Bert hamminga The Modigliani-Miller Theorem

Presentation for teaching purposes of part of Cools, K., hamminga, B. and Kuipers, T. (1994) "Truth Approximation by Concretization in Capital Structure Theory" in: hamminga B. and N.B. de Marchi (eds) Idealization VI: Idealization in Economics. Poznan Studies in the Philosophy of Science and the Humanities, Vol 38. Amsterdam, Atlanta: Rodopi 205-28.

1 Introduction

"How do firms choose their capital structure?" is one of the most important issues in corporate finance - and one of the most complex. The "capital structure" is the ratio between debt (money borrowed by a firm at a fixed interest rate), and equity (money invested in the firm by shareholders that own the firm, have full posession of its assets and profits, and thus are the residual claimants)5). Corporate finance is part (the other part being investment theory) of financial economics, which is a branch of applied micro economics and therefore based on neoclassical utility theory. In additon to standard utility theory assumptions, in corporate finance it is assumed that the goal of a company is to maximize shareholders' wealth (= utility) i.e. maximize the market value of equity. Given the above mentioned goal of the firm, the answer to the question "How do firms choose their capital structure?" can be rephrased as "Which capital structure maximizes the value of the firm?" or "Can the value of the assets be increased by an optimal financing policy of the firm?".

In 1958 Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller wrote their seminal paper on the issue of the optimal capital structure. Although for some decades the paper has been the subject of intense scrutiny and often bitter controversy, and Franco Modigliani once stated that "I must confess that ... my two articles with Miller on corporate finance are written with tongue in cheek, to really make fun of my colleagues. " (Klamer (1983), p. 125). Most of these controversies can now be regarded as settled: the essential results of the paper have overcome. Moreover, the results, often called the MM propositions, have spread beyond corporate finance to the fields of money and banking, fiscal policy and internatinal finance (for examples, see Miller (1988)). And finally, the scientific community has recognized the importance of the paper by awarding both authors the Nobel Prize in economics (Modigliani in 1984 and Miller in 1990).

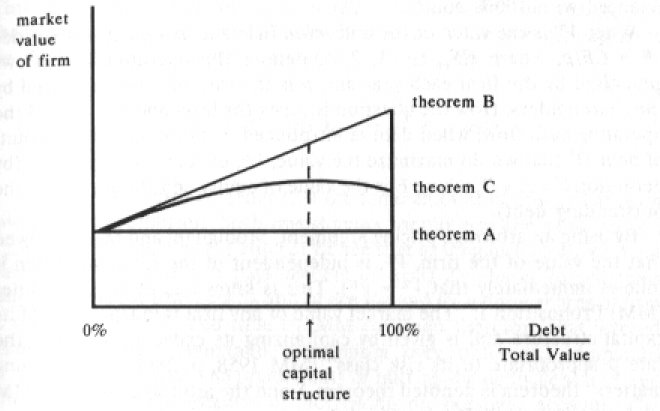

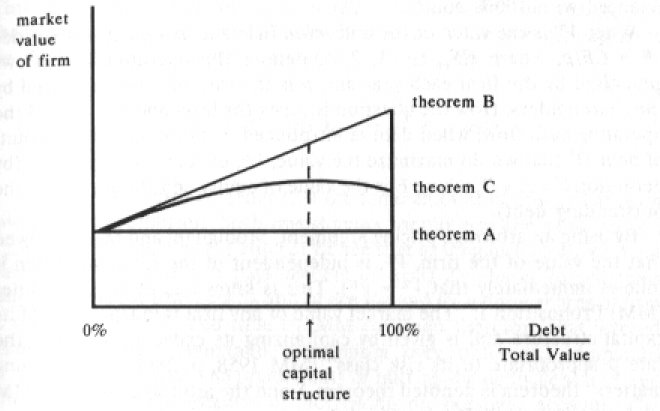

Proposition I of MM has become the first step in capital structure theory and is sometimes called the 'nothing matters' or 'irrelevance' theorem. It states that, as an implication of equilibrium in perfect capital markets, the value of a firm is independent of its capital structure (that is, its debt/equity ratio). In proving this proposition they used a then-novel arbitrage argument, which is now common throughout finance. The second step was also made by MM, first in their 1958 paper, but corrected in Modigliani and Miller (1963). It says that, when corporate taxes - interest payments are tax deductible - are introduced in the model, 100% debt financing is optimal. The intuition behind this being that the more debt, the less taxes a firm pays, and therefore the more money - thus value - is left for the financeers (shareholders and debtholders) of the company. This result was extremely puzzling, since in real world one never observes firms with 100% debt financing. The third step in capital structure theory was first suggested by Baxter (1976) and later formalized by others. Now, bankcruptcy costs are introduced. These costs consist of payments that must be made to third parties other than bond- or shareholders when the firm goes bankrupt, such as trustee fees, legal fees, costs of reorganisation, etc. These "dead weight" losses associated with bankruptcy cause the value of the fim to be less than it would have been otherwise, namely the value based on the expected cash flows from operations. And since the change of going bankrupt is higher when a firm is financed with more debt, there are costs involved with debt financing. The tradeoff between the tax advantage of debt and bankruptcy costs associated with debt results in an optimal capital structure, the so called balancing theorem.

To summarize, in a perfect world - without taxes of bankruptcy costs - the debt-equity ratio is irrelevant for the value of the firm (theorem A). When the imperfection of corporate taxes is introduced, 100% debt financing is optimal, i.e. maximizes the value of the firm (theorem B). Finally, when also bankruptcy costs are taken into consideration, there is a cost to debt financing and an interior solution for the optimal capital structure emerges; a debt/equity ratio somewhere between 0% and 100% maximizes the value of the firm (theorem C). Theoretically, it would also be possible to consider a world with only the imperfection of bankruptcy cost (and no corporate taxes), in which case 100% equity financing would be optimal (theorem D). In Figure 1 all four theorems are illustrated.

Figure 1: optimal capital structure

Now, let us go more into the details of the famous MM "Proposition I".

2. Modigliani and Miller's "nothing matters", theorem A.

The value of the firm, equals the net present value, NPV, of future expected cash flows (that is: net receipts of money, after deduction of all cost exept interest payments). The NPV of a

t-period 'project' can be written asNPV =

�tt=0 CFt / ( 1 + r ) t, where CFt, is the cash flow on time t and r is the required rate of return or discount rate. r is determined by the time value of money (the risk free interest rate) and the riskiness of the expected cash flows, CF. In case of a perpetuity (i.e. an infinite, constant stream of cash flows) the NPV

can be written as

.![]()

An unlevered firm is a firm that has no debt, in ohter words, it is financed with 100% equity.

When VU is the value of the unlevered firm and assuming

perpetuities

![]()

where CFt, t = 1, 2, ... denote the operating cash flows generated by the firm

each year and r is the rate of return required by the

shareholders. How the question is, given the level and riskiness of the operating

cash flow, when debt is introduced, is there a certain amount of debt D* that would

maximize the value, VL, of such a levered firm. (by definition V � E + D, where E is the value of equity and D the value of

the outstanding debt).

By using an arbitrage pricing argument, Modigliani and Miller showed that the value of the firm, VL, is independent of the ratio D/E (then it follows immediately that VL = VU). This is known as Modigliani-Miller (MM) Proposition I: "The market value of any firm is independent of its capital structure and is given by capitalizing its expected return at the rate

r appropriate to its risk class" [MM (1958) p. 268). This "nothing matters" theorem is denoted theorem A and the arbitrage argument MM used to prove their Proposition I can be summarized as follows. Using the same notation as MM, V1 is the value of an unlevered firm (only equity) and V2 is the value of a firm that has some debt in its capital structure, but is identical in every respect to firm 1, most notably its X, the total annual return (cash flow), and r, the interest charge, are the same as those of firm 1. Hence for the annual return of both firms we can drop 1 and two and write "X".X1 = X2 : = X

D is the market value of debt and S is the market value of equity.

Then: V1 = S1 and the income available for the stockholders equals X

V2 = S2 + D2 and the income available for the stockholders equals X - rD2

Now consider an investor holding s2 dollars' worth of the shares of firm 2, representing a fraction

a of the total outstanding stock, S2.So, the investment,

aS2, gives the investor a return ofY2 = a(X - rD2) (1).

Now, suppose the investor sells his

aS2 worth of company 2 shares and buys an amount s1 = a(S2 + D2) of the shares of company 1. He can do so by utilizing the amount aS2 realized from the sale of his initial holding, and borrowing an additional amount, aD2, on his own account. This gives him a fraction s1/S1 = a(S2 + D2) / S1 of the shares, and therefore earnings, of firm 1. Taking into account the interest payments on the personal debt, raD2, the return Y1 to the investor, will in this case be given byY1 =

[a ( S2 + D2) / S2 ]* X - r a D2 = a [V2/V1] * X - r a D2 = a [ (V2 /V1) * X - r a D2] (2)Since in both cases ((1) and (2)) the same amount of money has been invested, in equilibrium both investments should give the same return, Y1= Y2. (If not, investors would prefer one of the firm's 1 and 2 shares to another, which would make the price of these shares change until there would be no more such a preference. This final state is what is by definition called the equilibrium state). Comparing now (1) and (2) we see that as long as V2 > V1 we must have Y1 > Y2, so that it pays owners of firms 2's shares to sell their holdings, thereby lowering S2 and hence V2; and to acquire shares of firm 1, thereby raising S1 and thus V1. MM conclude therefore that levered companies cannot command a premium over unlevered companies with identical annual return X because investors have the opportunity of putting the equivalent leverage into their portfolio directly by borrowing on personal account. The possibility to borrow on personal account is a crucial element in the proof of the theorem and has become known as 'homemade leverage'.

A similar line of reasoning is followed for the other possibility, namely that the market value of the levered firm V2 is less than V1(MM (1958), p. 270).

It is important to realize, that the MM Propositions only hold in an ideal, perfect, world, which has become known as the MM world. MM implicitely or explicitly assumed that:

1. Capital markets are frictionless.

2. Firms can lend at the risk-free rate (riskless debt)

3. Individuals can also borrow and lend at the risk-free rate

4. There are no costs to bankruptcy

5. Firms only issue two types of claims: risk-free debt and (risky) equity

6. All firms are assumed to be in the same risk class

7. There are no taxes

8. All cash flow streams are perpetuities (i.e no growth)

9. Corporate insiders and outsiders have the same information (i.e, no signalling

opportunities)

10. Managers always maximize shareholders' wealth and do not expropriate in any way other

stakeholders of the company (i.e, no agency costs)

11. Contracts are complete and can always be enforced

What happened between June 1958 and today is that each of these assumptions has been relaxed in order to study the effect of every single imperfection on the MM results. The driving force behind this 'theory development' is the gap between theory and practice. Especially with respect to MM I the gap was immense. All real world debt-equity ratios vary within a certain range of, let's say, 60% to 20% debt. In fact, MM themselves ended their 1958 article with inviting others to study the relaxation of assumtions: "These and other drastic simplifications have been necessary in order to come to grips with the problem at all.", followed by the curtain line of the paper "Having served their purpose they can now be relaxed in the direction of greater realism and relevance, a task on which we hope others interested in this area will wish to share." (MM (1958), p. 296).

Essentially, ever since June 1958, theoretical papers on capital structure have been concerned with relaxing one or more assumptions. The form it has taken in the last decade, however, is to introduce new techniques (e.g. game theory) and new imperfections (e.g. incomplete contracts), which only implicitly or without realising were assumed to be absent before. The first step, however, was taken by MM themselves in their 1958 paper, but corrected in MM (1963).

3 Modigliani and Miller with corporate taxes, theorem B.

In MM (1958) the first imperfection was already introduced: corporate taxes (Modigliani and Miller made a technical correction in 1963). The important thing about corporate taxes is that interest payments are tax deductible. MM (1963) showed that when corporate taxes are included, the value of the levered firm is equal to the value of an unlevered firm plus the present value of the tax shields associated by debt: VL = VU +

tc D, where tc is the corporate tax rate. In this way the capital structure that maximizes the value of a firm consists of 100% debt. This result we call theorem B; a corner solution where full debt financing is optimal.In 1963 MM again used an arbitrage argument, similar to the one in 1958, to prove 'Theorem B'. Following their own line of reasoning, their 1963 proof can be summarized as follows. Using the same notation as MM,

t is the marginal corporate tax rate,X is the (long-run average) earnings before interest and taxes generated by the currently owned assets of a given firm in some stated risk class,

X

t is the after-tax return,R is the interest bill, equals rD in the 1958 notation, and

rt

is the rate at which the market capitalizes the expected returns net of tax of an unlevered company in a certain risk class.Then X

t = (1 - t)(X - R) + R = (1 - t)X + tR.This suggests that the after-tax return consists of two components: (1) an uncertain stream

(1 -

t)X; and (2) a sure stream tR. Therefore, the equilibrium market value of the combined stream can be found by capitalizing each component separately. More precisely, the market capitalizes the expected returns net of tax of an unlevered company in a certain risk class at rate rt, i.e.rt = (1 - t)X / Vu or Vu = (1 - t)X / rt.

And since r is the rate at which the market capitalizes sure streams, r is the appropriate discount rate for the tax shield tD.

Then we would expect the value of levered firm with a permanent level of D to be

VL = (1 - t ) X / rt + t R / r = VU + t D (3)

Modigliani and Miller show that if (3) does not hold, investors can choose a more profitable portfolio by switching from relatively overvalued to relatively undervalued firms.

Suppose first that unlevered firms are overvalued, i.e. VL -

tD < VU. An investor holding m dollars of stock in the unlevered firm has a right to a fraction m/VU of the eventual return, i.e. YU = (m/VU)(1-t)X.Consider now an alternative portfolio obtained by investing m dollars as follows: the portion ({SL / (SL + (1 -

t)D}) . m is invested in the stock of the levered firm, SL, and the remaining portion, ({(1 - t)D / (SL + (1 - t)D)} . m) is invested in its bonds (= debt). The stock component entitles the investor to a fraction {SL / (SL + (1 - t)D)} . m of the net profits of the levered firm, which equals {m / (SL + (1 - t)D}) . {(1 - t)(X - R}. And the holding of the bonds yields {m / (SL + (1 - t)D)} . {(1 - t)R}. Hence the total return from the alternative portfolio is YL = {m / (SL + (1 - t)D)} . {(1 - t)X} and this will dominate the uncertain income YU if, and only if, SL + (1 - t)D � SL + D - tD � VL - tD < VU.Thus, in equilibrium, VU cannot exceed VL -

tDL, for if it did investors would have an incentive to sell shares in the unlevered company and purchase the shares (and bonds) of the levered company.A similar line of reasoning is followed for the other possibility, namely that the market value of the levered firm, VL -

tD, is less than the value of the unlevered firm, VL. (See MM (1963), p. 427-8).Theorem B was even more irrealistic than MM without taxes. There exists not a single firm which is voluntarely financed with 100% debt. Therefore the process of relaxation went on and in the beginning participants in the research programme were mainly looking for disadvantages of debt financing in order to come up with an internally optimal capital structure.

From MM theory it follows directly that the debt/equity ratio is irrelevant for the value of the firm, no matter the risk class. Hence assumption 6 was relaxed without theorem A or B being effected.

The factor that, intuitively, one would guess will alter the 100% debt corner solution will probably be the relaxation of the risk free debt assumption. In real life, when leverage (debt financing) increases debt becomes more risky since the chance that not all debt obligations can be met increases and debtors will therefore ask for a higher interest rate. Consequently, one would maybe say, since more money has to be paid to debtholders, that the value of the firm will decline if the debt/equity ratio rises. However, the introduction of risky debt does not change the MM propositions; it has no impact on the value of the firm. Stiglitz (1969) first proved this result, using a state preference framework, and Rubinstein (1973) provided a proof, using a mean-variance approach. Therefore, the introduction of risky debt cannot, by itself, be used to explain the existence of an optimal capital structure with a debt-equity ratio between 0% and 100% (a so called "interior" solution).

4 Bankruptcy costs, theorem C (an interior solution)

As we have seen, in a world without transactions costs risky debt does not affect on the value of the firm. However, when bankruptcy costs are taken into account, things are beginning to look differently10). Baxter (1967) was one of the first to suggest the existence of an internal optimal capital structure, based on bankruptcy costs: "If, ..., bankruptcy involves substantial administrative expenses and other costs, and causes a significant decline in the sales and earnings of the firm in receivership, the total value of the levered firm can be expected to be less than that of the all-equity company.". Since then, more sophisticated treatments have been offered by Kraus and Litzenberger (1973), Scott (1976) and Kim (1978).

When bankruptcy costs are considered, the value of the firm in bankruptcy is reduced by the fact that payments must be made to third parties other than bond- or shareholders. Trustee fees, legal fees, and other costs of reorganization or bankruptcy are deducted from the net asset value of the bankrupt firm and from the proceeds that should go to bondholders. Consequently, these "dead weight" losses associated with bankruptcy may cause the value of the firm in bankruptcy to be less than the discounted value of the expected cash flows from operations. This fact can be used to explain the existence of an interior optimal capital structure: theorem C.

5 Later developments

The next step in capital structure theory was the introduction of personal taxes [(Miller (1977)]. Miller showed that, again, a "nothing matters" situation arises when you combine corporate and personal taxes. Since capital gains (equity income) are not taxed, but interest is taxed at the personal level, for the investor, who ultimately determines the market value of a company, there might even be a tax disadvantage to debt financing. Then, a new strand of literature was started by the famous Jensen and Meckling (1976) paper. They introduced the so called agency theory in the world of corporate finance, which relaxes the assumption of no conflict of interest between different parties, especially management, shareholders and debtholders. In particular, managers do not always act in the interest of the shareholders and consequently the goal is not always to maximize the value of the company. The paper shows that, based on these agency problems and without assuming taxes or bankruptcy costs, an optimal capital structure can be explained. One year later Ross (1977) introduced the existence of asymmetric information in capital structure theory. Assuming that managers have more information about the expected returns of the company than outside investors, he argued that greater financial leverage can be used by managers to signal an optimistic future of the firm. In the same year Leland and Pyle (1979) used the existence of asymmetric information to show that the firms value if positively related to the fraction of the owners stake in the company and therefore the firm will have greater debt capacity and use greater amounts of debt.

Since the late seventies, until the late eighties, virtually all research concerning capital structure issues has been concerned with agency and/or asymmetric informational issues. Since the middle of the eighties, interrelations between financing and investment decisions (e.g. Titman (1984) and capital structure choices in relation to takeovers (e.q. Harris and Raviv (1988)) have been studied. Most recently, the assumption of comple contracts is relaxed. Instead, contracts are assumed to be oncomplete, i.e. they don't specify precise provisions for every conceivable future event (e.g. Cools and Zon (1992)). And apart from the theoretical literature hundreds of papers try to empirically test all the different capital structure theories.11)

Go to: Reconstruction of the Theory Core of the Modigliani Miller Programme