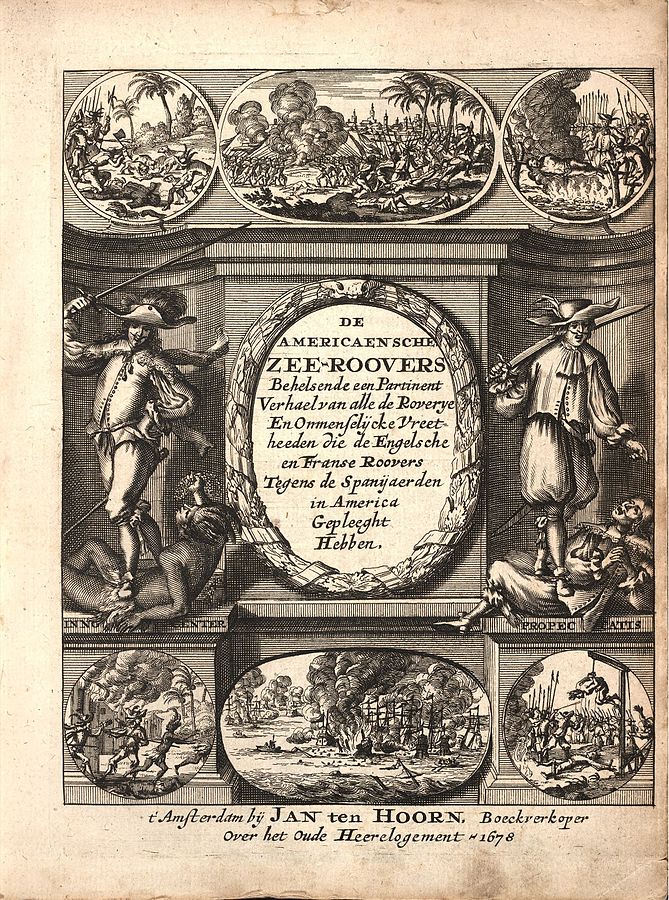

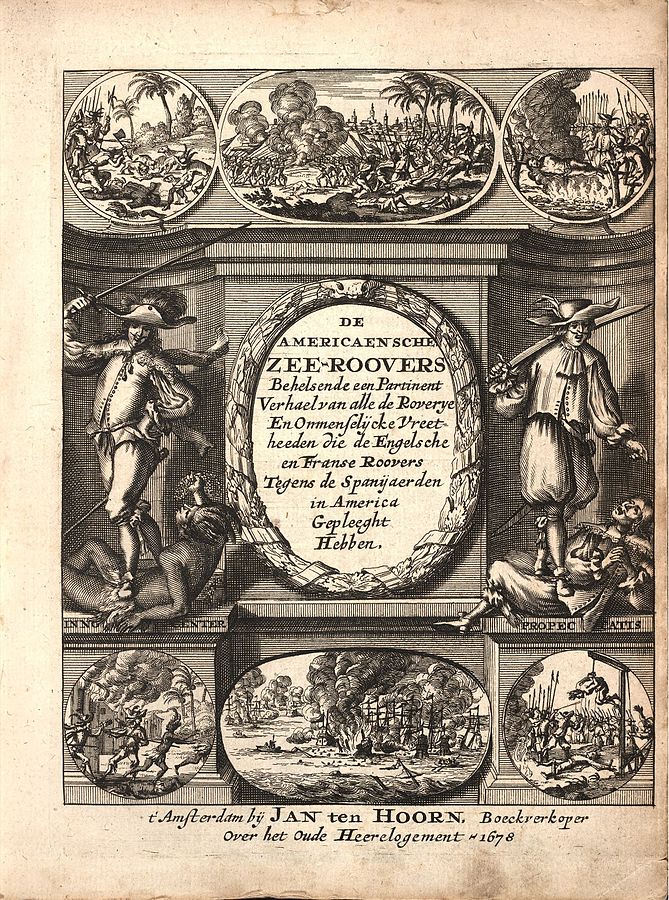

... "The American PIRATES. About a strong story of all robberies and inhuman cruelties committed by the English and French pirates against the Spaniards in America" ...

| Lingeblog Home |

| Previous |

| Next |

| Dutch |

Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin, slave, pirate, surgeon

... "The

American PIRATES. About a strong story of all robberies and inhuman cruelties

committed by the English and French pirates against the Spaniards in America" ...

In 1666, Exquemelin left le Havre for Tortuga (Caraïbbean) as a sailor for the French West Indian Company. The island gets occupied, conquered is seems, from the Spaniards. Who came up with that idea? May be the captain, but once such a ship leaves the harbour of departure, human relations develop that few would have anticipated. When later, after the occupation of Tortuga, this Company manages to install a company administration again, it sells too much to its own countrymen on irretrievable credit. Then, is is ordered by the Company to liquidate by selling all that remains for cash. We are not told how Exquemelin came to be considered as company property but anyway, the Island's deputy governor offered twenty or thirty pesetas for Exquemelin, and so the Frenchman entered into the slavery of another Frenchman, whereby the yield got cashed in, it seems, by the West Indian Company.

Exquemelin neither complains nor is he amused about these proceedings. He restricts himself to reporting the events themselves, and we are grateful for such saves us useless reading. He got treated so badly that he lost his health.

Well, you see, shit happens.

But then luck came: Exquemelin getsin danger to die, a misfurtune to his owner, who swiftly sold with a loss to a doctor whose medical knowledge led him to believe he could still fetch something useful out of poor Exquemelin.

And not only did the doctor succeed to keep Exquemelin alive and thus maintain him as a useful item of his wherewithal , he treated him well and finally sold Exquemelin back to himself. The price meant a good profit, but the sale was on credit. Exquemelin joined pirates using what he learned of the medical expertise of his last owner to pose as a "wound healer" and vaguely suggests that later he loyally returned to pay his "debt".

Of course we shall never know if there's any truth in this or anything else.

God does not enter Exquemelin's story until firmly in the middle of his chronicle, where a (white) worker is thoroughly tortured to death by his boss en his last words are: "May at your death God make you suffer as you made me now", a request that, especially in these circles, should be easily honourable by the Almighty without much of His Divine interference, but interfere He did, Exquemelin reports: "He send him an evil spirit that is haunting him since."

Once at sea, order, morality, property rights and chain of command as they are established while preparing the trip in a European harbour quickly and spontaneously fade to evolve in a balance of power determined by the sea. That is: you are what you do on board, who needs you, who can use you. What, at sea, is to be bewared of? Without neglecting storms, robbers and enemies, every sound sailor in the first place bewares of his fellows. But the golden chances lie exactly there as well: any youngster with brains sufficiently above average to advise the hulks around him to their satisfaction in no time has the captain overboard and taken his hut with his pockets filled.

What does this mean to the behaviour of the ship as a whole? It will follow an iron logic: if a stronger ship is encountered, one hastily sails away to avoid being robbed, and if it is smaller, one sets all sails to catch up and rob it. Fellow nationals and nationals of nations not in war have a chance to a friendlier treatment in terms of a forced "donation", others should not count on survival unless their ship is judged good enough to seize en they are needed as sailors. In the situation where neither side feels itself superior, the flags are lowered and delegations are rowed over to discuss the trade of the available cargo.

As far as the peoples overseas are concerned, the term "trade" also includes many kinds of creative and violent forms of property acquisition such as robbery, blackmail and war. Trade in the contemporary sense of bargaining an exchange of goods is quite low on the list of preferable solutions, rather a method of last resort.

We have not yet dealt with pirate culture specifically, but only with the general culture of intercontinental shipping. What exactly specifies the pirate? If there is such a thing, is a subtle matter. The distinction between ships sent out by citizens of nations, and ships ran by outlaws is often thought to be the appropriate one, but in practice things rarely are that clear: pirates can be loyal to their nation, though often are not. Pirates regularly get endowed by nations (kings) with "pirate letters" that give them the "right" to commit piracy to such a nation's enemies - even flying an official flag to communicate this, which during approaches by navy ships of the issuing government was an expedient to avoid unnecessary exchange of fire. And a government can issue such letters to pirate ships run by foreign nationals, which can render, say, a French pirate, perhaps at odds with his own nation, loyal to England. These types of chartered highway-men-at-sea tended to judge themselves of a morally higher standing than pirates and call themselves "privateers".

On the dry soil of the European home lands this was, by the way, no different. When going to war, the larger part of some king's army would consist of foreign mercenaries, not hired individually but as a readily trained set of units hired out by a commander running his service as a commercial enterprise. Such mercenary units could, after war might have brought them into disarray, easily end up as bands of robbers, until, for instance, swept up by some local general building up another army.

But! When Exquemelin describes how in a pirate port a ship gets prepared, and men and goods enter the operation through contract and agreement, one smells the specific piracy-edge of an operation: sea culture does not wait to come over the crew once at sea, but already reigns the preparatory negotiations. While in an official national port sailors get hired by a boss, pirate sailors negotiate their role as private business partners in the operation. In sea trade operations monitored by official governments, sailors and soldiers are hired, though when at sea the death toll rises, as it usually does, survival needs often makes the distinction between these ranks fade. In a pirate port, all interested in negotiating a participation are sailors-fighters and usually arrive at the scene with their own weapons and gear.

The contract of the sailor-soldier-pirate does not state a wage but defines how the shares in the booty will be determined. There are some wage-owners though, like the carpenter and the surgeon ("wound-healer"). The booty will be divided net of compensations for wounds, lost limbs and eyes, that all have fixed tariffs. The rest is divided in personal shares, though not everybody's share is the same. The ship's owner, be he the captain himself or not, receives a share as well. An elaborate ritual is put in place to prevent cheating during the division into shares. It is a good thing we are all Christians so can swear all these firm commitments by oath on the bible, whereby we seem refreshingly disinterested in the distinctions between the Christian denominations. Who nevertheless gets caught cheating is probably dead. If he survives he gets blacklisted in the entire pirate community. To get lower while still on earth, seems impossible.

As usual among most European sailors at the time, those debarking from pirate ships with their valuables acquired in such dangerous circumstances seem to need them chiefly to impress the harbour town public by spending them conspicuously and lavishly, finishing them off as quickly as possible, and return to the sea.

______

In which I have endeavoured not to give away any of the spicy and entertaining details this instructive chronicle abounds with.