Bert hamminga Knowledge version date 991109 Goto: Questions

"I know...." is a common language expression in all cultures of the world. To refer to the set of things known as "knowledge", is also something generally understood world wide. Different cultures, however have different concepts of "knowledge". Though most languages have a rough equivalent to the English word "knowledge", a closer look reveals differences, usually originating from differences in

The way you use knowledge; why you think you need knowledge

The way you acquire knowledge:

-

how knowledge comes to you, or

how you go to get it

-

how you feel justified in

believing that what came to you, or what you got, indeed is "knowledge"

Three types of knowledge

One can speak of

Philosophers often reserve the term "objective knowledge" for state of the art, wrongly suggesting that this knowledge is more "objective" and the other two types of knowledge are less "objective" (some philosophers use a forth type knowledge concept: all things that could be known, a concept that we shall not investigate, although of course after something became known we shall have to admit that apparently it is possible to know it -quite philosophical isn't it?).

1. Personal knowledge acquisition

Personal knowledge acquisition can happen in three ways, not perfectly distinct from one another:

Genetic.

At birth both animals and humans have certain kinds of vital knowledge. For instance, they

know how to eat and make the sounds and gestures necessary to make clear to their

parents what they need at some moment. In fact, the development of a a young person or

animal largely follows genetically triggered patterns, by which parents know they have to

feed, laugh, make sounds, speak and repeat words. Also, most of the things parents do to

raise a young child is not taught, but comes "spontaneously". So,

behaving as a parent is largely a genetic thing. Children have genetic knowledge on how to

develop, and parents have genetic knowledge in how to raise. Admittedly, the term

knowledge has no clear borderline with "body function". A baby could be

said to genetically "know" how to call its mother, but it would not

conform our idea of "knowledge" to say it genetically knows how to keep its

blood in circulation (by using the heart muscles). In between these two there are a lot of

things babies do that one may, and another might not call "knowledge". In the

common use of the term "knowledge", the existence of genetic knowledge is beyond

reasonable doubt, and without it, no other knowledge acquisition would be possible.

By doing (trial and error).

This type is well known in daily life and in science: though a baby certainly does

not know at birth that tossing a rattle yields a sound, it will know not long after. Some

babies might have been taught so by their mother, but if the rattle hangs low enough, no

mothers are needed for a baby to learn this. First, the baby will accidentally touch it.

After a while it will clearly deliberately produce the sound of a rattle tossed.

That is a paradigm example of learning by doing. Those whose mind remains young become

cooks, making lovely recipe's, and experimental physicists, building huge particle

accelerators of billions of dollars just to see what sound the tossing of particles will

make.

By being taught.

Nobody can become a professional cook or experimental physicist without being taught.

That involves action by others intended to make you understand something or capable

of doing something. In being taught, humans differ most from other animals. Human genes

are not known to have changed much in the last 10000 years. Human life, mode of

survival, and technique did and it did so dramatically (who after all invented

that good habit of hanging a rattle in a baby's cradle?). Since human genes are (almost)

identical all over the world, it is in being taught that culture differences come

about. Teaching has many degrees of sophistication. In its simplest form a

"teacher" might be only dimly aware that he is a teacher: a pupil simply copies

what he sees someone else doing. Examples of the other extreme are what happens to you

after you are admitted to a fighter jet training or a philosophy course.

In 1973, birds in Scotland started to tear aluminum foil covers of milk bottles with their beaks. After that, they took a taste of the the milk. The habit gradually spread south, and two years later London birds had acquired this know how. Making fire, using wheels, forging iron, building brick walls, shooting canons, printing micro chips, all such human techniques spread in a similar way.

In more sophisticated forms of teaching (philosophy and fighter jets, but also sophisticated programmes for infants), it is mainly the teacher who gets smarter, by thinking how to influence pupil and how to order the instruction programme. That is because it is the teacher who has the lead over the pupil in absorbing the culture.

Teaching itself is done differently in different cultures. Many traditional cultures rely exclusively on oral communication. One does not write and read, one learns new things by doing, and relies on being taught and watching. As long as everybody in your group has to learn roughly the same, this is a good way to hold the group together. The oral method however is less effective than the literal method once different people have to learn different things as a result of division of labour and even, as we now have it in Western cultures individualization of tasks.

Think of a video recorder manual. If your friend knows the recorder and explains you, you'll control the thing in five minutes. Reading of the manual might take you a full evening. So, oral communication is better. Unless..... almost everybody buys another type of video recorder. You could not afford a teacher sent by your video seller for oral instruction! Western culture is since long in a spiral of individualization of tasks and individualization in making available of information. Traditional cultures have very little individualized teaching packets and hence can profit from the speed of oral teaching.

2. Group knowledge: the Western economic concept of knowledge

The Western business concept of knowledge comes out easily if you ask economics students in a lecture hall about the role of knowledge in economics.

What knowledge does to your business

What knowledge does to yourself

Thus, knowledge gives a business power in the market, earning capacity. Businessmen have substitution possibilities: they can learn yourself, have your own people taught or hire knowledge externally. The alternatives have costs and benefits that have to be weighed for a balanced decision.

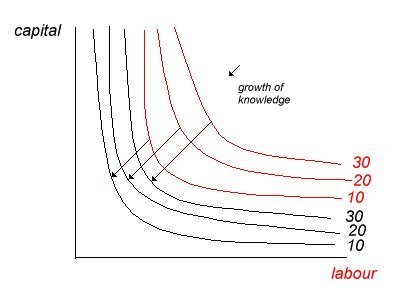

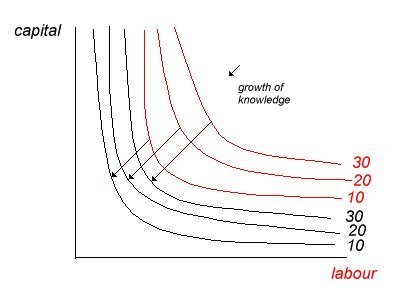

The standard economic modeling of knowledge is in a production function where the amount y produced depends on the amount of factors of production, say labour l and capital c used:

y = at . lk. c(1-k)

is a so-called Cobb Douglass production function. The red "10" line below forms all combinations of labour and capital input that allow you to produce 10. Similarly the points on the red "20" line give the combinations that allow you to produce 20, and the same for the red 30 line. If your knowledge grows, and you use it for improving your technique of production, same amounts 10, 20 and 30 can be produced with less labour and capital, so all lines shift down to the left. The black 10, 20 and 30 lines are where the red ones went as a result of knowledge increase. at has risen. Thus knowledge is modeled by a rise of at.

3. The "knowledge of mankind": state of the art.

Finally there is a concept of "available" knowledge. Scientific research is

usually understood as directed to the growth of available knowledge. The acquisition of

knowledge nobody thusfar had.

Though scientific research is done at universities and university research institutes, the

larger part of the famous results in the history of scientific research has been achieved

by others, outside universities. These include private amateurs, business people,

craftsmen, monks, military men and many others, many of whom were not educated and trained

at universities but by themselves. This should not be surprising: universities and

teachers are known for their traditions and supposed to hand them down, and the

primary thing path breaking research usually breaks is tradition. When yo do that

in a university job you can easily get trouble.

Galileo had to leave his university for lack of money. Descartes took a law degree, but then quickly isolated himself to live an anonymous bachelor's life, almost nomadic, moving to another place yearly on average. Einstein got bored at his high school and left without passing a final exam. Later, though, he entered the academic world. Keynes never felt like having a university career and forced the university economics professors to take his theory seriously by first convincing politicians and the general public directly. Bill Gates, 19 year old, got sick of Harvard university after a few months of his first year and left.

Among the scientific pioneers linked to universities and embedded in university tradition are Newton and Adam Smith.

Philosophy of science chiefly deals with this last type: the acquisition of knowledge yet unavailable. Since philosophy of science is chiefly a product of academic professors, it tends to have a university bias, though many good philosophers in the trade recognize the weak contribution universities traditionally have made to the growth of available knowledge.

Go to: Questions about this page

[Planned additions

O West: Knowledge is equal for everyone, generally valid, there is only one truth.

O Africa: Knowledge get diversified as passed on, like every biological (forms of face)

and technical (form of tools) property

O (genetic, #afr: or gift from "testator" to "heir"

]