Bert hamminga The Philosophy of Rated Assignments version date 991113 Questions

Non scholae sed vitae discimus

(Not for school but for life we learn)

This page is about the philosophy and ethics of motivation and organization underlying rated individual assignments, rated group assignments, and the influences rating systems have on motivation and ethics. Individually rated assignments, whether in money, in scores, or in scores yielding money, are notoriously Anglo-Saxon in cultural outlook (see the different valuations of measuring individual achievements in Different Capitalist Cultures). You find rated assignments in business and in universities as well. University students know about them because they do them almost every week.

When I became a student in 1969, my father, to his

own regret, earned too much for me to have Dutch state scholarship. He gave me money to

pay my rent and my food, but not for books. This was, he said, because he feared me to

spend my money going out and save irresponsibly on books. He remembered such

things from his own life as a student...

This regime of son-financing led to regular bills I sent to my father, with titles

of books, prices I paid and total amounts I charged him for. After considerably bleeding

book-money for a while my father started a discussion with me about modern (1969!) student

life. He said he got worried about me. Wasn't I too serious reading all these books?

University, The Netherlands 1948 My father vividly remembered himself

and his student friends "cutting open the books" (some pages used not to be cut

loose from each other by the printer) in March. From September to March, one followed some

ten hours of lectures, making some notes. Lectures were never before 10:00am which really

was 10:18hrs, if you came later and found the door closed you went home. Before March,

apart from these ten hours, it was parties, drinking, and sporting. In the doctoral

courses, you were not allowed to come for any exam if you had not followed the lectures

for two years! That was in the late forties.

At the end of the university year (in his doctoral at the end of two years),

my father had to dress up in tails for visits to five or so professors. They would have a

conversation, usually starting with my father communicating greetings from the

professors friends and promising to communicate greetings in the reverse direction. Then,

of course, my father had to answer some questions on the subject of the course. My father

actually did work on courses, not because of scientific interested, but because a bad

performance would be a shame to his family. Also, your fellow students typically felt

responsible for you if you lagged behind. One of my fathers lagging friends was told by

his group that he was not supposed to go out with them: he had to work. At midnight, out

from the bar, the group would walk to the guy's house to check whether his light was

burning. Everything OK, light burning, and the drunken gang would sneak past the house in

utter silence.

Professors typically were not too keen on questioning harshly: they knew the bright and

scholarly fanatic fellows would know the answers anyway, and he would not want the others

to bother him much longer with bad answers on second chance questionings by not letting

them pass. So, bad marks were scarce indeed.

University, The Netherlands 1969 When I started, my year did not have 20 students, like my father's, but 200. Professors did not even try to remember our names. They only very seldomly knew, like in my father's time, older relatives of ours to communicate greetings to. Usually they were complete strangers to our own social backgrounds: lots of student friends of mine whose fathers and relatives were working class felt strangers to the scene. But also professors increasingly were recruited from non intellectual and non elite backgrounds, so even for elite students, university anonymity set in.

For my father, who had business ambitions and no interest in science, a good exam result was partly needed to keep up his (family) image for the professor (and his family): the world was small. That could never, in 1969, have been a motivation for me to study my books well. Nobody knew me or my family, I knew nobody and nobodies family. Why work? Why learn?

The answer to that depends on the person. Of course, in 1969, just like in my father's time, there were students with "pure" scientific interest. Students who just wanted to pursue studies even if it would turn them into poor outcasts. That is the group to which I started to belong after a year or two, and it is not the most interesting group for the subject of this web page, because there always have been a few weird people like that, not very manipulable by the historical contingencies of social fabric of universities in some time, be it 1948, 1969 or 2000. The interesting group is that of the large majority of students who wish to prepare for a (non scientific) professional career. What was their motivation to learn in The Netherlands, 1969?

In 1969, a much larger part of the students thought of a career in public service than

nowadays. Many students, often coming from working class backgrounds, distrusted the

aims and benefits of business for Dutch society. When they thought of useful

professions, they thought of teaching, social work, labour union work, political jobs, in

general, jobs not designed to make a profit, but to be beneficial to society, to increase

the quality of life for people generally. They typically were studying a lot, but

complained that the official university courses did not provide the knowledge they

wished to acquire. They often privately convened to read non-prescribed books, discussing

their implications. There was, in these circles a lot of disappointment about the

university and they wanted reform.

In 1969, there also were lots students aspiring a business career, resisting bravely

frequent allegations that there ambitions were "dirty". Those who did not

have good family networks to get them in good jobs often worked very hard to acquire the

knowledge they thought they needed, others knew they could, and sometimes did, do more

easily, because due to social networks they would have no problems with their career. This

particular group is most interesting for us on this web page, because it faced problems

unimagened in 1948: since many exams were written exams now, and professors did not know

you, you had to work, not too keep up a family image, but simply to pass! That

is is the first time in history that people went for a sufficient "score" not

because they wanted to learn anything, but just because of their purely individual needs.

The historical origin of the rated assignment is this process of

University, The Netherlands 2000 The past decade witnessed the ongoing scale increase. Anonymity breaks new records every year: there are no lecturers anymore who know all their university colleagues, as in 1969 there still were. Individualization, and permeation of the ideology of individual interest and market thinking in The Netherlands kept trespassing limits. It is now the ultimate fashion to devise schemes for "scoring" and to put people in positions in which the value of their work is settled in view of their "score". Everybody has to "score" nowadays. Not only sporters and businesses, but also students, teachers, scientists, scientific research programmes and even whole universities and countries (The Netherlands "score" high in attractive low wage bills and low strike risks, Tilburg University scores "top" in this or that education ranking). And now, the big power struggle in the Dutch academic world is not to score but to be the one who makes the score boards for others, to be the scoreboarder.

The whole system is quickly climbing towards a summit of absurdness that would unimaginable if you would not see it happening before your own eyes. In 1948, my father was not allowed to any exam before having attended 2 years of courses. Now, 8 weeks of courses is often thought too long, so after 4 weeks the scoreboarders make a student's test.

The result is that people nowadays, as soon as no scoring is involved, stop doing anything and immediately start saving their forces. That is dangerous, especially if the scoreboarders make the kinds of scoring rules that are not likely to have any useful purpose except the scoring itself.

In the Asian "family" type of organization (read Cultures and Hierarchy and [#planned addition]), motivation is derived from being unconditionally accepted in the organization, and finding appreciation for any attempt you make to improve what contributes to the aim of the group. Now what happens if an organization hires scoreboarders? They will shift the attention of the members to scoring. Thinking how to contribute to the purpose of the organization and to improve your role in it as a member sinks drastically in priority. Matters seem to become simple: if you score, you do well, if you don't, you don't. But in truth, the real group aims get out of sight, alienation and inability to consciously and responsibly contribute to the group set in.

In the course philosophy of economy for international business, I mentioned in the lecture hall that I had overnight running software searching identical strings in all docs in some file. It helps me quantifying to what extent students use their own self chosen words, and to what extent they copy web pages and fellow students. I should not have said that: suddenly everybody was so interested in how this software operates that I had a very hard time indeed turning back to the teaching subject, philosophy of economy! Of course, this is not only blaming students. By adopting the method of scoreboarding, I as a teacher distract my students from the subject of my course. But what can I do? Before I introduced rated assignments, assignments were neglected completely. And students gave as a reason that priority was given to rated assignments of other courses.

Summarizing: scoreboarders create a cleft somewhere in the hierarchy of an organization. Down are the people who are forced to work for scores, up are the people who are allowed to keep using their brains.

Scoreboarders not only deprive scorers of genuine responsibility, morality and ethics.

They do more damage: The scoreboarders refer to market thinking as their

inspiration: scoring means you "settle" for "contracts". But

what they do is reintroduce communism: if you leave planning to responsible students, they

can make up for planning errors by moving workloads hence and forth their semester. Adam

Smith's invisible hand makes things come right by personal interest: it is best for you to

work 40 hours, no more, no less, and you can individually plan your semester accordingly.

Now what does scoreboarding bring about? Every course in the semester, say A,B,C,D and E

has assignment. Scoreboarders "plan" these assignments. Students are robbed of

their possibilities to individually match work loads to a scheme. Scoreboarders make the

scheme, equally for all students, like under communism. If you have smart scoreboarders,

they match such that, at least for the average student, you end up with week

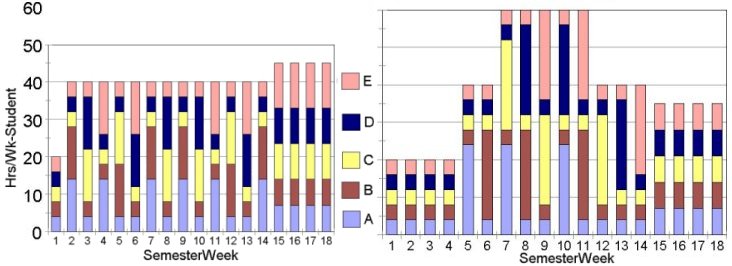

loads for the semester like the left hand graph below:

If a course's color has a large share in the stack for some week, that means that week this courses has a rated assignment. If the scoreboarders are not able to synchronize, as we all believe is impossible under such kinds of communism, you could end up with something like the right hand graph. For the average student. We not not even discuss individual differences. The scoreboarding paradox will now be clear: individualization is the end of individuality.

That may still sound strange enough to require more explanation: on the one hand our modern measurement and scoring techniques allow us to uniquely characterize every individual. This makes everybody unique. Nobody nowadays is able to get away from the scene of his crime, big or small. But this super individualism is at the same time the end of individuality: you are thought to be a unique code. But in that, you are like any other unique code. Your scores make you suitable for jobs like any other unique individual scoring similar on the relevant scores. Certain scores make you belong to a suitable target for certain advertisements, certain houses, etc, in general the marketing of certain products and services. The latest invention is "interactive TV": the information on the programmes you watch are sent to a computer that puts you on target lists for products likely to be interesting to viewers of such programmes. The interactive TV computer really gives you an "individual" treatment!

What gets lost

in forms like here at the right? By defining a general scheme of scores you may uniquely

define every individual, but you are unlikely to depict the individual as it would

like to see itself. The oppression is in the standards and concepts used to define

the scores. What happens in small closed communities, like a traditional African

community, is that the impact of one individual on the others is big enough for it to

set its own standards. In dealing with a tribe member every day, other member

discover his or her character, discovering a scheme for an individual person

while discovering that person. Every person gets to a far greater extent his or

her own "form", with scores for which others will not be measured. In a complex

large society consisting of millions of people, this true individuality gets lost and

human judgement degenerates, in the extreme to one general set of standards, one

scoreboard for everybody. These scores, like genetic codes, may well end up uniquely

specifying every individual but not at all to "knowing" this individual.

What gets lost

in forms like here at the right? By defining a general scheme of scores you may uniquely

define every individual, but you are unlikely to depict the individual as it would

like to see itself. The oppression is in the standards and concepts used to define

the scores. What happens in small closed communities, like a traditional African

community, is that the impact of one individual on the others is big enough for it to

set its own standards. In dealing with a tribe member every day, other member

discover his or her character, discovering a scheme for an individual person

while discovering that person. Every person gets to a far greater extent his or

her own "form", with scores for which others will not be measured. In a complex

large society consisting of millions of people, this true individuality gets lost and

human judgement degenerates, in the extreme to one general set of standards, one

scoreboard for everybody. These scores, like genetic codes, may well end up uniquely

specifying every individual but not at all to "knowing" this individual.

Scoreboarding is an unstable and quickly spreading disease: if some teachers engage in rated assignments scoreboarding, students start to underperform in those courses where this is not done. Thus many teachers, among them myself, are forced into scoreboarding in order to have students work for their preparation. The econometrics education of Tilburg University has decided against scoreboarding in the second year and higher, a brave decision allowing students to concentrate on learning and developing personal responsibility!

Go to: Questions

[planned additions: individual assignments, group assignments, crowding out, the underlying philosophy of motivation influence on morality in practice and ethics in theory]