PHiLES home

PHiLES home

| Greetings Home |

PHiLES home PHiLES home

|

Crtd 10-08-01 Lastedit 19-10-13

Candide, Voltaire

Satirizing "Optimism"?

Leibniz.

Many learned authors choose to teach their readers the views of other scholars. A lofty ambition, usually for the purpose of either supporting or attacking those views. But description conflicts with defense and attack. The conflict lures the "teacher" into what he considers as "improving" the described views if he set out to defend them, or to weaken them if that facilitates the attack. The larger part of reading and writing in academic circles is devoted to correcting again the results of such petty intellectual corruption. The great Leibniz, co-inventor of the mathematics of differential calculation, and the first to introduce the binary number system, fell victim to an attempt to have his back side bared by Voltaire, in a very amusing short story Candide. Of course, for such purposes the philosopher's views should be simplified to one sentence, easy enough for a mid-eighteenth century bookshop visitor to understand: Leibniz' impersonator in Candide, Pangloss, claims that we live in the best of possible worlds (he has proven it!). Leibniz indeed wrote so, and his position seems absurd to every drunk stumbling over a stone ("Is it best I get drunk and then stumble over a stone?"). Leibniz however did not write for drunks and meant something totally different, the logical complexity of which we do not need to dwell on since it has nothing to do with Voltaire's Candide.

Scholarly opinions differ as to just what made Voltaire have a go at Leibniz and misrepresent his doctrine to such naive dimensions. In my view Voltaire was launched by his sometimes counterproductive but usually profitable instinct to rally the public behind him by satirizing unpopular views in marketable ways. He acquired immortal fame with that, and Candide is one of his top successes. Leibniz himself was far too complicated and boring for Voltaire, a quick, witty Frenchman, a born entertainer, indeed a successful playwright, who could speak and write faster than he thought. Apart from his immense work, Voltaire dropped at least 20 letters a day in the mail. I can not believe that Voltaire ever read Leibniz. Impossible. No time. Simply no time. But since I am not an optimist myself, Voltaire is on my side, and reading this book, it split my sides and I came out with a better understanding of the nonsense our fellow humans (with the possible exception of some, like Leibniz) daily bombard us with. Voltaire's story of Candide, kicked out of his paradisiacal feudal castle and traveling round the world trying to stay clear of threats, survive, and realize his dreams, experiencing and witnessing the most horrific human acts of egoism and flagrant conscious neglect of the interests of others, means to make us aware of the limits to moralities of any brand of religion or rational consideration set by the hard empirical facts of how man actually is: acting on stunning egoism, satisfying his primitive urges while trampling his fellow human beings. There's nothing we can do beyond the limits of that reality, which is so sorry that when we have the courage to face it, Candide means to show, we can not help laughing and crying at the same time. Let us face it! And see only afterwards, based on the knowledge acquired, what is left for us to do.

On his Journey Through The World, young Candide experiences unspeakable sufferings, and hears of even worse from others. Fortunately Voltaire describes them in what we now would call "cartoon"-style so as to make us laugh rather than cry: Candide gets tortured up to mutilation as an involuntary army recruit, is forced to kill to save his life and see others dying undeserved. Fortunately many of those others return in the story to tell they were not so totally dead after all, and were happy enough to get themselves together again and continue their suffering and their annoying of others, the latter in such a way that Candide even has to threaten one of them to "kill him again". No reason for optimism, we are led to conclude. But the trained philosopher observes that Voltaire's optimism is ill defined. When a sailor approaches Lisbon, a city just collapsed in an earth quake, whistles through his teeth and says: "Here we will be able to make quite some earnings!", the man is right to have his optimism, but at the expense of the Lisboan's. When a monk steals the money Cunegonda managed to steal from the Lisboan Jew whose involuntary lover she was, when Dutch sailing merchant Vanderdendur agrees to take Candide to Europe with the vast fortune he was given in Eldorado, decides quickly to sail off with the precious cargo before Candide can board, and then on the Atlantic gets robbed on his turn by pirates, optimism passes from one to the other and so on. Would not Leibniz say that our best of possible worlds is fueled by a constant flow of desirabilities from one to the other, where there is a neatly pre-established law of conservation of optimism? OK, I feel I go too far, but Voltaire's story, believe me, tempts the reader to retaliate joke with joke.

Voltaire

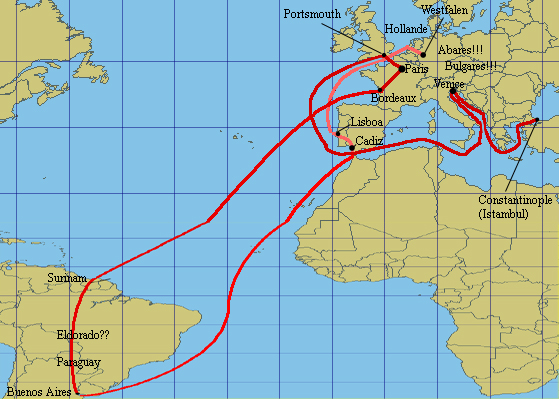

Reader! Enjoy Voltaire's Candide. His trip is thus:

Candides journey through the world (light to dark red line) [Open in seperate window]

Candides Journey Through The World

The original sin: young Candide is kicked out of his foster-father baron's Westphalia castle for touching his daughter. He gets snatched by "Bulgarian" army recruiters for war against "Avares" (satire of massacres of the Seven Years War - Great Britain, Prussia against France, Russia, Austria, Sweden and Saxony - carefully avoiding identification of any of the parties with the savage "Bulgars" and "Avars")

Holland: satire of fundamentalist Calvinist anti-papism, Candide rescued by Jacques the Anabaptist, meets again his German castle teacher Pangloss, half rotten away by venereal disease. The baron's entire family reported killed by Bulgarians

On the sea to Lisbon: Anabaptist Jacques killed by a sailor he just saved.

Lisbon: devastating earthquake (really occurred at the time), Candide and Pangloss killed by inquisition, Candide survives, meets Cunegonda, now involuntary lover of two rivals who settled by dividing the weekdays, Candide has to save himself by killing one of them, a head of inquisition. Candide and Cunegonda flee with the rivals' money, but that money unfortunately gets stolen again by Franciscan monk.

To Cadiz, then Buenos Aires: Candide and Cunegonda separate, due to Portugueze murder arrest warrant, Candide to Paraguay where Jesuit fathers run the state and are at war with Spain (historically accurate). Cunegonda's brother turns out to have survived the Bulgarians too, he is now a high ranking Jesuit military officer, threatens to kill Candide for his ambition to marry his sister, but Candide sword is faster: he kills the brother

Candide arrested and prepared for being eaten by primitive Indians, but released and honoured after they hear he has killed a Jesuit.

Candide finds Eldorado, where he is very welcome, the food is perfect, there are no worries, and the roads are paved with gold and diamonds. After a few weeks he gets bored, decides he "does no longer want to be happy". Departs with a immense fortune given for the road.

In Suriname: Candide agrees to join Dutch sailing merchant Vanderdendur back to Europe. Between the loading of the cargo and the arrival of its owner, Vanderdendur quickly sails off only to be totally robbed at sea by pirates.

But Candide reaches Paris: a boring section where Voltaire ridicules his Parisian critics.

Through Dieppe to Portsmouth, where Candide witnesses the execution of an excellent English admiral whose crime was loosing a battle (actually a recent headline maker of the time). Candide heads for Venice where he dines with six fellow cabaret-dwellers, who all turn out to be deposed kings (V. took all six from actual historical cases). Their stories.

Finally he approaches Istanbul, snatches Pangloss and Cunegonda's brother, who both miraculously survived their predicament, from a galley by bailing them out with his last Eldorado diamonds, as well as Cunegonda whom he finds a slave-household worker in town, retires on a farm with all surviving protagonists and opts for an inward focused life of agriculture and simple small community survival. Candide, thus far total victim of the dangers threatening him, surprise, wonder, and love of Cunegonda, finally finds himself lapsing into words of wisdom: "One should cultivate one's garden".

The garden.

If I would have had Voltaire's talents and written Candide, I would, at the last page, have them all enslaved in the Turkish galleys, mutiny, take over the ship and be killed in an Aegean storm. It would have saved me of the ambiguities Voltaire introduced by letting them survive together as an inward focused self-providing gardening community near Istanbul. The "garden" comes in as a deus ex machina. What made Voltaire do it? No doubt it makes Candide more attractive, because the general public, where the story was a big success, is not buying books and spending reading time to loose its cherished optimism. And except for those preparing for suicide, everyone seems to have a "garden" to have something at hand, to survive, and to repress awareness of the human predicament. Most people's "garden"s consists of a breeding partner, children and a system of personal material supply like an enterprise, business, profession or career to promote, which may be a farm or a workshop or, as Voltaire is not tired to illustrate: theft, robbery, the bar, slave trade&employment, inquisition, prostitution and what not. In fact, Voltaire showed other people's "gardens" all the time until he arrived at the one set up by Candide and his entourage near Istanbul! Is the last one, as Voltaire clearly wants to suggest, the best? Why? Would the world be better if "we all", with our our backs to the rest of humanity, lapsed back in the self supply of small scale agriculture? That thought exists here and there and and has been tried every now and then since. But would that literal interpretation make a resounding sales success followed by eternal fame for a short story by a controversial playwright? One could believe this if the model of Candide's garden would, after its publication, have become prominent among the many literary models used to forge all small community Utopias. But in the small circles of utopians endeavouring practical implementation Voltaire's garden has not proved its mettle. Instead, Candide's garden has widely been taken abstractly, figurative, and no doubt so by his own design. Thus, on the last page of Candide, Voltaire deliberately gave his readers a way out of the corner he had driven them in on all previous ones, making his message acceptable even to those whose life closely resembles one or more of the many persons who, during the book, by their flatly and openly inconsiderate acts threatened wealth and life of Candide and his fellow itinerants. After the reader's highly amusing roller coaster ride he gets reassuringly dropped exactly where he boarded.

| Greetings Home |

PHiLES home PHiLES home

|