PHiLES home

PHiLES home

| Lingeblog Home |

| Previous |

| Next |

PHiLES home PHiLES home

|

Thucydides

The rise and fall of the

Athenian empire

This is a summary of the History of the Peloponnesian War, by Thucydides, written in the years around -400.

The Peloponnesian war, lasting 28 years, from -431 to -404, was fought largely between Greek tribes only. Since the start of Renaissance seven hundred years ago, this period of Greece is revered by the Western scholarship and judged the origin of Western civilization. It was the period of the philosophers Socrates and Plato, playwright Sophocles and Aristophanes, the politicians Pericles, generals Alcibiades and Xenophon, and Thucydides, an exiled Athenian general, author of the history of the war, the book we deal with here. Most of these Athenians knew each each other in person.

At the time the war started, the older generations could still remember how all Greeks had fought together to defend themselves against the border armies of the enormous Persian empire. This war had united the Greeks and had forced them to acquire the war skills needed to prevail, notably marine warfare: the Persian war had forced the Greeks to raise the level of their shipping techniques to the standards of the enemy, who got theirs from the Phoenician sea traders residing in what now is called Lebanon.

This improvement in war technology had left a disparity in the Greek world when the Persians retired: sea side towns gained a dominance due to having profited more of the improved seafaring skill in trade and military operations. Among them Athens took the lead in shipbuilding and overseas trade, boosting a class of rich traders in town first matching, then overtaking the rich land owners in local power.

Thus a divide grew between sea trade towns, typically democracies (a recent invention, see below), not so much dependent on their local crops since able to buy and transport them from far, and landlocked towns with elites chiefly consisting of rich land owners, typically run as oligarchies, who where more dependent on their own crop production and thus dependent for their military safety on land armies, no so much on navy. This divide had a sharper edge because it largely coincided with an ethnic divide among the Greeks, the Dorians usually being land oriented, the Ionians at the sea sides and on the Islands.

Despite the ethnic divide, there was a deep sense of togetherness: most gods and sacred places were considered shared among all, and religious rituals and games (of which the Olympic games were only one of many) were attended by all, and held, under sacred armistice, between all warring parties.

The Greeks typically lived in towns. These should be large enough to allow successful common defense (mainly against other Greeks). At the time, a well built town wall would allow its inhabitants to successfully keep out an armed company many times larger than the defense - until, of course, food would run out. On the other side, a town should be not be too big: then a too large agricultural area around town would be needed to feed everybody, and crops had to be carried in from too far.

A decent town's adult male inhabitants, let me take the 10,000 as a normal number, would roughly consist of some 3000 free citizens, of which 200 rich, and the rest would be slaves, doing the work on the land and menial labour, crafts included. Slaves usually were people captured after defeat (also in inter-Greek wars) and unconditional surrender in a war (mainly women and children, since under unconditional surrender, men would normally get killed) or their descendants.

In oligarchies, the rich had a system of government by consensus, every town another one with its own traditions and intricacies. In democracies, a recent invention, the free men ("citizens") would vote on crucial matters in plenary meetings. In both systems weapons usually were only worn by free men only, who formed the army, though there were exceptions, like the "Helot" slave soldiers of Sparta.

In both types of towns, slaves, think of typically some 70% of the population, were private property of free men and had no political rights. Women had a decidedly background role. In Thucydides' entire work one hears of men only, except when captured women are sold as slaves and on one curious occasion, where brilliant Athenian general Alcibiades has an affair with the wife of the Spartan king Agis - which has some marked effects in some junctures of the war.

After the Persians decided to cease military action in Greece the Athenians, whose town was destroyed and who were left with not much more than their army hardware, rebuilt and walled their city in no time and founded a league of seafaring towns, the Delian league, that soon comprised by far most towns on all islands and coasts of the Aegean. It started policing the sea to make transport safe against pirates and other attackers and so created a maritime trade zone that developed at astonishing speed.

Sea side towns would normally lie a few kilometers inland on a defendable height to be safe from ship attacks during war or piracy (there was little difference between these two). After acquiring so much more security at sea, fortified port towns got built, often, like in Athens, connected by long double walls to the old town. Now able to massively import crops by sea, its size was no longer restricted by its surrounding land and it grew to about 4 times the size of an average Greek town.

Many Greek towns allied voluntarily with Athens to provide ships, soldiers and money, others did so out of fear, again others simply got forced, thus becoming subjects. The league grew, the power of Athens over its decision making as well, and tributes in fact often became seen as tributes to leader Athens. Thus, the first democracy in the world started to crypto-dictatorially rule an empire with their fellow Greeks as subjects. The "agreement" to enter the league usually got cast in the most amicable and democratic of words. Athens ruled the sea and its coasts in the Aegean, and part of what is now the Greek side of the Adriatic.

Greek cities, colonies of home cities like Athens, Corinth, Thebes, Sparta, Argos etc. at the time were already scattered all over the North Mediterranean (up to Marseille and even Northern Spain in the West, and up to the far East coast of the Black sea coast, but most of the ones beyond Byzantium Eastward, and over the Adriatic Westward felt themselves too far to be bothered by the Athenian expansion. But in the nearer vicinity, where Athens had not yet made "friends" already, it was in threat of doing so soon, to the growing worries of the others under the leadership of Sparta, now a third of the size of Athens.

So one would normally expect a Ionian city to be sea oriented and be run as a democracy, while Dorian cities tended to be land locked, land oriented, dominated by a land owner elite that would run it as an oligarchy. But there were marked exceptions: Corinth was Dorian and consistently oligarchic and anti-Athens, often more so than Sparta, but decidedly sea faring. And there were games with the labels too: a "democratic" movement on Samos, for instance, turned "oligarchic" when they discovered this boosted their position [details below]. And in the fire of the war to come even the Atticans could be addressed as "Ionic".

The fast rise of this Athenian empire forced other Greek cities, fearing for their freedom, to unite, and that is where Thucydides starts to report his history season by season.

The pre-war chess board (only mayor towns indicated).

Spartan general Brasidas hasted to establish a

Spartan presence in the North Aegean

There's an incident build-up but sooner or later it should have happened anyway: the Spartan alliance acquires coherence. Two years before what Thucydides labels the "start" of Peloponnesian war (-431),

Before the beginning of the war Dorian Epidamnus [map] banned its nobles in a democratic coup, in reaction to which neighbouring Dorian Corcyra interfered. Freshly "democratic" Epidamnus went to oligarchic Corinth for help and got it! [map]). This Corinthian help to a democratic coup was inspired by the rivalry between Corcyra and Corinth at sea. It made Corcya, a long standing neutral between the Spartan and Athenian alliances, furious, and ready to call in the democratic Athenians who indeed decide to engage and help them, after waiting long enough, at some distance, to be sure they were on their way to a sure defeat, to win the sea battle of Sybota.

These were curious cross over alliances: Athens, materially helping to quell a democratic rising supported by oligarchic Corinth! Athens seems to have regarded this as just slight collateral damage of forging a bond with strategically useful Corcyra - having Corinth as their common enemy and owning the second biggest fleet after Athens. Corcyra's entering in the game brought the fear and heat to ignite the war: a few days after the battle, Corinthian envoys were out in all directions, Sparta included.

... open in separate window ...

Year 1 of the war (-431). Of course we start burning each others' crops. The damage to Athens is limited because of their sea import capacity, that of Sparta because the Athenians have to restrict themselves to burning coastal areas. Everywhere in the Sparta alliance it is realized that shipbuilding and naval skills should be boosted if they ever are to be a match to Athens, which for the moment, everybody knows, they are not.

The Athenian alliance would have had little reason to worry were it not that Athens got hit by a devastating plague epidemic, and another one a few years later. They killed a substantial part of the town's population. 50% should not be far off the mark (which including women, children and slaves would be well over 100,000). Unburied corpses rotting on the streets. The second epidemic killed, Thucydides claims, 4400 heavy infantry and 300 cavalry. But even in such circumstances a walled city seems unconquerable (though fear for the disease might have deterred Peloponnesian alliance as well).

The plague did not tip the balance in the war. In the seventh year of the war the Athenians, despite some setbacks here and there still had the initiative. In an accidental spinoff of another operation Athenian navy general Demosthenes uses a forced bad weather stay at Pylos (straight West of Sparta, uninhabited at the time), seeing the landscape suitable, to build a fortified harbour. A Spartan army appears. Part of it occupies a 5 km island shielding the harbour bay. Demosthenes manages to isolate them causing, after protracted siege, the unique event of 120 surviving Spartans, no doubt of the most influential families, not fighting to death but surrendering and being taken to Athens.

The Pylos disaster changes Sparta's war strategy to acquiring the leverage for a truce to have them released. But they are still far from such a position. When a year later the Athenians take the rather big island of Cythera, commanding the bay of Sparta, they meet no resistance.

Spartan general Brasidas goes, after having participated in some operations in and around Attica, North, invited by king Perdiccas of Macedonia. All sea towns in the North are subjects of the Delian League, surely not all happy with that and ready to rebel if Brasidas could be the occasion arising. He goes in the Spartan way: marching. They have to cross Thessalia, sympathetic to Athens, and manages with some difficulties to reach Perdiccas, with whom he can't agree on a common strategy. Largely without Perdiccas' promised military support and money he proceeds to try and "liberate" the sea towns of Chalcidice.

Once in Chalcidice, Brasidas acquires quite some allies by "not speaking badly for a Spartan", our fired and banned former Athenian general Thucydides, at that moment still under contract and near, concedes. Despite the advent of Athenian army and navy, talking and fighting, Brasidas "liberates" quite some Chalcidian cities and turned the naval expertise he finds amongst them against Athens, building ships, manning them, despite little support from Sparta.

War tiredness of all parties leads to negotiations. Brasidas dies in battle, leaving a substantial number of pro-Peloponnese cities in Chalcidice. In the 10th year of the war parties conclude a 30 year truce "of Nicias", the Athenian general who was its chief architect. Athens releases all Spartan prisoners of war including those from Pylos.

This 30 year truce will hold 7 years. It is chiefly unstable because Sparta's allies are dissatisfied with it, some important ones, like Corinth and Argos, even refuse to be part of it. At this point in time Sparta, despite the far away glory of Brasidas, seems on its way down.

In the truce period Athens recovered at an astonishing speed from the war expenditure. This was the result of Athens' overseas trade and its capacity to extort its "allies" and subject cities. Even the recent devastating plague epidemics were overcome, in Athens, by a remarkable rate of human reproduction. Youth abounded.

The vastness of the new echelons of enthusiastic young free citizens, and the impossibility of internally using the results of the enormous wealth - stomachs have their limitations and few pillars in Athens could carry more gold than they did already - made young Alcibiades and others dream of an expedition to Sicily, to challenge from there may be even Cartago (at the time a famous and big city in what is now Tunisia).

After all, you can't all be philosophers, artists, poets or playwrights; all those sons of free citizens less blessed by the muses had nothing to do apart from sports, military training booze and sex. Homosex between married adult men and underage boys, widely accepted all over Antiquity: whoever did not take part in it was seen as strange. Work was done by slaves. The dreamt-of expedition would not be a violation of the truce. Thucydides claims the Athenians were unaware of the size of Sicily. They underestimated it. Under the democratic thundering of Alcibiades the vote, in the 17th year of the war, was for the expedition, to the worries of the experienced generals, like Nicias.

Athens and her "allies" went on a 7150 head 134 ship mission to control Sicily, Alcibiades excited to have been voted general, other Athenian generals less than convinced of the rationality of the entreprise but obeying their government. Even after having been informed of the plans by reliable sources, many able statesmen in Sicily were unwilling to believe the Athenians were really coming. But they came.

Alcibiades, however, was recalled to Athens before the army had reached Sicily. He suspected to be put to death in an unfair trial at home, and fled to Sparta, where he became an adviser of the Spartan league, successful in the effect of his recommendations, but not in winning the trust of all his former enemies there. His affair with the wife of the Spartan king Agis was not of much help either.

The Sicilian expedition, now under the leadership of generals who had been against it, was met with distrust already in South Italy. No one reported to become an ally, they would not be provisioned except for money and outside the town walls.

Once on Sicily, things got grim. The town that had called them in turned out smaller than they had said they were, and the money promised largely failed. Many Sicilian towns had the courage to ally against Athens and not only managed to hold out long enough for help to come, but acquired navy skills on the job as well, and received a Spartan platoon. Battle turned into a siege of Syracuse. But the Athenians failed to isolate it. The defending alliance even got so close to victory that Athens a year later had to send another 73 ship fleet and 5000 head army and an awesome lot of money to save the situation. But at the same time the Spartan allies sent massive help to the other side, adding not only to the manpower and the ships but also to the military expertise of the quickly learning Sicilians.

The double Sicilian expedition ended with the complete destruction of everything Athens had sent. There is severe counting inconsistency here in Thucydides when he mentions that when Nicias and Demosthenes try to withdraw over land, a last sea escape attempt being thought impracticable, they march off with "40,000 men" (where Thucydides' reports of men shipped in add to 12,150). I do not know what accounts for the difference. It could partly be: 1. slaves or oarsmen in the expedition now counted while they were not when arriving, 2. allies and mercenaries who joined in a later stage.

After some days of flight Demosthenes' rear guard surrenders (for life only) with "6000", the rest under Nicias gets massacred, Nicias reports at the enemy, of the surviving part of the Athenian army most got scattered over the island and went in hiding. Of the rest, after been held in a quarry for 70 days, the non Athenians were sold as slaves, the rest taken prisoner of war.

Only a few Athenians managed not to get killed or captured, and could, each after his own private Odyssey, bring the message home, at first without meeting belief.

Few at that moment gave the Athenian empire more than a year. It caused some precipitous rebellion, a first windfall for Athens. The war would end with the fall of Athens but that would take another 9 years and had by no means become unavoidable by the Sicilian disaster.

The point of gravity of the war now moved to the East coast of the Aegean where Miletus, an Athenian subject, formerly Persian, became a target for Peloponnesians paid by Persian satrap Tissaphernes. Some coastal islands there (Chios, Lesbos) rebelled against Athens. Samos became the Athenian navy headquarters. There, the rich had established an oligarchy, which however soon lost its power base to the Athenian army. The Athenian treasury had been almost depleted after Syracus, Athens did vigourously return to shipbuilding and army build up and, despite the internal turmoil, was not in existential threat.

Thucydides' history ends at the end of the 21st year of the war (-411), seven years before the actual surrender of Athens town to Sparta. These seven years form far from a gradual demise of the Athenian empire. Spring -407, the 25th year, Alcibiades is invited back to Athens. For two years he acts as a highly succesful naval general in several great battles, creating total despair among the Peloponnesian military leadership, until in -406 a battle lost gives his enemies at home the chance to let him loose his credit in the hectic, unwise and uninformed democratic debate and decision making in Athens. The sack of Alcibiades and some more of the ablest generals at that point turned, many sides hold, the Athenian military into the lame duck that finally allowed for the mistakes leading to the fall of Athens.

Five years after the war old Socrates was sentenced to leave or take poison in Athens for "spoiling the youth", by with the persecutors meant: Alcibiades, his boyfriend when underage.

We shall never know how solid Thucydides' history is based on reliable evidence. But the variety of facts he adduces and the impression he makes as an author, pointing at both errors and well devised operations on all sides, make it hard to believe he was largely making things up or lightly believed biased judgments received from others.

Reading a summary of Thucydides like this is not good enough. One should read the book, for it is full of observations that easily could grow into the pet theory for some modern academician to ride to fame on. A lot of side remarks thought less significant or even obvious to himself give, to a contemporary reader, totally unexpected clues to understanding the human condition in the classical era. I dealt with some, let me deal with some more.

Some problems of war

It is not easy to determine the right size of army for an operation. It is not the bigger the better, because armies have to eat every day. Big armies have to break up quickly and move faster because they quickly deplete the locally available food stock.

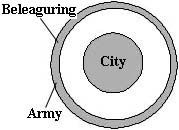

Properly built city walls were insurmountable obstacles for an attacking army at the time. When you want to beleaguer a town that might hold out a year with its food stock inside, you need a small army, just capable of keeping the city closed while feeding itself from locally available sources for a long time. Defenders of a well equipped city with solid walls were virtually invincible except by starving them.

A good method hence is the construction of a double beleaguering wall: you surround the city

with a wall to prevent any outbreak, and another one to prevent being

stormed by an outside army coming to help the city. A double wall like this

could be held by an army small enough to feed itself from the surrounding

country, and held long enough by the small guard for a big army to be sent

for a fast operation of battle against any big army coming to help the city.

A good method hence is the construction of a double beleaguering wall: you surround the city

with a wall to prevent any outbreak, and another one to prevent being

stormed by an outside army coming to help the city. A double wall like this

could be held by an army small enough to feed itself from the surrounding

country, and held long enough by the small guard for a big army to be sent

for a fast operation of battle against any big army coming to help the city.

Surrounding a city with a beleaguering wall was possible even with seafaring cities because most of them were founded at some distance from their sea port, to be better defensible against pirates. In the era of the beleaguering walls, it became attractive to connect city and port, if reasonably close to each other, with long walls. The city could not any more be surrounded by a beleaguering army and could import food from the sea side, unless a naval blockade would be part of the beleaguering, which easily made its costs exceed the expected benefits.

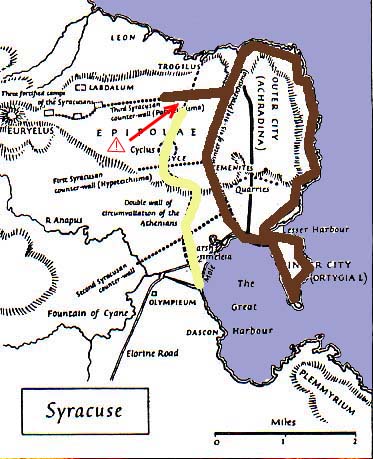

One of the spectacular moments of the defeat of the Athenian beleaguering of Syracuse was when the Syracusians managed to block the finishing of the North end of the Athenian

double beleaguering wall by a counter wall (red arrow left pic, as Thucydides claims, by using the

stones put ready by the Athenians to build their own wall). This made it

impossible to isolate Syracuse at the land side.

One of the spectacular moments of the defeat of the Athenian beleaguering of Syracuse was when the Syracusians managed to block the finishing of the North end of the Athenian

double beleaguering wall by a counter wall (red arrow left pic, as Thucydides claims, by using the

stones put ready by the Athenians to build their own wall). This made it

impossible to isolate Syracuse at the land side.

To work with a really big army, think of 100,000 head, you should be a great leader. Just the marching required subtle steering. If we are to believe Xenophon, who thinks of it as normal, Cyrus' army, some time after the demise of Athens, underway in his own Persia to depose his brother, destroys all he passes. That is not how to do it. Moreover he looses the battle at Babylon and dies.

Again a few years later Alexander the Great did much better: he kept speed in the army to not exhaust the lands it passes. Thus he left communities behind strong enough to maintain themselves and be part of an empire by defending it and paying tributes, not just uninhabited farms like Cyrus did, whose army took most survivors with it as sex slave, servant or soldier.

Running a town

Inside towns parties tended to unite against other parties. In cases of higher tensions, such as war, this coalition-seeking naturally ended where all got united into two parties, each unifying a pretty diverse set of people who often would be ready to oppose each other might the circumstances be different, each of them only inspired to keep the other one in check: the enemy of your enemy is your friend.

Many times the divide resulting is totally erratic and caused by accidental rows in the past, but often one party leans on the wealth of its main members while the other tries to rely on numbers. Then the latter would feel political kinship with the Ionic democratic towns, and the former would tend to ally with the Peloponnesian oligarchies. Hence both sides in the war had their party in many towns, both in their own and in those of the enemy alliance, and where not, something could be done about it.

Inside cities, quite some energy was spent on suing, exiling and murdering members of opposing parties. Quite some beleaguered cities were secretly opened, or in continuous danger to be so, by members of the party considering its interest to be enhanced by the beleaguering enemy. And this also when a town's divide was not so clearly between rich and commons.

The most amusing history on this by Thucydides is that of a "democratic" rebellion, supported by the newly arrived Athenian army and navy on "oligarchic" Samos in the 20th year of the war. Then Athens experiences its short lived oligarchy of the four hundred and the news arrives on Samos. This, combined with a pro-oligarchic stance of Alcibiades (still in Persia but in contact), who hoped such an oligarchy could recall him to Athens, makes the Samiot rebellion decide to change flag, and, now calling themselves "oligarchic" rebellion, turn and fall upon the commons!

After this ring of rebels has come out in their new posture, Alcibiades finds out that the new Athenian 400 oligarchy are not his people and reinvents himself as a democrat. Moreover, the oligarchy in Athens seems fragile and raises nothing but indignation in the Athenian army on Samos. The real Samos oligarchs, that is: the real rich, try to seize power together with their overly flexible fresh ring of new fake oligarchs and are defeated by the Athenian soldiers. Thucydides: [the Samiots] "lived together under a democratic government for the future".

Knowledge and craft

To decide for one war-operation is not like deciding for a general war, like the one Thucydides reports. To form proper expectations of a war that may last for many years is hard due to matters of good and bad luck in big battles, but in a large part due the quick and unpredictable spread of decisive knowledge and ideas of military technique. In militarily targeted cities, the prospect of all males being killed and women and children being sold off in slavery did dramatically stimulate brain and senses. Thus during the Peloponnesian war, landlocked Sparta produced a generation of expert naval generals, and Syracusians learning from every naval operation against the attacking Athenians, became considered as Greece's top naval warriors.

Thucydides mentions a host of new war techniques and inventions: Corinth started to build triremes reinforced at the bow, able to sink Athenian ships by frontal ramming (previously, ship ramming was thought to be successful only if coming in at the side). After loosing its existing generation of ships, of course, the Athenians reinforced the bows too, but now they were catching up instead of leading. Syracuse hammered hardwood poles in the sea bottom before its city walls, with sharp peaks below the surface. A interesting diver's war ensued between defenders and attackers of these poles, with little profit for the Athenians. Quite some new engines to set walls of beleaguered towns on fire. It is interesting to the contemporary observer that craftsmen involved usually were slaves, so the slave communities had a value as pools of know how. Also, not rarely, private teachers of the wealthy youth were slaves.

| Lingeblog Home |

| Previous |

| Next |

PHiLES home PHiLES home

|