Crtd 08-11-28 Lastedit 15-10-27

Caulking Part II

Arrival at Banda, beaching the dhow

Well, to be honest, we had another problem. A notorious one: Mwanza immigration. This time they could not, they maintained, make a passport for Johnny because they had run out of paper! After a few days, a "friend" in the immigration made a passport, but "not for passing through Kenya". So Philemon and Johnny avoided Kenya by taking a ferry crossing to Bukoba, at the East side of the lake in Tanzania (Map), and then cross the border directly to Uganda by bus. It worked. When Uganda immigration saw Johnny's passport, they did not even ask why and how he got it, but demanded USh 3000 extra (� 1.20). Philemon paid. They arrived. The next day we were off to Banda island:

To Banda, note Johnny's neat dress: jacket and basket ball shorts

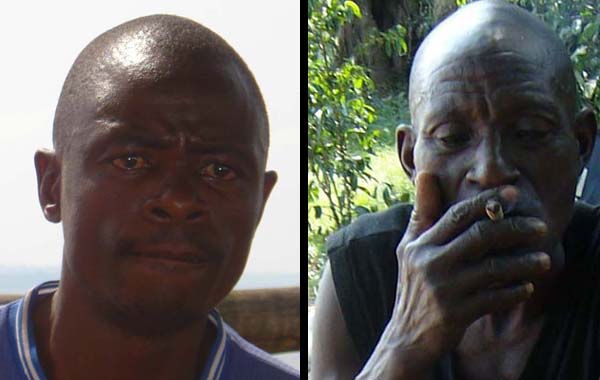

Arrival at Banda: Left Philemon concentrated on reducing speed,

throwing anchors and dropping sail.

Right: little later Johnny, a staunch weed smoker, attacks the abundant vegetation on the

island

Day one got lost with discharging the dhow. I found some moments to talk privately to Doi and Philemon, trying to satisfy my curiosity about what caused Philemon to give up taking Johnny on his first trip to Jinja. The latest wisdom is this: Johnny is by origin a Burundi village man, went to Mwanza, learned caulking, Kiswahili and even Kijita, the local language in the marine community, but no reading, writing nor even calculating. His mind is occupied with here and now in the most limited sense. Caulking is essentially hammering blanket fiber in the joints. When Johnny smokes weed he caulks, as goes the saying in Mwanza "like a machine gun", unaware of anything else. If you want him, agreements to be at some other place on some other time do not work. You have to grab and take him. That is what Philemon did on his second mission for a caulker. Day two:

Dominic's 12 ton (? label rusted) winch. Photo right: keeping balance by tying the back stays to trees far right and left of the dhow.

After a clumsy start using the extremely stretchy polyethylene anchor lines the keel dove up from the water and we could drill a hole for a metal wire

Dom's winch at full power, broke our steel wire connections twice.

Dhow out! Winching laterally to caulk bottom port side, under command of Johnny, to prepare for his job. The ribs' starboard edges are on old tires, keel goes in the air and gets supports. Ready for caulking on day three 14:00 hrs. Guess where Johnny started caulking after telling us to put the boat like this: at the starboard bow! But we say nothing: when we caulk, Johnny is the king.

I had been frantically saving change to hire 20 men from the

fishing village on the West side of this island, but despite many headaches over

problems, we got the dhow out without them. I

distributed the money saved on villagers among Johnny, Philemon and

Doi (7000 USh

each).

At sunset, after we looked long at the bottom, and marked

leaks we had seen from within and bad spots we now saw from outside, Johnny came

to me with a big smile, and a long Kiswahili story clearly concerning his wage,

but in the extensive florid vocabulary - too far fetched for my Kiswahili

training - that indicates that things now get serious. I knew this ritual

should last an hour or so to match the seriousness of the matter, lying anywhere

between � 150 and 250 for the entire job, deck included, and went with him to

Philemon and Doi to add weight to the meeting and for interpretation. The rule

is: do not worry to pay too little. The outrage will show you. But take care not

to bow for signs suggesting grave pressure to get seriously deserved over-pay,

or you will have yourself laughed at behind your back, as if you were one of

those easily to over-class silly whites coming to help Africa or bring aid.

Johnny, Philemon translated, set in high. He told us this was

a 500 000 Tanzania Shilling job, which for us friends, he would do for 400 000.

Philemon looked dark.

Do not worry Philemon, I said, he is on this island, he has no money, he has no

idea how to go home. I got Philemon smiling again. I had another strong point in this

negotiation: I can calculate. Johnny only knows what he gets for a

"line", which is one complete joint between two planks from the back to the

front of the boat. I know Johnny got 3000 TSh for a line on my dhow

three

years ago, so that could have gone up to 4000 at most. Thus, 400 000 pays for 100

lines. We have 26 bottom lines, 30 deck lines and 10 canoe lines. But Johnny had not

been told yet about the deck and the canoe job! In his amicable 400 000 offer

Johnny was considering the bottom lines only and had already declared more than

half of those as good, not to be redone. Thus he had been setting in on almost

20 000 per line, 5 times any reasonable price. But he was totally unaware of

that. He had just been putting a nice amount of zeros.

I laid my trump: I asked Johnny what would be his price for a line. Johnny

vaguely felt the danger, gave an elaborate speech, but no price for a line. I

went off, telling Philemon and Doi that we could talk as soon as Johnny had

a price for a line. After even less than half an hour Philemon came to say it was

5000. I retaliated by reminding Johnny that last time he worked for 3000, and I would now be ready to pay 3500. Moreover, he should realize that

here on Banda his food, beer and weed were free, and in Mwanza he had to provide

for all his daily needs using that 3000. After this simmered for a while I gave Johnny the choice: 5000 and paying for all food, beer and weed,

or 4000 and free living.

Johnny went for the 4000.

Thus I neatly reached my goal: paying slightly too much but avoiding ridicule.