PHiLES home

PHiLES home

| Lingeblog Home |

| Previous |

| Next |

PHiLES home PHiLES home

|

Created 14-08-29

Last edited

20-12-27

... brilliantly

phrased to amuse the very few early converts to modernity,

decisively unsuitable to win anybody over to it

...

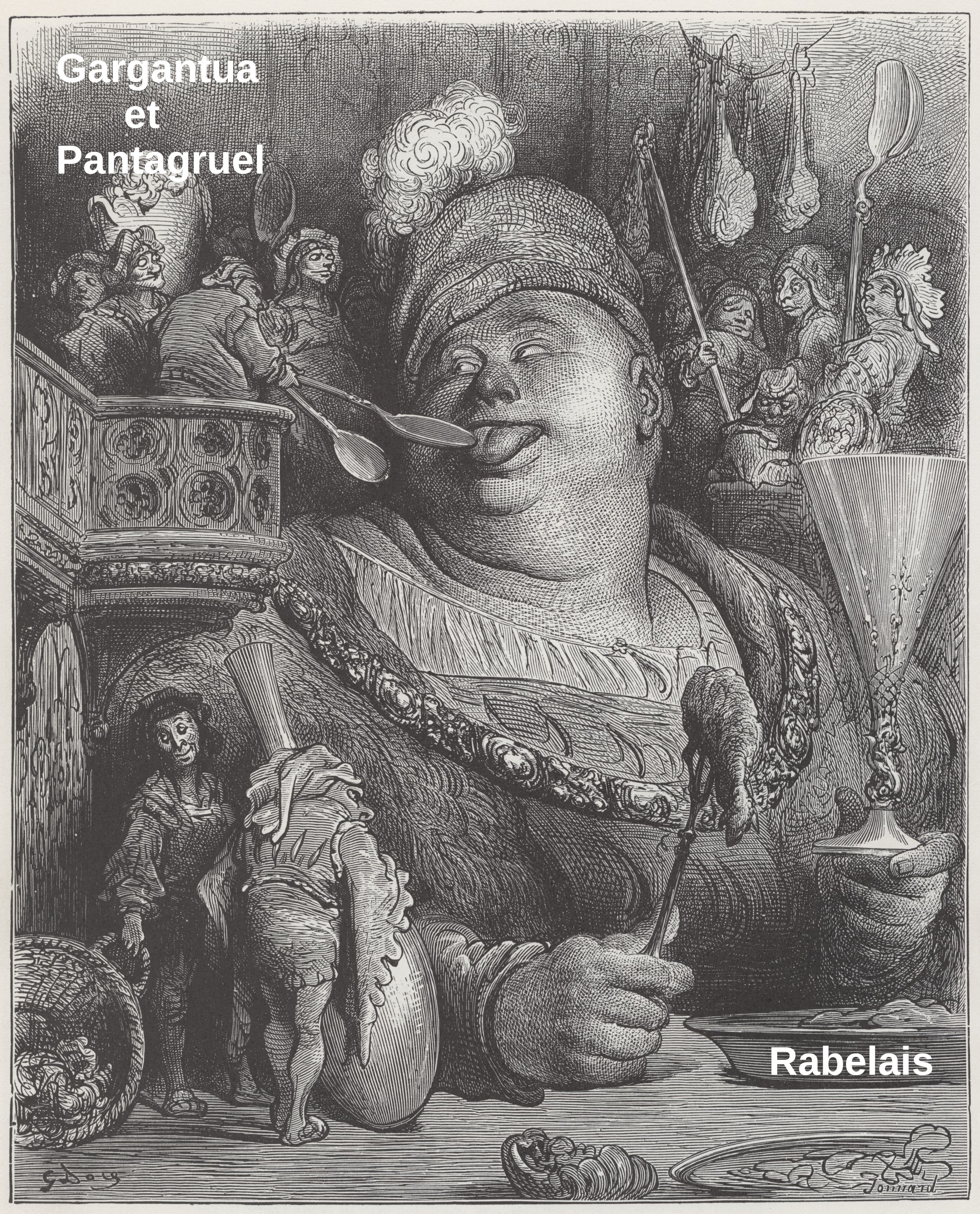

Gargantua and Pantagruel

Francois Rabelais

Rabelais wrote, five hundred years ago, purely for pleasure, he was mainly a medical doctor, five books of parody. What first catches the eye is that in a remarkable fit of genius he started at once with Book 2, about giant king Pantagruel, son of Gargantua. Gargantua was the hero of many existing stories of romantic heroism, quite suitable, he must have thought, to have it lapsed into something resembling, at least related to, a comic book, one where the pictures are drawn in words.

Rabelais' project resembles that of the early 17th century Don Quichote, but that would be more than a century later. I dare say Rabelais wrote for an audience more intelligent but similarly skeptical towards everyone ambitious to conquering the world, loudly proclaiming the truth, scholarly referring and predicting, ready to assume the defense of glorious cases, to acting as God's postilion, telling us what our youth needs, and similar, of which we only mentioned the least, all these vain endeavours we see pursued all around us, accompanied with the pitiful use of all those dull and worn tricks such as the reading and quotation of authoritative books, the collection of pompous arguments, astronomical observations, the interpretation of oracles, prayer, articles of law, the colour of liberated intestines, jurisprudence, mathematics, the horse, the sword, to mention only some not even at the top of the full list that brevity does not permit us to present here in its depressing entirety.

The book is brilliantly ridiculing the aggression-called-heroism, book-derived wisdoms and superstitions of the lifestyle of late Middle Age tradition to the forum of early converts to modernity of Rabelais' times, but decisively unsuitable to win anybody over to it, yes, even just creating havoc and fury in conservative circles.

But!

After finishing Book II, the author, realizing the existing confusing myth formation concerning Pantagruel's father Gargantua, at once, and adæquately so, deemed desirable and appropriate the scrupulous recording of the genuine, essential and definitive version of that old king's life, words, and deeds, and the important things as well. And call it: ...

Book I: Birth and reign of Pantagruel's father Gargantua

Finally, after all myths, propaganda, commercially inspired phantasy and worse, we hear a most trustworthy account of the birth of the giant Gargantua: this took place at a rather unhappy moment, for his mother had just swallowed a serious overload of tripe. Her ensuing prolific diarrhea did NOT!, as has widely been claimed, simply make baby Gargantua lose hold an flush out. The truth is that his mother's team of midwives administered a powerful herbal stopper, as a result of which Gargantua saw his exit road blocked and could do nothing but escape from his mother's ear. Her left ear.

Now you hear it from an expert medical doctor. In person. First hand.

What follows is a slightly confusing period indeed of experiment with a host of different pædagogolologies applied to the newborn, during which the giant toddler proves mathematically to his father that the optimal way to wipe your ass is by employing a goose-neck. Even Paris gets frequented to embellish the education. We must comment here that our esteemed author's detailed account of Paris learning would give him some quite unnecessary, unjust but nevertheless nasty problems in later life.

But no more time for fun in Paris: at home war breaks out. The parody of pedagogy, scholarship and education is replaced with that of the rhetoric of the conqueror ("Picrocole"), and, not to forget, the unjustly attacked: Gargantua's infinitely wise and morally sound father, king Grandgousier, who, it goes without saying, never wished anything else than live in peace and friendship with his ill tempered neighbour and in his excessive goodness attempts to avoid bloodshed by impeccable rhetoric and gifts, but, seeing all that founder, does not hesitate to swiftly mobilize the neatly organized, integer and brave army that he always held available to, God willing, back up his foreign policy whenever appropriate.

These eminent battalions of course beat Picrocole's armed gangs of undisciplined plunderers in a blink of the eye, so Rabelais has to engage in several slow motion repeats to make sure no more belief will ever more be attached to that pitiful host of previous sloppy accounts of this battle that unfortunately are still occasionally sold on the market for no small prices at all. Are?, I mean were, in Rabelais' time, for our hero author wiped them out as Grandgousier did Picrocole: to my knowledge, no copies have survived, and if I were wrong, that would be a shame indeed.

But this is only the beginning of the book's sizeable series of wars and travel that would have stuck Homer's eyes out had he not been blind already.

After an admirable speech to his vanquished and disarmed enemy, about another war in which the winner forgave the looser and sent him home with presents, which was told to have boosted goodwill to such a degree that for years voluntary contributions were substantially higher than a forced tribute would have yielded, Grandgousier pays their journey home, including the patrolling costs needed to protect them against the peasants they looted.

(Some minor issues: Grandgousier keeps hostage the entire nobility of fugitive Picrocole, adorns their cities with garrisons and sends some of his courtiers to enhance the efficiency of government and taxation)

Rabelais started as a monk and kept the status all his life, despite all his travelling and working as a medical doctor and reservations of the odd high congregation officer lacking the brains to appreciate the world literature he produced.

It must have been a feat of his utmost discipline not to have made any joke about convents and monks up to this point and his utter relief when in the earliest stage of the run up to the war just described, Rabelais finds Picrocole's undisciplined gangs already attack a convent!

Needless to say, the convent is bravely defended, by prayer, but one monk takes the huge cross from the wall and starts crushing enemy skulls with it, in such a way as to not damage the precious convent's wine grape plants. On his way to his ultra short flash war Grandgousier meets this brother Jean, a towering figure in the rest of the book, who immediately, due to his acts of fearlessness and fits of ingenuity, which are well beyond the scope of this tight synopsis, starts rising in the ranks of Grandgousier's army. Let me clarify: mistakes, by a monk, like at one time, not used to metal armour, keep hanging at an oak branch refusing to break, with horse and all, and, second, to be taken hostage for an hour or so, that's all well within Perfectness' margin of error.

Now, the war done, as a distinguished reward for his war acts, Grandgousier gives this brother Jean the funding for a convent in his very own design, which Jean decides to baptize Thélème.

Stuffed with 2.700.831 gold Agnus Dei crowns, this on top of an annual building cost defrayment of 1.669.000 sun crowns, and the very same amount stamped with the sign of the Pleiads, as long as the construction would take, all apart from the basic exploitation budget of 2.369.000 Rose Nobles, brother Jean's ingenuity produces a brilliant plan for an upside-down convent.

It was planned to easily outdo Marco Polo's description of the palace of the great Khan in Beijing, let alone the actual palace that Polo visited: a gigantic six-angle with six towers, enclosing an immense park full of delicious hunting game. Monks, male and female, integrated, mixed in what was going to be no less than a city, would have acceptance and entry without any oath whatsoever, be professionally dressed by able craftsmen in expensive attire, and be allowed to leave any time, at their personal discretion. There would be clocks nor bells, schedules for day, week, month nor year. Religious staff would be stimulated to dedicate itself to any urges or ideas surfacing at whatever moment. Brother Jean expected this to result in mutual education in the arts and sciences, and collectively keeping out all dirty pock-marked monks of alien orders, as well as restricted book worms and most notably lawyers, all under the Motto of the Order: Do What You Want.

Immediately a location was earmarked and the digging began, which in no time resulted in the archeological find of a bronze plate with a confused story about discord, strife and some kind of deluge, from which only the best would resurface. Little giant Gargantua, mesmerized by the project and always to be found at the building site, felt the plate was intimately related to the Holy Truth, but brother Jean begged to differ, seeing in it a subtle allegorical description of the game of tennis. To our dismay, slightly mitigated by seeing several more books before us, this already marks the End of Book I

Book II: Birth and education of Pantagruel

... which was the first book written in the first place. Of course it starts, as ought, with the amazing way Gargantua's son Pantagruel was born. No need to say his education provides for a decent update of the new levels of debility and silliness that contemporary scholarship, especially its Paris establishment, has managed to achieve since Gargantua was being educated, then, naturally, we suffer a cowardly attack by a neighbouring king, go on a decent, morally impeccable and technically flawless retaliation, in which we chase the despicable culprit and take his land.

But I mention this is only by way of preface and overview of Rabelais' invaluable material of detail that I am so blessed to be in the position to present below.

Pantagruel's birth is promising indeed: when his mother first feels things pressing from within, a retinue of 68 mule drivers appears, their animals heavily burdened with salt, then nine dromedaries loaded with ham and smoked ox tongue, seven camels carrying salted eel and twenty four loads of garlic and onion. When Pantagruel finally appears in person, his mother is happy to die.

Then Pantagruel's education: meanwhile, since his father Gargantua was sent for education to Paris, the local community of scholars had been active indeed, to reach new and awesome peaks of nonsense.

But first, on the way to Paris, Pantagruel passes Orléans, where the university has been thoroughly modernized: the campus got stuffed with tennis courts, tennis now being the only subject taught.

When, after some days, Pantagruel was the school's tennis champion, he continued his journey to Paris, finding a book treasury that would make his father stand in awe, in the famous library of Saint Victor. I mention some of the most eminent works: The Art of Civilized Farting in Company, How to Eat Ham (3 Vols.), Recent Contributions the Theory of How to Serve Mustard After the Meal (14 Vols. collected by M. Vaurillon), but forgive me to refer to the original work for the 14 page list of - only the best! - books in Saint Victor.

His father's next letter reads: "I am jealous of your opportunities, for my times were no so conducive to education as they are today."

Pantagruel was a clear talent in study and scholarship. Not long after his arrival in Paris he got invited by Paris' highest court to arbitrage in in de long standing, much discussed and complicated judicial procedure of Mr. Kissmyass against Mr. Failsucker.

The first thing he did was to order the burning of the entire file, which was a nice boost for the city of Paris for it was a cold winter indeed.

Then, in the agreeable temperature produced by that huge fire, he called in the disagreeing parties, bare handed as they now were, and heard each of them in the presence of the other. An eloquent but entirely incomprehensible indictment was answered by a defense easily matching in eloquence. But Pantagruel's sentence was the most impressive and incomprehensible and caused the absolutely unique historical event of satisfying both parties. They all parted as friends. This definitively established Pantagruel's reputation in Paris.

Around the time of these memorable events, Pantagruel first met what I consider the main, nay, the only character of the book, Panurge. While other protagonists of the book do not rise far above some stereotype, this Panurge, it quickly gets clear, takes to the sky. Rabelais leaves little undone: after being occupied presenting him to the reader by general description and anecdote for many pages, we encounter a header: "Panurge's character and qualities", as if we were only beginning to deal with him.

And Panurge's character and qualities can not be denied: a well built and elegant appearance, though unfortunately so totally and completely covered with repulsive wounds and scars that he always seems to have just escaped from the dogs. When Pantagruel first meets him and asks for his name, family line and origin, Panurge insists in twelve foreign languages that he really is too hungry to answer in decent French, but after elaborate feeding and alco-hydrating he relates, in perfect French, his mother tongue, he now concedes, that he, after being spitted and put on the fire by the Turks, by a stroke of extreme luck succeeded, using a cunning ruse that put entire Istanbul on fire, to escape, still smelling of the ham and marinade employed to that despicable attempt to have him roasted, persecuted by more than six, no, more than thirteen hundred and eleven hungry dogs fleeing the fire as well.

Panurge's craft and wisdom astonish Pantagruel, as well as the author, who now turns out not to be Rabelais in person but a certain Alcofibras. The awe reaches a temporary peak when Panurge proves from the classical principles of pure logic that Paris could best be defended by a huge wall of cunts and pricks. Nor does he shy away, a full section gets devoted to it, from a full specification of the technical details of the construction process of such a wall. Let me add that at this stage of the book we have not even reached the aforementioned header: "Panurge's character and qualities". I, for me, would not need more words, I am fully convinced.

But Rabelais (or his ghost writer Alcofibras) is unstoppable and devotes a separate chapter to Panurge's qualities as a villain, swindler, drinker, vagabond, always broke but endowed with an ample arsenal box of tricks, methods, ways, and stratagems to solve that so frequently recurring tiny problem, all that aside of a huge lot of more schoolboyish schemes to spread discomfort of a nature more entertaining than profitable.

Rabelais is clearly keen to leave no items of Panurge's trick boxes unmentioned, nor the ones he adds as soon as, during the book's events, the opportunity presents itself. For example, Panurge instantly employs his fresh friendship with Pantagruel to seek his girlfriends higher on the social ladder and approaches youthful married noble ladies in the following style: "Madam, it would benefit the entire nation, for you yourself it would be an unforgettable enjoyment, and finally, for me it is an absolute and inescapable necessity that I serve and fertilize you." After such and similar words immediately - after all, his kingly friendship had made his money stocks inexhaustible - questioning the lady concerning what presents she would prefer to receive.

When one of the ladies once kept refusing, he rubbed her precious coat in, unnoticed, in church, with the minced cunt of a bitch at heat, after which she barely reached home with all male dogs of Paris in her pursuit, in their turn followed by the rest of of the population. It should now be clear to everyone that, though it firmly looks like Panurge never was in Istanbul, he definitely has a character.

Highest time for a letter from king father Gargantua to his son Pantagruel collecting laurels and excellent friends in Paris. Anarch, king of the Dipsodes has debased himself by embarking on a cowardly invasion of one of Gargantua's far off lands: Utopia. It seems to be located somewhere behind Cape the Good Hope.

Off goes Pantagruel. Panurge immediately assumes the status of a key Officer of General Staff, among other intimate friends and heroes we shall meet later, like Epistemon, and, of course, brother Jean. The struggle is entertaining as Ilias, except for there being no doubt any moment about who is going to win.

For a start, Panurge successfully applies his experimental LUI (Lethal Urine Inundation). It consists of administering powerful herbs, medicine and shiploads of White Anjou to Pantagruel, who then pisses over the enemy troops until they are thoroughly drowned. But there is an enemy elite battalion of giants that manages to keep its head above the urine, so a duel between Pantagruel and Anarch is needed to settle the disagreement. Choice of weapons will be free, so Pantagruel opts for sticking an entire ship, masts and all, under his belt and reports ready. The fight is short indeed.

Meanwhile, due to a minor lapse of military attention, general staff member Epistemon's head is grounded, severed from his body, but Panurge takes his sewing set to attach it again, which allows Epistemon to report his short visit to heaven and hell. The Great of human history appear to have quite ordinary jobs there (let me just mention, by way of interesting addition to Dante's report, he found Caesar caulking ships).

Time to advance to the enemy heartland, in torrential rain, but all Pantagruel needs to do to keep his army dry is stick his tongue firmly out. Author Alcofibras manages to climb up and enter Pantagruel's mouth, sporting large spaces of arable land, farms, villages and cities. When he comes out, Pantagruel can't wait to hear his travel report. Alcofibras hears it is now six months later, and notes with satisfaction that during his mouth voyage the Dipsodes, with God's help, have been thoroughly subdued.

As a reward for his brave explorations Alcofibras is given the castle of Salmiguondin. End of Book II.

I you have no character, you are perfectly able to, just to mention the least, commit murder, conquer countries, collect huge capitals, be reprinted, reach the encyclopediæ and history books, acquire prizes, awards and children, become a giant of human history, and even die, but if you dispose of one, like Panurge, something interesting could possibly happen. And this is exactly what provides us, you and me, that is, the few, no, only, if I come to think about it properly, endangered earthly creatures blessed with the rare ability to properly enjoy reading, with the last three books of Rabelais' Pantagruel.

The last time we see Panurge in total satisfaction with himself is when ...

Book III Metamorphosis of Panurge

... he gets scorned, by Pantagruel, albeit in all friendship, about his debts.

At that crucial moment of the book, Panurge not only has become friend and parasite for life of Pantagruel but his vassal as well: he got the Dipsodic Salmiguondin castle, that earlier was promised to Alcofibras, the acting author of book II. Rabelais feels no need to explain this. At Salmiguondin, Panurge had worked himself in debt faster and deeper than ever, with a merciless rhythm of parties stuffed with pleasures of the flesh of all imaginable - and even some unimaginable - kinds.

As I said, he is still in good spirits and with ease keeps the upper hand under the attempts of Pantagruel to admonish him about his debts. It is here that he launches his famous theory, ever since cherished and applied by all wise men, about the value of debt: making debts satisfies the four cardinal virtues commutative justice, distributive justice, power and moderation, Panurge explains with a plethora of arguments and examples taken from the High Court of Paris, Hippocrates, Plato, Cicero, Vergilius' Testilis, the Celtic druids, Xenocrates, Hesiodus, Metrodorus, Saturnus, Jupiter, the Stoics, the Titans, the Aloides, the Gigants, Lucifer, the mysteries of Dou, Belief, Hope, Charity, Lycaon, Bellopheron, Nebucadnessar, Aesop's Apology, to name but a few.

Debts, Panurge argues, form a ring of safety around us: the creditor wants his money returned, hence will always be friendly, never speak evil, help you find other creditors, protect you whenever you get threatened, and so on et cæt.

Pantagruel, frustrated by his inability to find even the smallest of holes in Panurge's defense, retaliates non-verbally by paying all Panurge's debts at once.

The facts immediately corroborate Panurge's theory. He will never be the same.

Shortly after, Panurge appears before Pantagruel with a precious ring in his right earlobe. Its stone swapped for a flea ("getting a flea in your ear" can mean: being reprimanded), wrapped from head to toe in a five meter rough brown piece of cloth, a cap on his head with a pair of spectacles dangling down at a rope.

His so familiar knickerbocker is gone, as well is his most characteristic piece of clothing, his cod piece, a protection of the full and total entirety of penis and scrotum, the full and total entirety I indeed said. Panurge was blessed with a sizeable cod piece collection of all types of cloth, tissue and leather, piece by piece construed after prolonged fundamental and minute discussions with his team of tailors, and usually reaching the ground [images].

Panurge clarifies himself: he wants to marry but needs advise from his best friend.

Pantagruel smells a rat and looks disinterested, If Panurge wants to marry, then he, Pantagruel, sees nothing against it, but his present outfit seems, Pantagruel suggests in all modesty, less suitable for the project.

This, however, leaves Panurge with some crucial questions.

"But if you think it is not a good idea I won't do it"

"Then don't"

"And stay alone the rest of my life?"

"Then marry"

"But if she starts screwing around ... like they all do with me?"

"Don't marry, they all do"

"Aren't you overgeneralizing?"

"Marry!!!"

"Some beat you ..."

"That's what I am saying, don't start with it"

"But I am debtless, no creditor is interested in protecting me, now I am without debts I am totally uncovered"

"Indeed, then marriage is your only solution"

Now it should dawn upon us that all this is Panurge's non-verbal response to Pantagruel's non-verbal reply in the debt-discussion, that consisted of paying all Panurge's debts. Had Pantagruel now said: then make some debts again ... the book would have ended right here. Game over. As it stands, Pantagruel too proud to back down, even facing Panurge's sucking lament, as to our unspeakable fortune he will remain, we did not even reach the middle of our reading! But let us cross this most critical of passages, this narrow waist of the book's hour glass as it were, and continue:

"But if by illness or accident I cease to be able to fulfill my marital obligations, she could start cheating me, stealing from me, as we see this all around us ..."

"Yes, I warned you did I not?"

"But then how to get legal descendency?"

"Then there's no other way, take a wife", Pantagruel replies, set to employ heavier means to end this.

And Panurge succeeds in pulling all hero-friends of Panurge in his self-designed deadlock of marital advice: brother Jean, Epistemon and Eusthenes not excepted. There turns out to be no way back until the end of the last book, published posthumously. The entire world of scholarship, devotion, devote scholarship, occultism, occult scholarship, spiritism, spiritist scholarship, oracle language, oracle explication, to mention just the start of it, will be tried in the next two hundred thirteen and a half pages, empty pages, prefaces, and digressions not counted.

The problem fuelling the quest could of course have been another one. Any quest would do, but, since holy grail went out of fashion, Panurge deserves contemporary man's gratitude for selecting one that is as pressing in our times as it was in his.

Let me, by way of summarizing introduction, say that we shall visit a host of experts who all produce the same diagnosis: if he marries, Panurge will no doubt get A) cuckolded B) beaten C) robbed.

Bert's Concise Panurgian Advice Service Guide

|

Legend: * : Recommended ** : Worth a detour *** : Worth a special visit |

* Homeric and Virgilian lotteries: take an arbitrary page of one of these fine authors' books and ponder what the writing there could mean to you and your problem. Panurge resists. He prefers to throw dice. A compromise is forged: the page shall be selected by dice. Pantagruel reads the page and has no doubt: Panurge, if he marries, will be A) cuckolded B) beaten C) robbed. Panurge is quite sure the words mean the exact opposite. Stalemate. But is it not a golden chance for Pantagruel to let Panurge head for marriage? Rabelais does not explain why, but Pantagruel now developed the actual ambition to talk Panurge out of it. The heroes decide to try another method.

* The explanation of dreams. It results in a similar stalemate

* A sibylle of Panzoust shakes eight leaves from a tree, writes something on them, and throws them in the wind again. Then enters her hut, after, on the threshold, bending forward inward, lifting her skirts to allow a view on her impressive back side to our heroes, who quickly catch the leaves, and read ... which again yields the familiar stalemate interpretation differences.

*** Council of a deaf mute. As my three stars indicate, this man is amply worth your day. On the climax of a conversation in sign language that would make any righteous comic strip artist stand in awe, Panurge bursts in anger because the man becomes agitated and violent. To his friends it is clear this is due to the man's desperation in trying to make clear that Panurge will actually marry and then be A) cuckolded B) beaten C) robbed. Panurge feels unable to refute the message or even to disqualify the messenger. In utter despair he asks his friends to believe the clause that he is going to marry, but that nobody will ever be as happy with his women and horses as he knows himself to be predestined.

We now all prepare for marriage, but no, Panurge, despite his now unmovable conviction turns out to be keen indeed on continuing the round of advise. Which makes us end up at the indeed invaluable ...

*** ... Raminagrobis, in the following way: sixty three and a three quarters of shiploads of book wisdom leads our heroes to the conclusion that light on the issue should be shed by an old dying poet. Soon the kingdom's spies report they have found one, Raminagrobis. Like the sybil and the deaf mute, Raminagrobis gratefully receives the precious gifts, then writes a little but telling poem. But we never reach the stage of its interpretation: Raminagrobis confides to the company that he just chased away a huge crowd of zealots of all religious specifications, fighting among themselves to be the first offering him the terminal care appropriate to his standing and condition, for a competitive fee. Panurge - I leave it to you as the reader of this, to suspect, or not to suspect, theatre - gets haunted by terrible fears of the devils that must have been involved in this, and flees in a burst every onlooker felt sure would make him sprawl but he managed and disappeared behind the horizon.

Epistemon himself. Next. Panurge privately consults his intimate friend Epistemon. The cheapest consultation thus far: no invoices among friends. But all friends, Epistemon included, now have a hidden agenda: talk Panurge out of his marriage wishes. Epistemon advises Panurge to shift back to his old outfit, but Panurge replies that his oath to the holy saint I-forgot-his-name requires him to wear this rough wrapping, cap and spectacles dangling down from it and the flea-earring included, until he solved his problem and decided to marry, or not. That prompts Epistemon to pass the ball on and recommend a visit to ...

** Herr Trippa. Panurge seems not too impressed by this specialist in, among others, astrology, geomancy, cheiromancy, metopomancy, catoptromancy. Herr Trippa is known once to have been honoured with an audience to the king, while his well formed wife got, to her own delight, a thorough treatment outside on the stairs by the court's lackeys, which subsequently became known to the entire country except this very Herr Trippa who now receives Panurge, analyzing the visitor's face in a split second (physiomancy) and concluding: such a person, if in a marriage, will get cuckolded, beaten and robbed by his wife.

This prompts Panurge to start muckraking like a possessed: you look at yourself Trippa, you old fool!! Dirty daft dredger! et. cæt. Not in the least upset, in full concentration, Herr Trippa applies another seven hundred and twenty one methods, a neat and careful selection of his full range of treatments. All of them have the same treble result.

A climax is his application of onomatomancy (diagnose basis on somebody's name). "What is your name?". "Chewturd!!" Panurge shouts. To no avail. The outcome is the same. Panurge's excitement now rises to the level of calling Herr Trippa a heretic, black craftsman and magician of the Antichrist. Depressed we return home.

* Brother Jean himself. I am aware the expectations of the reader could not run higher than on this point. However, Rabelais himself collapses in this meeting between the two real giants of the book. On the one hand, Rabelais must have felt brother Jean could not be left out of the round of advice, on the other hand, this should not end the book. Even brother Jean seems to have understood his role here would have to be subtle and limited. To avoid getting cuckolded he recommends Panurge to make maximum use of his genitals, but concedes - under heavy protests of Panurge - that the procession of his age might come in the way. The B-option is, he holds, to wear Hans Cavel's ring. In a dream, the devil put a ring on Hans Cavel's middle finger that would prevent his wife cuckolding him as long as he would wear it. The ring was painfully tight so Hans Cavel woke up. With the finger in question in his wife's cunt.

*** A meeting of a theologian, a medical doctor and a lawyer, who are called upon to deal resp. with soul, body and property, which together cover Everything, but ... a philosopher, someone who can answer all questions professionally, is seen as a useful extra. Professor Wordspinner declares himself capable and willing. He joins in.

This leads to what is the absolute lowest ebb in the entire marriage consultation round. For our heroes, that is, for us readers the opposite holds, I give 3 stars. Though the medical doctor manages to say some things worth considering - after all, the author exercises the same trade - now all heroes do have genuine compassion with Panurge's depression and know something should be done on short notice.

They decide to get really serious and go for ...

* The advice of a fool. This turns out to be a procedure with a firm foundation in authoritative literature and tradition. The fool Triboulet makes some - what are thought to be - statements. Pantagruel opines it conforms the threefold undesirable outcome of a marriage, but Panurge disagrees.

But Triboulet said something about a bottle as well, and Panurge firmly believes this means the faraway Oracle of the Bottle should be consulted. It seems there are people who know where it is. It is called Lanternland or something.

Pantagruel, the King's son, is prepared to go, but should ask the consent of his father first. The entire rest, in total excitation, is ready to go at once.

Not much later a fleet is being prepared and Book III ends with a hymn to the magnificent properties and performance of a herb strikingly resembling hemp, though consistently called pantagruelion. It is sung during the dropping of shiploads, both in raw and in processed form, at the quay, to form a crucial and substantial part of the fleets victuals, in preparation for the departure to Lanternland. So, though they do accumulate, in impeccable scholarly style, quoting all classics and beyond, some grass under their feet, they board ship for the long trip in ...

Book IV The Quest Takes The Sea

Off to Lanternland, the seat of the Holy Oracle of the Bottle. The Portuguese, the heroes know, are in the habit to pass Cape the Good Hope and then head East, but Xenomanes, the "great voyager and traveller over dangerous routes", opts for passing between America and the North Pole, the first mentioning of the North West Passage in history!

Xenomanes, a redoubtable and experienced sailor, decides he knows the map well enough to leave it home for father king Gargantua to follow the journey.

Before - two hundred and thirty pages later - we sight Lanternland, we encounter a host of island communities instructively resembling our own proud worlds of politics, war, devotion and scholarship, a remarkable side effect of the journey that makes our heroes forget all marriage problems and naturally prompts them to an undaunted, expert and learned philosophizing.

Bert's Concise Panurgian

North West Passage

Island

Guide

|

Legend: * : Recommended ** : Worth a detour *** : Worth a special visit |

* Medamothi

* Ennasin

* Cheli

*** Clerk Island (French: Procuration). Here our heroes encounter judicial court sharks and loan ushers (chiquanoux), the latter masochistic characters who monetize their sexual preference by having themselves sent to someone to hand over a writ, which they then do under ejection of extensive insults.

This serves the purpose to excite the receiver in such a way that the chiquanous receives, to his satisfaction, a decent beating, after which the customer tends to pay his debts and some damages on top of it.

Brother Jean has a go on one of them, but his fun is over before his chiquanous lost his appetite. The philosophical problem raised by our heroes is how to negotiate with these chiquanoux and how to teach them a lesson. By threatening not to beat them? The entire theory of cost and revenue, of reward and punishment, needs fundamental scholarly reconsideration. But some traditional stories of the island suggest that when you do not despond and continue your beating long enough, in the bitter end the chicanous will stop enjoying it.

Thohu en Bohu,

Nargues en Zargues

Enig en Ewig

*** Teneliabin and Geneliabin, after which Panurge, in a terrible storm eloquently grows in his magnificent role of scaredy-cat, later retaliating the well-deserved taunt with: "What are you talking about, I am afraid of nothing. Only of danger!"

*** The islands of the Longlivers, where a discussion of heroism results in an unlikely comparison, by Pantagruel, of Jesus with the Greek God Pan (elsewhere not exactly venerated as a champion of Christian civilization). But Pantagruel's metaphor touches the company to the point of tears, and they sit for a while in silence, with lumps in their throats.

** Stealth Island (Tapinois), of King Quaresmeprenant (fast - the religious ritual), is, the guide Xenomanes tells the company, too far off route for value, mainly because of its poor gastronomy. However, Xenomanes reaches new heights in his eloquent descriptions of the repelling character, appearance and deeds of this king.

*** Island of the Wild (Farouche). It is densely populated with extremely aggressive sausages, andouilles, to be precise. They are battle hardened, for they acquired war experience fighing their arch enemies on the island the heroes just visited, Stealth Island (Tapinois) so here our heroes immediately sense a noble case. They enter in coalition with the Farouchians. Brother Jean attacks Tapinois with Pantagruel's fleet manned by an army of cooks which gets unsuspected air support from a flying swine dropping tons of mustard over the enemy. Needless to say: Tapinois ever since is uninhabited.

* Island of Ruach. (means "wind" but also something like "soul"). One feeds on wind only and defecation is limited to farting.

*** Papimania Island, where the Pope is worshipped. The holiest writs are the papal decrees, only then comes the Bible. However, the food is excellent, drinking is good, service is done by attractive girls and precious metals are seen all around.

* The domain of Mr. Gaster (Stomach). Mr. Gaster turns out to be the inventor, and license holder of about all trades and techniques, war not excepted.

* The island of Chaneph (Hypocritia), where our heroes refrain from contact with the very religious local population but go at table to exchange to available information about them. This goes with ample and good food, for, it is argued, proven and founded in all classical literature of importance: with an empty stomach your saliva turns into a poisonous substance. A complete list of all poisonous animals is made up. Brother Jean's mouth asks from under his long nose in which category of this list we should put Panurge's future wife.

That's a hard and unsuspected one, for we had not discussed this issue since we took to the sea. Panurge vehemently protests, but others hasten to quote Euripides Andromache: man can counter all poisons except that of women. Panurge grabs this golden chance to raise his role to new heights and starts screaming like a sucking-piglet.

About one subject Rabelais stays silent like a corpse: who does, and who does not realize that Panurge's entire flea act is a scam in the first place? Brother Jean surely. Perhaps the only one.

* Ganabin Island (Thug Island). Brother Jean proposes to rob it., but Pantagruel somehow feels uncomfortable. Think of it: Pantagruel!! The compromise is a decent artillery volley in passing, the noise and smoke of which makes Panurge dirty himself malodorously. When the smoke starts thinning again, he claims not to have feared at all, yes, all the way having remained brave enough, by God!, to eat all flies you find in Paris bakery products.

Quite unexpectedly book IV ends, but, to our utmost relief, it is continued in

Book V The Quest Takes The Sea (Continued, published - wisely - posthumous)

*** Bell Island. This is the habitat of a wide range of birds like monkjays, priestjays, bisshop jays and even a popejay. They do not breed but arrive from neigbouring islands like Nobread, and Toomanyofyou. Once on Clock Island, they are put into cages with a clock on top. When you ring the bell, they will start to sing. The required alimentary supplies used to come from all over Europe, but recently the North ceased its deliveries due to what - they called - "Reformation".

Tool Island. Uninhabited, covered with tools.

Cassade Island: Habitat of devils dwelling in cube shaped houses made of bone, with numbers and dots on all sides.

** An Island with the curious name of Little Side Door. Closely allied to Clerk Island. Archduke Claw of the Hairy Cats is the President of the High Court which lets the small ones pay and the big ones go.

The Island of the Ignoramusses (the We-Don't-Knows). You find a press at every corner. All kinds of grapes are pressed until they are reduced to mere crumbs of leather. All presses have names, strange ones: Declaration, Provisional Assessment, Definitive Assessment, Levy, Additional Assessment, etc.

Near that island lies the other one, aptly called Outre. among its dwellers, obesity and liposuction are so common that the sounds of explosions of new fat bursting out of old liposuction scars are heard all day.

*** Kingdom of the Quintessence or Entelechy Island. These are high brow folks. At the beach landing the discussion is of such an elevated level that Panurge pesters an unprecedented expression of fear out: "No man from Beauce would now be unwelcome to plug my ass with a cart of hay"

The other heroes, normally far from shy of a classical quotation or thirteen at least per single passing subject, grab their courage together to address these intellectuals: "please forgive us, we are only peasants!". There is some wavering among the hosts, but finally they are allowed on the Island. Relief.

The queen of Quintessence, over eighteen hundred years old, but a slender, impeccably dressed beauty, does not know any common words. She has comprehensive knowledge and cures diseases. Her lunch normally consists of categories, abstractions and generalizations. For dinner she does take some meat, but this is chewed for her and then inserted through a golden tube. There is a rumour that at toilet visits she does not land on the hardware but somehow, unsustained, keeps hovering slightly over it in the air.

Odes

* Sandal Island, seat of the Order of the Trembling Brothers.

Satin Island. Here the entire world is on display. On cloth. Tissue. A huge, if not gigantic educative gallery designed according to the direction of Mr. Hearsay. Hearsay's mouth reaches from ear to ear, his tongue ends in seven independently controllable strips that can speak every language, despite the tragedy of his birth that kept him blind and deaf.

Finally we sight the Island of the Oracle of the Bottle. We all at once remember the almost forgotten theme the book assumed after Panurge got his debts paid by Pantagruel. Even Panurge had become more talkative, but now he swiftly reassumes his star role.

* Lanternland, where the Oracle of the Bottle, the aim of the heroes, is said to be located. I give one star, even though this is a bit generous, but what can I do: for more than half of the book now this is the aim of the voyage.

The book is now at page seven hundred twenty two, has made the most unpredictable of turns and moves, the author had not burnt any option for how to end it, and clearly in this total freedom chose for a slightly boring one to make the ending not too sad for the reader, and we're grateful.

The oracle says: "Trink". Priestess Bacbuc explains this, using a silver book that has no text but is a decanter filled with wine.

Panurge is granted a sip and sings out his marriage plans in impeccable rhyme. His friends rhyme to each other in despair that now he lost his wits completely.

Back

to the ships

Back home

END

TRINK

Introduction to Book 3.

Indefatigably, throughout the book, Rabelais keeps advertising spiritual consumptions. Which in particular? There is white Anjou, with its star role in the brilliant Lethal Urine Inundation attack. But what the true spiritual consumptions are, Rabelais explains in the introduction to book III. There, he compares his writing activities with what Diogenes did during the excited preparation of the city of Corinth for an expected upcoming siege and attack on their town. Diogenes took to a hill slope visible from town. He took his house, a barrel, with him. There, he began to roll the barrel up and down hill: "to share the general feeling of doing pressing things".

Reading, Rabelais holds, is like drinking spirits, but these are very special spirits: firstly, while drinking they do not disappear. The stock is infinite. Secondly, the reader can enjoy and never has to fear the end of it. So there are no worries at all, the spirit out of this bottle keeps flowing.

Ask the monks, they know: they invented the breviary recitation bottle, which looks like the Bible as two drops of gin!