| Home |

Created 05-09-26

Last edited

15-10-27

The Domestic Market

In Africa, especially outside the cities, the market

serves a purpose very different from the what westerners are used to. The idea

is this: you live from the food crops of your land. You do

not need the market for your basic needs. However, there are additional needs.

The market is for additional needs only. You need money,

because the government will try to tax you, you need to pay school fees for your

children, the doctor, tick poison for your cattle, salt, matches, batteries for

you radio if you have one, soap, every now and then a new bicycle tire. The

market is there to sell your cash crop and buy your non crop necessities.

The strong story about my country of origin (Groningen) that I am used to tell

people here is that, say, a pig farmer grows pigs only. He does not grow

his own wheat, vegetables, he has no cow, no goats. He simply sells his pigs and

then goes to shops to buy everything he needs. This story meets real

astonishment in East Africa, but I am not ready!

I will continue, and tell them that the farmer is not allowed to slaughter and eat one of his own pigs. So, he sells all his

pigs and then goes to the butcher to buy pig meet to eat. This usually ends

every belief in my story in as far as any was left, though Africans are used,

for politeness, to hide that unnoticeably. After telling it myself several times,

even I myself start to doubt it. May be I was just told that story by a pig

farmer who does not find his pigs very tasty anyway.

THAT is another difference: goats, pigs, chicken, cows, sheep, they roam around

in Africa, unfenced, and as soon as they stop liking what is left of the

field they are grazing on, they move, and the only thing the herdsmen

(often little boys) does is

follow the animals. Not even the most expensive butcher in Europe can match

the quality of the meat we can buy here on every street corner. Cutting neatly is

usually not the butcher's hobby, so just buy large chunks, like a leg, an entire

muscle, the price is $1.70 per kilo anyway. There is abundant impeccable fresh

water fish, even cheaper.

Try our banana's, pineapple, avocado: they are not picked unripe to survive

transport of some weeks. We have not transportable delicacies like papaya fruits.

Our deep red tomatoes have a strong taste. You may find fresh red hot pepper on

a stroll at the side of the road (do not mix them up with strawberries!).

Our wines come from South Africa where in the last years they have succeeded in

matching the better French wine. It is sold cheaply in 5 l "teats", as we call

them, excellent quality, $6 per liter.

To quench out heavy thirst, we buy 0.5 liter of beer,

in and outside bars, for $0.8.

Label: No Nonsense, How To Sell Booze To Africans

In East Africa alcohol is used by the non-muslim

population only. In Tanzania, a muslim country, that is a minority. That

minority is not interested in the taste of alcoholic beverages. What matters is

how drunk you get for a dollar, and subsidiary, how you will feel the next day.

Advertisement gets straight to those points (see label above).

Alcohol is a big problem in East African (see

Family Life)

The government does not even seem to want to earn tax on alcohol: the Great

Scottish Malt Whiskeys are available for prices between $ 30 and $ 45, well

below the Edinborough shop prices.

Though booze and cigarettes are popular, everybody around me seems to fear one

thing like hell (or like the westerner nowadays is brainwashed to fear

cigarettes). They will never touch it: coffee.

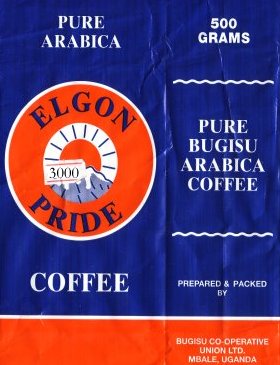

Coffee is for sale in shops frequented by wazungu, and the mountains (Ruwenzory, Elgon, Kenya, Kilimanjaro) yield excellent Arabica.

The market costs me more time than the African: the time it takes me to have them accept my offer of the normal price is longer. It is known to the sellers that wazungu often have no idea of prices, or no time to insist on having their dimes returned. One can evade this skin-tax, but, as it is with all types of tax evasion, you should be prepared to have attention and time.

Services

Services is the top strong point of African

markets. Average wage is something like $2 a day. The hair dresser costs to $

0.25. A good massage will be $ 3. Sex is between $ 3 and $ 15.

But I hear men complain their wives (many have more than one) bring $ 20 to the

hairdresser. That concerns complicated plaiting, straightening and modeling. I

did see three or four ladies working at one hairdo, they said they would

continue together working on it for five more hours that day. Still, that is only $

6 of

labor, so the rest of that $ 20 must be chemicals and the usually inserted

artificial hair.

Whatever, the westerner, used to quickly dispose of any malfunctioning utensil

should change his thoughts here: repairing is what you do in Africa, repairing,

repairing. And the African is the world master in the art of repairing.

Seemingly impossible repairs are done routinely. I have seen repair tricks

unheard of in Europe. Cars are driving for decades with carter leaks mended

with Super Glue and filter cigarette tissue. If you find something thrown away,

you will see it is absolutely impossible to use for anything (so, you will

understand now you will not quickly see cigarette filters laying idly).

Are you making something of metal, wood, stone, the cost is the materials. Not

the wage.

Few who know me will wonder why I spend an entire section on

Havana cigars.

Havana cigars are not available in East Africa (hawana means "we have

not" in Swahili). The Havana did have better

times. Not only before independence, but even a few years ago, when the Indian Radj

was still in charge of the tax free shops of the airports of

Nairobi, Entebbe and Dar es Salaam. I got them for the tax free price in one of

Radj's Kampala liquor shops. but Radj sold the shops. To another Indian, who

does not personally smoke cigars. This man sells to a Kampala shop an unknown

Cuban brand called "Los Statos De Luxe",

who sells for the bloody price of $ 3 a piece only if you buy

the 25 box. After a few weeks of stubborn abstinence I went for inspection. All

cigars in the box were broken. There was another box. It turned out to be in the

same condition. After a complicated story that he could not accept a reduced

offer because he was insured for this kind of calamities (who believes THAT??),

I left with 30 Los Statos for $1 a piece.

They are broken at the mouth side. The

tobacco is excellent, surely Cuban, the draught is comme il faut. I smoke

them from the wrong side and support, if necessary the wrapper with local

vegetation and a rubber band.

Toyota's the latest slipper fashion

The latest fashion in slippers are the "Toyota's", made of old radial tires. Seemingly primitive, its fabrication is sophisticated indeed: There is no planing of the surface. The model is shaped by selecting the proper cut from the tire. The stitching you see at the side of the slipper it the original tire factory stitching! Despite that, the slipper model is perfect. Price $1,-

The mobile phone revolution

On my first visit to Africa, April 1997, the mobile phone was unknown in Africa. The third time, December 1998 I took one, because I hoping the Italians working on Jinja's new electricity dam would have a satellite connection and a tower. But not only had the first network (Celtel) been installed in Entebbe, Kampala and Jinja and on the roads between them, the network already had a fierce competitor (MTN), and was nervously waving the $230 "entry fee" that was still in the shiny Celtel-folder. Nowadays, more than 30% of the East African families has a mobile phone, that means millions have to charge it elsewhere because they do not have electricity. Mobile phone charging has become a popular service. Mobile phone sales and repair can be found in every street of every town. The African rural family leaped from complete isolation into weekly chats with town dwelling relatives, children studying at far away schools and universities. Every African rural family made that leap, of course, for having a mobile phone implies having a mobile phone service for the rest of the village. Coverage in Uganda approaches 95% of the population. Who is still outside knows where to go and its near.

Insurance

There is a market for insurance. Its main field is the obligatory insurance of vehicles. National vehicle insurance is quite affordable, but international vehicle insurance - obligatory for international vehicle traffic - is 40 to 60 times more expensive! Guess why and how this comes. Free market insurance clearly has problems advertising itself. Who, in Africa, is interested in risks, let alone considering them and willing to pay them off? "Do not worry" type of advertisements grossly miss the mark: nobody worries anyway. The insurance advertisement phrase accommodating African brains the best I 've seen thus far is: "Rest Assured".

Where is the market?

Going from small to big we start with the

village. A village consists of a set of land owning extended families. They each have

a piece of land say of half a hectare - usually contiguous - on which they live on

a compound with houses and huts. This means that a "village" is not a

concentrated set of compounds. The compounds are scattered. Thus, an outsider is often

unable to see where one village stops and the next one starts. A network of footpaths leads to a road

connecting "villages". At the side of this road, women of the families often have

a small thatched booth where they bring there garden products (tomatoes,

potatoes, pineapple, bananas, jackfruit, eggplant, avocado etc.). Selling is an agreeable

family task for one of the women, because they can sit in the shade a nice clean

dress and chat with their sisters - often in the literal sense - in the

neighboring competing booth. Some of them have managed to raise some trade

capital to buy a stock of non village products like soap, masala, matches and

even Super Glue, which they sell along with their home grown products. Wheat and

maize go to the local miller, after which it is split up in a part for home

consumption and a part to sell to the wholesalers. Rice is handled the same

way.

Going from small to big we start with the

village. A village consists of a set of land owning extended families. They each have

a piece of land say of half a hectare - usually contiguous - on which they live on

a compound with houses and huts. This means that a "village" is not a

concentrated set of compounds. The compounds are scattered. Thus, an outsider is often

unable to see where one village stops and the next one starts. A network of footpaths leads to a road

connecting "villages". At the side of this road, women of the families often have

a small thatched booth where they bring there garden products (tomatoes,

potatoes, pineapple, bananas, jackfruit, eggplant, avocado etc.). Selling is an agreeable

family task for one of the women, because they can sit in the shade a nice clean

dress and chat with their sisters - often in the literal sense - in the

neighboring competing booth. Some of them have managed to raise some trade

capital to buy a stock of non village products like soap, masala, matches and

even Super Glue, which they sell along with their home grown products. Wheat and

maize go to the local miller, after which it is split up in a part for home

consumption and a part to sell to the wholesalers. Rice is handled the same

way.

For anything else you go to the nearest serious main road (still a dirt road) or

to the nearest small town. That could be tens of miles away. There, kiosk shops

look more serious, they are made of bricks and often are fenced with steel bars.

They might even have power, and a fridge with cold sodas, beers and ice cream.

There will be a butcher, with quarter goats, pigs, and cows hanging on display,

and a manipulated scale for weighing. More vegetables, a bicycle repair man,

even a car repair. You can get your hair cut (this is a highly developed and

specialized art). Many houses will advertise as "hotel", and indeed, you can

sleep there. May be there is even a transporter with a truck on hire to bring

your crop even further up to the bigger town or a real city like Kampala,

Mombassa, Nairobi, Dar es Salaam. There, of

course, nowadays one can buy anything on offer anywhere in the world. There are

shopping malls with all foreign goods on offer: any type of sun panel, battery,

mobile phones, internet-satellite phones, any spare part of any Japanese engine

is in stock, other spares come within a week from Dubai, original Italian osso

bucco, "Goudse" Dutch cheese (nowadays even locally produced by Dutch-East

African farmers), inline skates (though nobody knows where to properly use

them).

Charity, a disastrous market disruption

Sometime some western charity disrupts the markets: free clothes and shoes are sent by "good" people. One small attack of western benevolence and an entire local profession gets liquidated here. Not long ago, we had a ship here with beans withdrawn from a western market. You should have seen all those women who had been sweating for months on their bean fields to earn the school fees of their children! The tragedy and sorrow caused by western charity in Africa is only matched by the West's ruthless search and under-priced removal of mineral resources here.