Bert hamminga Back to: Index: Teaching

Docs

Page title:

ODLIVE is a highly unrealistic, abstract, even weird model. Therefore it is a good exercize in DME: you will never start believing it is real.

Suppose (DME always starts like that) we have an economy with 4 million equal jobs and 5 million equal people. 1 million of these people will be unemployed. ODLIVE is a model in which there is a free market determining who will be unemployed for and for what level of transfer income. The five all get 4 vouchers. Everybody is allowed to apply for jobs and try to reach an egreement for a contract with an employer. To enter in the job one needs 5 vouchers. The four most willing to have the job have to buy the remaining vouchers from the fifth. Each of them one.

In our real system, the unemployed are the ones that, though may be searching, did not find a job. In ODLIVE, the unemployed is the one who accepts the lowest offer for the vouchers. His preference to work is the lowest. In any country, consider all the ways total gross wage could be divided over net wage w and transfer income t to the unemployed. At the right extreme, w/t would be such that the unemployed just survive on t and the job-owners receive the rest as w. At the left extreme, the employed barely survive on w and the rest goes to the unemployed who receive a very high t. In a country in the left extreme nobody would want to work, in a country in the right extreme, everybody would want to work. Going from left to right every body passes a personal "critical value" for w/t at which he or she is starting to prefer to work. The "workaholics" will be the first, the extremely work shy will be the last. Everybody has its own critical value:

Exercize: Determine your own critical value. Think of the five people you know best. What would be their critical value?

Down is a model which assumes that critical values are distributed normally:

We have continuous lines (the "normal case"), intermitted lines (the "� down case"), and dotted lines (the "s down case").

Suggestion: print the graph before proceeding.

In the normal case, if you know that the number of jobs is J you can, going from left to right in the down graph add up the number of those who have reached their critical value and joined the ranks of those wanting a job. This yields a cumulative normal distribution. In the far right "everybody" (100%) will want a job. There is a point 1 where w/t is exactly at the ratio at which the number of job-seekers is equal to the number of jobs. This is the equilibrium transfer income of the voucher market: is the voucher price lower, too many people will prefer a job, and unwilling to sell their vouchers. The voucher price will rise, w/t will come down till point 1 is reached. Is the voucher price is higher than the one associated with 1, too many people will sell vouchers, their price will go down until point 1 is reached.

If labour looses interest of people. That would be the "� up case" , not shown in the graph: the average critical ratio (the peak in the upper graph) would shift to the right, the demand for jobs will go down, less people want to be owner of vouchers. The voucher price will go down. Until...the same number of people work! But now they have paid less for the vouchers, hence enjoying a higher income. The number of workers remains the same, but their money compensation has increased, which is just, because the sacrifice of working is felt heavier by everybody. .

The opposite case is the � down case (the interrupted line). People gain interest in working. Working comes to be the fashion. When you're not working, you're out. The peak of the � down curve in the upper graph is to the left. The voucher price goes up until point 2 is reached. The the same number of people works, the same number is unemployed, but to be unemployed now is a greater sacrifice and is compensated higher accordingly.

The s down case makes the normal distribution steeper. This could be caused by increasing conformism. Preferences are less diverse. Everybody wants to a greater extent the same.

Exercize: When conformism grows, what happens on the voucher market with equilibrium voucher price and equilibrium wage transfer income ratio w/r?

As an example of DME we should start to make a list of assumptions that are strong and unrealistic and hence would be nice to relax:

1. The rate of unemployment is fixed

2. Work comes only in full time jobs

3. All jobs are equal

4. Everybody is fit for every job

Exercize: Think of more assumptions involved

What is very characteristic of DME is that if one "gets into" the story, one tends to forget about a lot of assumptions made. Also, many assumptions made are only discovered after one starts to think of the model introduced, that is, many assumption are "hidden" or "tacit". Many great findings in DME economics started with the discovery of a tacit or hidden assumption of an existing model.

Relaxing 1. The rate of unemployment is fixed

Consider the rate of unemployment changing: one million more jobs are lost. Now we give not four, but only three vouchers to everybody and you will need five to occupy a job.

These ratios can be adapted to every rate of unemployment

Relaxing 2. Work comes only in full time jobs

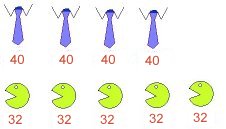

Consider 40 hours per week jobs that are flexible to the hour. In the case of 4 million jobs and 5 million workers, there would be 32 hours work for everybody.

Now, we can give everybody a 32 vouchers, and you need a voucher for every hours you work. There is no trade if everybody chooses to work 32 hours. If some work more and other work less, these people trade vouchers. The market retains its basic mechanism.

Relaxing 3. All jobs are equal and 4. Everybody is fit for every job

Those are hard ones. Think of a hospital. It has nurses and doctors. Suppose the nurses

do the work, and are badly paid. Suppose the doctors do few things more than watching

patient's data sheets, giving orders and receiving Nobel prizes. Suppose they have very

high wages. So, the nurses will sell their vouchers and stay home. For docter's jobs,

there is a long line of applicants.

What would the management of the hospital do? Increase the nurses' wage until they come

back. With what money to pay the nurses additionally? With money withdrawn from docter's

salaries. There are too many aspirants there anyway, you can lower the salary until you

have a sufficient number of able docters willing to do the job. The rest of the money can

be used to compensate nurses for their heavy work. The voucher system makes nice work

payed low, and bad work payed high, which is logical in a rational world..

But what if the bordering country does not have the voucher system? There will be a doctors drain and nurses affluence as a result, unless labour movement is restricted.

Exercize: find more unrealistic assumptions involved in ODLIVE and trie to relax them.

Exercize: How about 90% unemployment? Will the voucher market still work in a mechanical paradise where machines and computers do almost all the work and humans are only needed for consumption?

Exercize: Would Popper, Kuhn and Lakatos consider what we have done here as "science"? Is it "economics"? Give your reasons.