Dutch journalist who looks at me from his back cover photo as a man who rarely has to pull off his underwear in person.

The first edition is 1985, the youthful beauties on the front should be in their 50's, so grandmothers by now - this is Brazil. But that's forgotten as soon as I see the deeply cut out dancing slips, and, moreover that this is a reprint from 2000. So even at the time the girls were 30, the editor's consortium of "Single Pockets" still judged the rage for them on the Dutch market well alive. Moreover, it is thinner and smaller than Maarten's book so I can slide it under and quickly bring my booty in the car.

My moral impeccability inspires me to replacement - and do not ask why I had it lying ready in my car. First, a piece of my own unsold self-written crap. My mother already moved the largest part from her loft to the municipal refuse dump, but my granted prayer to keep a small stack brought the obligation to dispose, to which she regularly reminds me. Second, Part I of a decisively wretched two-volume book by the French historian Braudel about the Mediterranean in the Spanish Golden Age, the second volume of which I was so fortunate to not yet have ordered.

I do think nobody has noticed my visit to that phone booth

Maarten's novel moves around in "Koopstad" ("Buying Town"), half an hour from Amsterdam by train, slow at the time, click Google Maps and pick your choice, I opt for Haarlem. We sense the air of Dutch mercantile culture. Life is a bookkeeping. The profitable and the good should amount to the same though unfortunately a slight account difference sometimes appears. We keep those as small as possible even in the choice of our marriage partner. Though we are unable to close the cracks completely, we regularly do see somebody freezing, for the sake of good name, in business before all, at the sight of passing vast bulks of money to be grabbed had it not been for scruples. Or the other way around. Or, the worst: loosing on evil action. That must surely be God's work, society observers will never get tired to tell each other.

Maarten's mental distance to Dutch patrician culture, large as it is, shows in its details the daily intimacy he must have suffered, with his pencil on standby. About trade agreements, revenue and heritage law, unliftable cornerstones and stumbling blocs of the novel, unavoidably ending in murder, he speaks as an initiate. His own marriage with a rich party, allowing him to swiftly put down his young talented man's assistant professorship at one of those ghastly Dutch universities, will have further enhanced that intimacy.

Thus Maarten became a man of a fortune further growing by the impressive sales of his books. He could lead two lives: one of Dutch decency and his Anglo-Saxon life at a satirical distance of the first. But here too some cracks seem sometimes to have occurred: He writes: "For in all of us the disagreeable largely predominates over the agreeable side. I know it does in me, because I have frequently been assured of the fact. And if you are not as certain of the matter in your case, that merely proves, not that you are more agreeable than I am, but that my friends are more disagreeable than yours." And the preface of The Greater Glory (1894), transpires that meanwhile more often, and irritatingly, cheerful Dutch dinners went lost to Maarten: "Holland is a small country, and it is difficult to step out in it without treading on somebody's toes. I therefore wish to declare, once for all, and most emphatically, that my books contain no allusions, covert or overt, to any real persons, living or dead. I am aware that great masters of fiction have thought fit to work from models; that method must therefore possess its advantages: it is not mine". But that is not the way to shake off the insulted: even Dutch readers, surely Dutch readers of good English literature know it is totally impossible to shape some novel's character without models. A cook may endeavour to make his dish using very many different ingredients so as to become unidentifiable by their mix, but he can't do without any at all.

Elias, God's own fool, gets born totally normal. His patrician mother is heir to a top fortune, his father is a modest but clever merchant with beautiful eyes. We run a tea trade. Mom dies soon, leaving his father with son and fortune. His second marriage is less successful in all respects but yields twin brothers. The heavy testator had determined that his fortune would go to his daughter exclusively, hence thence to her single own child. This left Elias' father as a wealthless employee of his son's business.

When Elias was nine he got a flowerpot on his head from one of his little stepbrothers, lost his hearing, and a little later his sight. Despite the miraculous way he developed his sensory skills and feeling, growing to adulthood he remained a child in many respects. He spoke but "listened" by having symbols drawn on his skin. Reacting solely on affection he could not but attract only people in his company whom we all would like to have there. All the rest, no doubt including, according to Maarten, the entire Koopstad municipal council and spouses, and all regular visitors of the Koopstad patrician salons, automatically disqualified itself, leaving Johanna, the nurse who was, as his father discovered, his ideal, loyal and loving company, a dog who died after a while and, of all people, the one of the twin brothers who, when not yet much more than a toddler, had thrown him the flowerpot on the head. But he goes abroad to allow the author to let things in Koopstad escalate to a dramatic peak. Do not laugh! you novelist reading this, but go shame yourself for your own bungle.

Elias grows, acquiring a formidable body "with the limbs of an old Batouwer from the forests of the Rhine." (and think for a moment of proud me and that phone booth straight in the middle of where once those forests grew [more] ).

His hair curled and never got cut. He had the beautiful eyes of his father, though they did not see. The story goes on, switching between Elias in his modest but nice country house just outside town, with its scent of beautiful garden flowers, little cage birds lovely to touch, whom, Elias claims he can "hear" and the loyal loving Johanna, and, at a distance uncomfortable to walk, town centre with the cool clever one of the two twin brothers shuttling in horse coaches between the intricacies of home and work. The two parts of the story make the contrast of competition, profiteering, intrigue, show off, hate and jealousy of Koopstad and the restricted life of Elias, without worries and full of love. But the two parts stay in touch, for the twins run the formidable tea trade, without, at the start, owning a penny of it: employees of owner Elias. And everybody in Koopstad knew. It is a shame, such a fool with such a capital! He should be locked up. But after a surprising incidental appearance of his colossal deaf muscular body with those beautiful blind eyes under those light blonde curls, he immediately becomes the subject of frantic conversation - and even poetry! - under the young patrician daughters.

This can't stay as good as it is, you will say. Neither should it, in a good book. A meritorious Mephisto gently pushes the Koopstad-half of the twins, irritated by his slow pace of in-buying in the business due to his wife's prodigality, into a heavy speculative maneuvre (with Elias' money) during which the expected huge short run profits turn in disaster loss and murder.

Thus we end up, but thank God only in the last pages, in a crime scene, with all its known miseries, for it is impossible to write a good crime story: one can record a real crime, or concoct one's own. If recorded it will contain hosts of details liable to be used to accuse the author of sloppiness, unnecessarily early slackening of the bow of tension and missing other chances. So we apply makeup by omitting, moving forward or backward in time, explaining away and adding some accidental occurrences and in no time the mess has become unmanageable. On the other hand, if concocted, the author is alone with the problems of devising the proper thinking and actions for every character, the catalyzers and the stumbling blocs. And writing mankind turns out so bad in even just playing a virtual God that half of its readers finds holes and errors in timing and development. May be a good crime story could be forged by writing it on your 18th, keep sending it around for eighty years to experts and clear thinkers, every time closing the holes and errors discovered, before publishing it. Happily for the author but to the detriment of his readers, the first will find out the trash is marketable far before.

But may this author be forgiven! Portraying a deaf blind man, with his ensuing manifold retardation and his longing for what he very well knows he is missing, in such a way that you, maybe not really but surely in the book, would rather be him than the average successful patrician of Koopstad, is a merit that will not have given him grateful readers in our polders, but has prompted an awesome amount of Anglo-Saxon readers, assured this was not about them, to spend some dollars and time on it.

Maarten!, nowadays no apostles of your work are left, not even in the vast Anglo-Saxon language planes, but you have followed your own path. I feel lucky at this remarkable phone booth to have crossed it.

| Lingeblog Home |

| Previous |

| Next |

PHiLES home PHiLES home |